Business Model Exploration

Identifying and testing different ways to create, deliver, and capture value in tech startup business.

Exploring business models is a critical phase for startups and established companies looking to innovate and adapt in a dynamic market environment. A business model defines how a company creates, delivers, and captures value. This process involves identifying key components such as target customer segments, value propositions, channels, customer relationships, revenue streams, key resources, key activities, key partnerships, and cost structures.

One effective approach to business model exploration is using the Business Model Canvas, a strategic management tool that provides a visual framework for describing, analyzing, and designing business models. This tool helps entrepreneurs and managers systematically understand, plan, and implement changes to their business models.

For instance, a company might explore various revenue models such as subscription-based, freemium, or pay-per-use to determine which aligns best with their customer base and market conditions. Additionally, innovative business models like platform models, where the company acts as an intermediary between different user groups (e.g., Uber, Airbnb), can offer new avenues for growth and profitability.

In today's fast-paced market, continuous business model innovation is essential. Companies must regularly revisit and refine their models to stay competitive, meet evolving customer needs, and leverage new technologies.

Two key questions entrepreneurs must ask themselves during the early stages of their startup are:

- Why now? Why hasn't this problem been solved by anyone else previously?

- What secular trends or technology waves might provide the venture with enough momentum to get off the ground and, over time, become a massive success?

To answer these questions, founders must understand the current context their startup will operate in and the precise value they plan to provide to their ideal target customer.

Determining who it is you are providing value for and what value you are providing to them — the customer value proposition — is one of the essential components of a strong startup business model. Different companies find different ways to provide value. For example, companies like Amazon use a disintermediation strategy by cutting out the intermediary to make a product or service more accessible. Other times, a compelling interface or intermediary service can be attractive to consumers as a portal to discover new products and services.

When thinking about your target customer, in what ways might you develop a clear understanding of your users and their needs? Do you know them well enough to help develop a solution to a problem they might have?

- What type of customer discovery processes have you used to better understand the requirements of your target customer(s)?

- Which ones have been more successful and which ones have been less successful?

- Have you ever felt as if you focus too much on customer feedback and should simply make a conceptual leap about how the future would unfold? Henry Ford, the creator of the Ford automobile, once quipped that if he had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.

Idea to MVP

MVP stands for "Minimum Viable Product". It's a concept from the Lean Startup methodology, which emphasizes the importance of learning in new product development. An MVP is the simplest version of a product that can be released to market with enough features to attract early adopter customers and validate a product idea early in the product development cycle.

Here are the key aspects of an MVP:

- Core Features: An MVP includes only the essential features that address the primary needs of its target customers, allowing them to accomplish their goals. This focus helps to avoid overengineering and unnecessary features.

- Feedback: The main purpose of an MVP is to gather feedback from users quickly. This feedback is crucial for learning what works and what doesn’t, enabling the product team to make informed decisions about how to evolve the product.

- Iterative Development: Based on the feedback, the product is refined, and additional features are developed. The MVP is not the final product; rather, it’s the starting point for a cycle of testing and improvement.

- Resource Efficiency: Developing an MVP requires fewer resources than a full-fledged product, making it a cost-effective strategy for startups and companies testing new ideas.

- Time to Market: Launching an MVP allows the product to reach the market sooner. This can be a significant advantage in fast-moving industries, providing a first-mover advantage or simply the ability to begin building a customer base early.

By focusing on an MVP, companies can minimize their risk and investment while maximizing learning about customer needs and market dynamics.

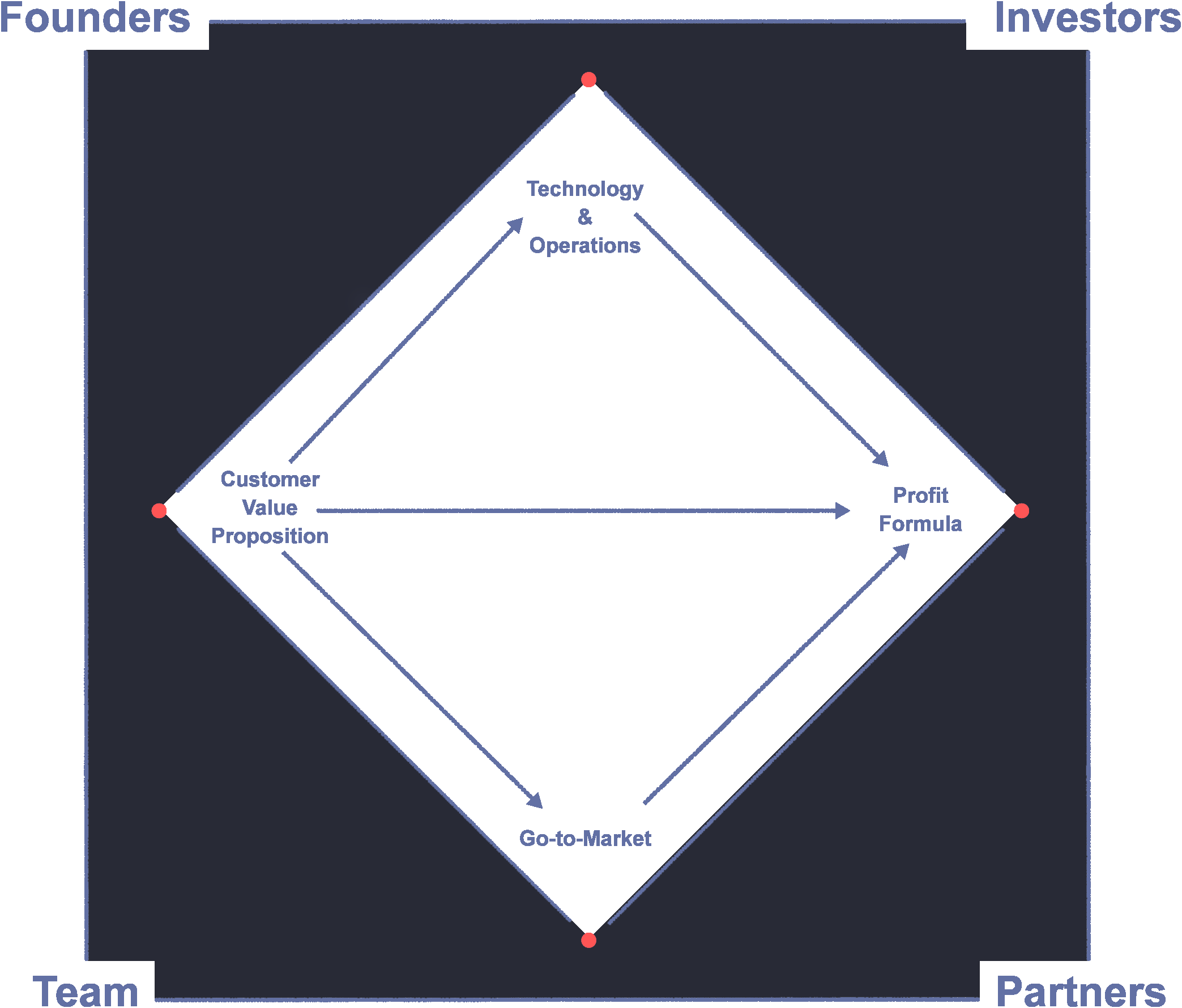

Diamond-Square Framework

After testing for your value proposition and confirming there is interest from users in your MVP, you want to understand if you build a more sophisticated product than your current rudimentary MVP design, how would you acquire customers? How would you let people know the product exists? How would you make the product easy for your customers to access? In other words - how to distribute it (go-to-market plan)?

After initial exploration into how to distribute the product and your go-to-market plan, you can begin to think through how you would make money from your service — how much would you charge, and who would you charge? These questions point to the next component of the startup business model that you have to wrestle with: what would your profit formula be?

You continue to investigate additional customer segments as you work on building up your product beyond the simple MVP you had created. To achieve this, you have to figure out how to produce the product, and make money along the way.

To align all elements of the startup business model is to ensure that you understand how each element impacts the others, and to set them up so that they support each other in creating the most value possible for the customer and the company.

Now, let’s focus in on the first four components of the startup business model, which represent the firm’s core operating design, and think about how we could test these components to expose any potential for misalignment.

To have something to work with, let's review the four internal components for the company Plastiq that provides a payment automation platform designed for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Plastiq enables businesses to make and receive payments using credit cards for transactions that typically require checks or bank transfers. This allows companies to pay bills, rent, and other expenses using their credit cards, even if the vendors do not traditionally accept card payments.

| Customer Value Proposition (CVP) | Allow individual consumers to pay for large ticket items, using their credit card. |

| Go-to-Market (GTM) | Approach universities directly and integrate with their tuition acceptance process to incorporate credit cards. |

| Profit Formula (PF) | Charge 2-2.5% on a transaction from the consumer and, after paying off everyone, keep 40 basis points (0.4%) per transaction. |

| Technology and Operations (T&O) | A website that allows consumers to enter their credit card information and identify which merchant they want to purchase with. Then, Plastiq would onboard those merchants one at a time. |

Do you see any potential for misalignment? What other tests may they want to run to probe at this question of alignment? To test for CVP, they already used a simple MVP to validate their hypotheses within the private school space.

To uncover misalignment, it is critical to run tests within each part of the business model and then analyze how the results implicate the other components. Here are some examples of tests the Plastiq team could run within each component of their business model:

| Customer Value Proposition (CVP) | - A survey to validate if individuals would be interested in paying for large items with a credit card. In particular, survey which types of customers might react more positively to the offering. - A small pilot, like they ran at the school in Canada, to see if, provided the option, customers would choose to pay their tuition with a credit card. |

| Go-to-Market (GTM) | - Interviews with customers who paid via credit card in their pilot to ask them if there was any friction when learning about the option and administering the payment. - A survey with customers to ask them which is their preferred method to learn about new payment options. |

| Profit Formula (PF) | - A pilot where they charge the transaction fee and see if customers are willing to pay the fee at the current rate. - A pilot at a different type of location where the customers pay for a different expensive item to see if people would still be willing to pay the fee with slightly larger or smaller payments. |

| Technology and Operations (T&O) | - Build an MVP website that automates the merchant onboarding process and see if it works for a small group of merchants. - Interview customers about their experience on the website and if they felt it was secure. |

Network Effects and Flywheels

As you think about designing your startup business model, keep in mind the quality of that model. You're not just trying to start any business. You're trying to create a business that is profitable, sustainable, and valuable. Profitable business models typically have a unique value proposition and customers who are willing to pay for that value at a level that generates substantial profit margins.

Convincing customers to pay for the value you're creating can be influenced by an economics concept that often characterizes the most valuable business models on earth: network effects. Network effects refer to any situation in which the value of your product or service depends on the number of buyers or users. Typically, the greater the number of buyers or users, the greater the value created by the offer.

Many popular internet companies have strong network effects, such as Uber, where the value to a user is influenced by the number of drivers there are in the

network, or LinkedIn, where the value to a professional user is influenced by the number of other professionals there are in the network.

Startups with business models that contain strong network effects often grow

rapidly, and build out what is known as a positive flywheel. A positive flywheel occurs when a well-designed and aligned startup business model gets going. It self-reinforces and feeds upon itself, building momentum every step of the way with little or no friction as causal relationships in the business model drive follow-on success.

Amazon's founder, Jeff Bezos, famously sketched on a napkin his company's "virtuous cycle" or positive flywheel that begins with a great customer experience and low prices, and then leads to a lot of customer traffic, which allows Amazon to attract third-party sellers who offer a broad selection of items at lower prices, further reinforcing their flywheel.

If you can design a strong network effect and a positive flywheel into your business model, you're more likely to achieve a sustainable, profitable, valuable business. Because once you get going, your momentum generates more positive value going forward.

Let’s consider Plastiq’s network effects. On the consumer side, there isn’t any additional value to having more consumers on Plastiq, but there is more value to having more merchants because then consumers can use Plastiq at more of the places they make purchases. On the merchant side, there is additional value to merchants to have more consumers on Plastiq so that they can use Plastiq to purchase from them and there is also more value to have other merchants using Plastiq because it drives more consumers to use Plastiq.

Network Effect Tension

Plastiq was fortunate to have strong network effects and self-reinforcing flywheels. But this is not always the case, especially in a two-sided market where you are serving two customer groups, such as customers and merchants. An example of this occurred in the early days of the company ClassPass, previously known as Classtivity. Classtivity wanted to create an application that would make it easier for users to find fitness classes near them. One business model they came up with was called the “Passport,” which bundled complimentary classes for newcomers at various workout studios. The cost of the Passport would be $49 for 20 fitness “tickets” to claim at the studios. Users could only purchase this promotion once and had to use it in a 30-day window. By bundling free classes, Classtivity would receive 100% of the profits, and users could explore new workout venues around their city. It also made it easier for users to find the best classes in their city curated in the Classtivity platform. But, Classtivity had another customer to deliver value to, the fitness studios. They promised the studios that if they participated, new people would come into their studios and become loyal followers thanks to Passport.

While it was clear that having more fitness studios on the Classtivity platform created more value for users who enjoyed the variety, the studios would only realize value if the users decided to sign up for a membership after trying the first free class with the Passport. For the studios, it would be advantageous for them to have more users on the Passport but fewer studios, making it more likely for users to sign up with them and purchase an ongoing studio membership. This tension with the network effects, and the inherent friction in the business model, prevented a flywheel from occurring and ultimately resulted in the model failing because users wanted to keep going to new, discounted classes instead of committing to a studio. The result was new customers would visit the studios only to claim their free class and then never return. This misalignment forced Classtivity to pivot to a subscription-based model, which still provided variety to the customers, but the studios were compensated and guaranteed recurring revenue.

Wrap Up

Now that we know the components of a business model, in the next article, we will characterize and analyze different business models.

For further reading and detailed examples, you can explore resources such as Strategyzer's Business Model Canvas and books like Business Model Generation.