Case Study: Seat Belts and the Five Factors of Innovations

Implement: Communicate and Structure for Success - Overcoming Developer and User Bias

Learning Objectives:

- Understand factors affecting the likelihood of innovation/product adoption

American car manufacturers began to offer seat belts as a safety feature in the 1950s. In 1968, Congress passed a law requiring that they be installed.

Where do you think seat belts fit in the preceding 2 by 2 framework?

- Quick Wins

- Low ROI

- High ROI

- Strategic

Seat belts may seem like an easy quick win or a high-ROI innovation today—with great benefits to the safety of drivers, and minimal change required in their driving habits overall—but for American drivers in the middle to late 20th century, they fit more in the Strategic quadrant. The behavior change required was significant.

Even though seat belts became standard in all American-manufactured cars in the late 1960s, fewer than 15% of Americans were using them by 1983.

As individual states began to pass laws in the 1980s requiring drivers to wear seat belts, there was still resistance from many drivers who didn’t want to be told what to do. One wrote in 1987, “In this country, saving freedom is more important than trying to regulate lives through legislation.”

In the United States today, both seat belts and seat-belt laws are widely accepted.

The road to widespread compliance with seatbelts was long. In the 1980s, the United States government left regulation to the states. But few were willing to implement unpopular restrictions.

The issue was different for children, however. By 1985, many states had child passenger laws, requiring most children under a certain age to be restrained in car seats. While adults bristled at being told how to be safe, few could reasonably object to the idea of protecting children.

These laws served two purposes beyond protecting children from harm. First, a younger generation was raised using restraints and seatbelts as a normal behavior. Second, many of these children, as they grew older, would ask their parents why they weren't also using a seatbelt. You know how children think. If you tell them to buckle their seatbelt, they will say, why do I have to do this if you won't? These interactions gradually increased many parents' psychological comfort with seatbelts.

Over time, comfort with seatbelts led to increased political acceptance for seatbelt laws in the United States. By 2019, nearly 91% of Americans were using seatbelts.

The tactic of implementing child passenger laws demonstrates the success of making an innovation personal and taking a longer strategic view of innovation. For strategic, long-haul innovations, acceptance and adoption can be measured in months or even years.

The history of seatbelt usage in the United States is also a good example of how users undervalue benefits - even the prevention of injury or death - and overestimate costs, such as personal discomfort and interference from the government in their lives. Making a full inventory of costs and benefits and adjusting your communications according to the status-quo bias can be helpful in the initial stages of introducing an innovation.

The implementation of seat belts was eventually successful as a strategic, long-haul innovation. By focusing on children (which minimized costs and maximized benefits), manufacturers gained regulatory support and psychological acceptance.

Seat belts also reflected many of the factors that celebrated 20th-century communication theorist and sociologist Everett Rogers, in his Diffusion of Innovations Theory, called the five factors of innovations.

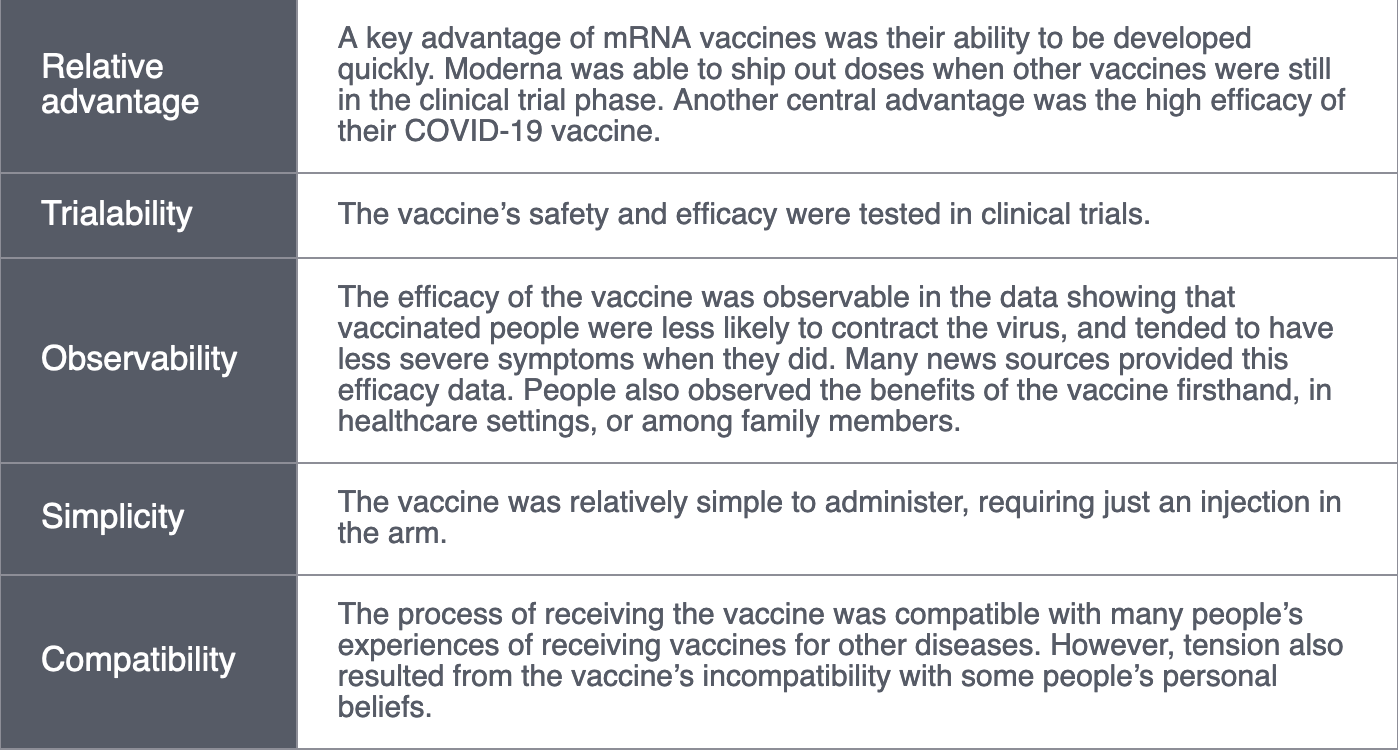

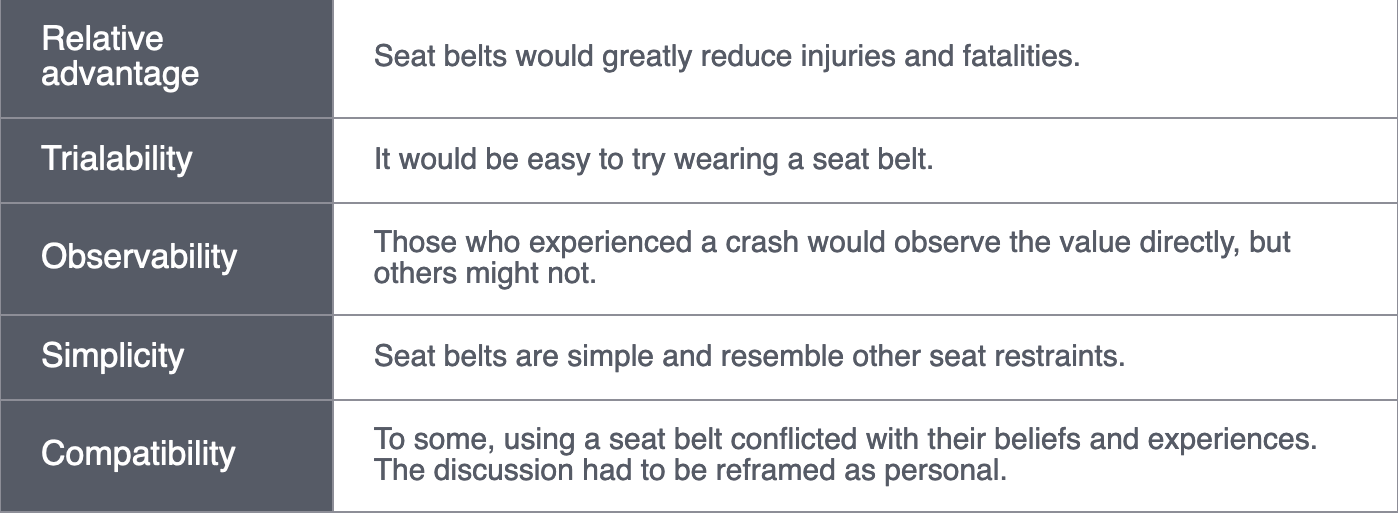

Everett Rogers’s five factors help innovators overcome the status-quo bias by minimizing costs and maximizing benefits. According to this theory, innovations with the following five factors are much more likely to be adopted:

- Relative advantage: The innovation is better (i.e., has more perceived value) than the product, service, business model, or strategy it replaces. (There are many ways an innovation can be “better,” including convenience, influence, ease of use, and price.)

- Trialability: Users can try the innovation on a limited basis.

- Observability: The innovation’s usage and impact are visible to others.

- Simplicity: The innovation is easy to understand and use.

- Compatibility: The innovation is consistent with existing values and experiences. (“Experiences” also means the user’s experiences with similar innovations. If those were negative experiences, the user may assume your innovation is similarly incompatible with their values and expectations—a reinforcement of the status-quo bias.)

In the table that follows, you can learn how seat belts reflected these factors of innovations.

Now that you know more about Everett Rogers’s five factors of innovations, let’s return to the case of Moderna.

As CEO Stéphane Bancel described, Moderna developed healthcare innovations using mRNA technology, which delivers instructions to cells to perform specific actions—the COVID-19 vaccine instructs muscles to produce harmless proteins that will trigger an immune response against the virus.

Based on what you know about the case, how do Moderna’s mRNA vaccines fulfill the five factors of innovations?

The following table presents some ways in which Moderna’s mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 fulfilled the five factors of innovation: