Clarify Through Observation

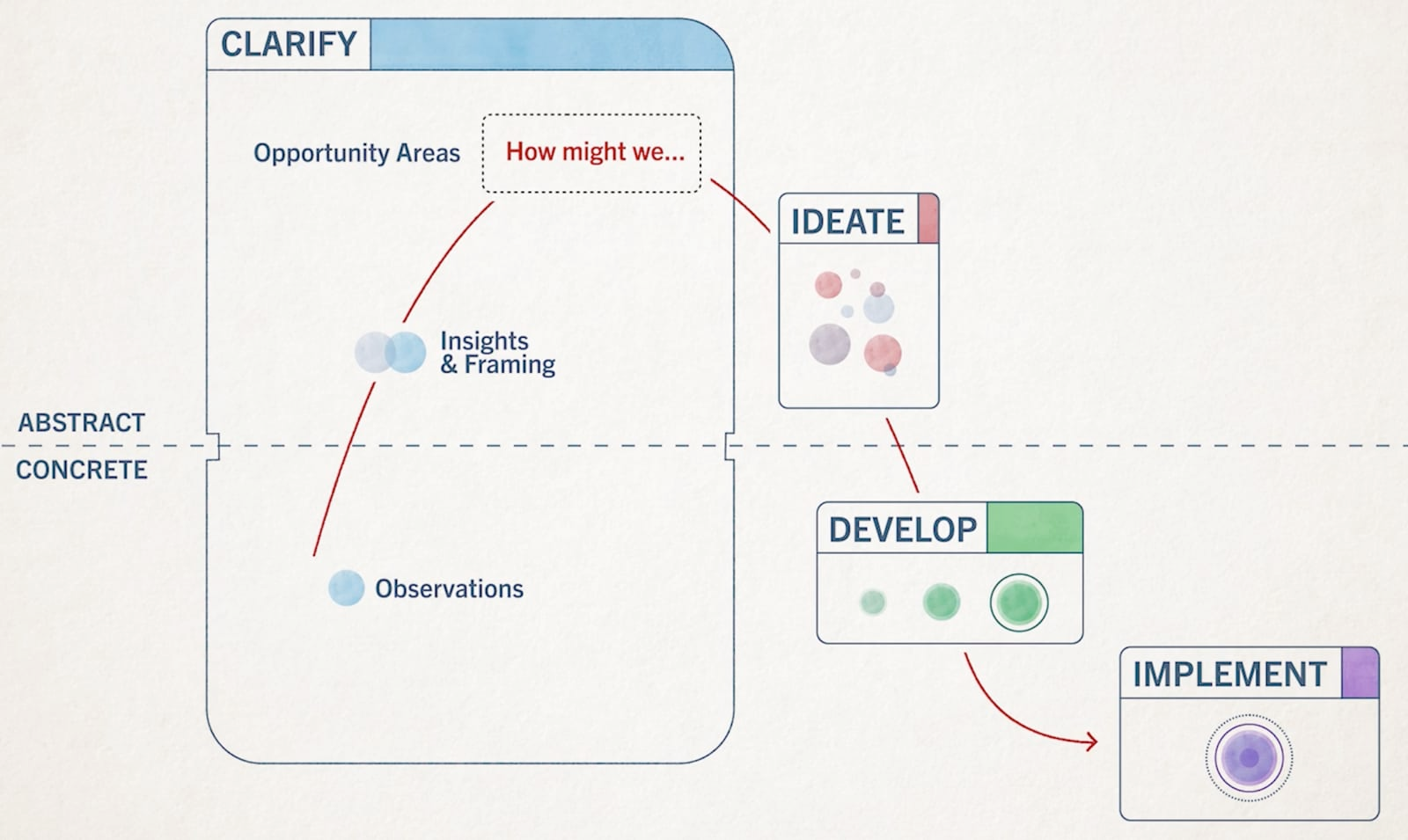

The Clarify phase in the Design Thinking process involves understanding the problem deeply and defining a clear problem statement based on user needs and insights.

We introduced Design Thinking & Innovation and let's now continue with the first phase of the design thinking process - clarify, which focuses on two things:

- Collecting data and observations about the design problem (concrete - we will focus on this part in this article)

- Reflecting on that information until you clarify what the problem really is and how you might solve it (abstract - we will tackle this part in another article)

Innovations based on user research are more effective and easier to promote than ones developed around assumptions. It requires both rigor and empathy to execute user research effectively, and it also requires a willingness to reflect on your own biases and assumptions.

Finding Pain Points

Describe a particularly annoying or frustrating experience you’ve had with a product or service. What made it so difficult, and how would you express these difficulties to the owner/creator?

Were you able to identify what made the experience in the previous activity frustrating or annoying? It can be difficult. These types of problems that interfere with the user's experience are what designers call pain points.

They represent the moments when a consumer experiences frustration, difficulty, or uncertainty when using a product, or interacting within a business or service model. One of the key things to understand regarding pain points, is that there are two types. They can be explicit, meaning users can describe what's going wrong, or latent, meaning users cannot describe how their experience might be better.

Users will be upfront about explicit pain points. But researchers will need to dig into the experience - observing, listening, and trying it for themselves to get at the latent pain points that lead to transformative innovation.

Think of it this way. If you were to call a customer service number and find yourself transferred to three different people who all asked you the same questions, that pain point would be explicit, or easy to define. Anyone would be able to point out the difficulty in that situation.

But now, let's imagine that you were interviewing users about their morning routines many years ago. A user might have described using their phone to look up the weather, so they would know what clothes to pick out for the day. In such a research situation, it's unlikely that the user would have responded with, I wish I could just ask someone to tell me the local weather every morning, instead of unlocking my phone and navigating to the app. The pain point in this situation is that people are often in a rush in the morning, and they need up-to-date information in ways that minimize demands on their focus and attention. This is a latent pain point that smart speakers, like the Amazon Echo, or Google Home address. To arrive at this pain point, researchers would have to observe the process and try it for themselves.

Latent pain points often have to do with tapping into user emotions. Recall the iPod pain points we discussed earlier. A latent pain point is that a user may regret not having a song with them when they are in a mood to listen to it. Users value the psychological comfort of knowing they can have almost their entire music library with them on their iPod.

Whether they are explicit or latent, pain points must be collected as part of the clarification process, using research involving interviews and observation. It is dangerous to brainstorm possible pain points without doing research. You may not know the product and its users enough, or you might know them too well. Either way, the results of user research will often surprise you.

Imagine that you are starting a retail website that sells clothing online. Which of the following research methods is most likely to provide quantitative feedback?

- Interviewing customers

- Watching online reviews (on YouTube, etc.)

- Ordering from similar websites

- Sending customer surveys

Option 4 is correct. Customer surveys can provide quantitative data from a large set of customers. Note that all of these methods are valuable, but each involves tradeoffs.

Interviewing customers, watching online reviews, and ordering from similar websites all provide qualitative feedback. These methods are excellent for digging into one specific aspect of an experience. However, because you are learning about the specific experiences of individuals, you may not acquire a broad perspective, and you may be receiving feedback that is subject to bias.

Questionnaires and surveys, on the other hand, are simple to create and easy to scale, and they provide broad, quantitative feedback on various issues. For example, it may be valuable to compare data like a Net Promoter Score (NPS) to measure users’ overall experience. However, quantitative data alone may not reveal important details in individual experiences and specific user journeys.

Net Promoter Score (NPS)

Net Promoter Score (NPS) is a widely used metric that measures customer loyalty and satisfaction with a company’s products or services. It gauges how likely customers are to recommend a company to others, providing a simple and effective way to assess customer experience and predict business growth.

How NPS Works

- The NPS Question: The core of NPS is a single survey question: “On a scale of 0 to 10, how likely are you to recommend our company/product/service to a friend or colleague?”

- Categorizing Respondents: Based on their responses, customers are categorized into three groups: Promoters (score 9-10): These are loyal customers who are highly likely to recommend the company to others and continue buying from the company. Passives (score 7-8): These customers are satisfied but not enthusiastic enough to actively promote the company. They are also more susceptible to competitive offerings. Detractors (score 0-6): These are dissatisfied customers who are unlikely to recommend the company and may even discourage others from doing business with it.

- Calculating the NPS: The NPS is calculated by subtracting the percentage of Detractors from the percentage of Promoters: NPS = %Promoters - %Detractors. The score ranges from -100 to +100. A positive NPS (>0) is generally considered good, an NPS of 50 or more is considered excellent, and a negative NPS indicates that a company has more detractors than promoters, which is a warning sign that the company needs to improve its customer satisfaction and loyalty.

Why NPS is Important

- Customer Loyalty and Retention: NPS is a good indicator of customer loyalty, which is crucial for business growth. High NPS suggests that customers are not only satisfied but also willing to advocate for the brand.

- Predicting Growth: Companies with high NPS typically grow faster than their competitors. Promoters are likely to make repeat purchases, buy more, and refer new customers.

- Feedback and Improvement: NPS surveys often include follow-up questions asking customers to explain their rating. This feedback is valuable for identifying areas for improvement and understanding customer needs and expectations.

- Benchmarking: NPS can be used to benchmark against competitors and industry standards, helping companies to assess their competitive position in the market.

Conclusion

Net Promoter Score is a powerful tool for understanding customer sentiment and driving customer-centric improvements. It provides a clear, actionable measure of customer loyalty and satisfaction, helping businesses to enhance their customer experience and drive growth.

Ideally, you should acquire both qualitative and quantitative feedback in your search for pain points.

The search for user pain points is the focus of many organizations with a customer-oriented strategy and a reputation for innovation. One of the most notable of these organizations is Amazon. The president and CEO of Amazon since 2021, Andy Jassy, was previously the leader of Amazon Web Services since its creation in 2003. Andy Jassy explains how Amazon keeps customer pain points at the center of management’s attention by considering the launch of a new offering as the starting line, not the finish line:

Anything you build, you don't launch it, and it's fine, and you don't have to worry about it. The truth is that launch is really the starting line, not the finish line. So anything that you're working on, you have to have good feedback loops to know what customers think. One is you get a lot of email from your customers telling you what they think. Another really good source is if you have good hashtags that give you definition on Twitter about what customers think of your different offerings. Customers aren't shy, and they're particularly not shy on Twitter. Another really good one is if you could build mechanisms in all of your product offerings that allow customers to leave feedback in line as they're experiencing the product. And so we have a mechanism we use here at Amazon a lot that we call "How's My Driving?" which is, on many of the pages and services we offer, we let people tell us either while they're going through it, or we ask them afterward, how did we do? What did we get right? Was it easy enough for you? Would you recommend it to friends? And those are all examples of feedback loops and mechanisms that allow you to constantly see where you are regarding what customers think of your product. The job is never done. And I think if we all understand it and understand you have to be working on it constantly, moving forward, it's easier to get it right.

To find the pain points and latent needs that spark innovation, observe people as they use products and services, and listen to their experiences. This applies to strategies, business models, and management practices, as well as new products or services.

Imagine that you were hired by a major consumer-goods corporation to help develop a stronger liquid cleaner. After previous products failed, the corporation asked you to observe users to learn more about the type of cleaning product they need. Over time, you notice people at home repeatedly going through a mopping process.

The explicit pain points for mop users are the following:

- The mop gets dirty quickly.

- Mopping uses a large amount of water (so it's wasteful).

- It’s heavy work.

- It’s very messy.

- It’s difficult for many elderly and physically disabled people.

The following are some latent needs for mop users:

- Users dread the task. They put it off because they dislike it.

- Users want to take pride in keeping their home clean. They are ashamed when others see it dirty.

- Worrying about injury is a psychological burden for older users and their families.

- Users daydream about an easier way to clean - a process that is over as soon as possible and with minimal effort.

The biggest insight from this research process was the final latent need. People didn’t need a higher-strength cleaner for their floors: they needed an easier way to clean.

Even when you are tasked with solving a specific problem - like developing a stronger liquid cleaner - it is crucial to remain open to different problems with a strong consumer need.

If you're doing your user research, when does it not surprise you? You should always be surprised, and if you're not surprised, you're either not probing deep enough, or you're not letting yourself go off script enough to allow yourself to be surprised. Doing good user research, is having an open, curious mind, the mind of a child. Even if you've seen something 20 times, feel like and behave like you've never seen it before; allow yourself to be surprised. It sounds much easier to do than it actually is because for many of us we've been rewarded by knowing the answers, and so it's hard for us not to want to finish the sentence of the person that we're interviewing or listen with an open mind or ask naive questions because we're trained to be the expert. When you're the interviewer, you're not the expert. You're the curious, interested party that is getting this gift of being brought into someone's life, and I think if you approach it that way, you will always find something that's surprising.

Using the AEIOU Framework to Guide Your Research

In 2010, US public schools were serving lunch to 31 million students, and 17 million of them lived in food-insecure households. This meant that students relied on school lunch for many of their daily calories. In addition, one-third of US children at the time were considered overweight.

Federal policymakers decided to fight childhood obesity and hunger at the same time. The result was the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act, which introduced the following nutritional guidelines in schools across the United States:

- Calorie restrictions for each meal

- Fat and sodium restrictions

- Larger servings of fruits and vegetables

- Restrictions on serving sizes of protein and carbohydrates

- Requirements that grain servings be at least 50% whole grain

Schools that followed these guidelines would qualify for additional government funding through the National School Lunch Program. Numerous people were affected by the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act, including students, parents, cafeteria workers, administrators, and school boards.

The 2010 Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act was clearly a very worthwhile and well-intentioned law, but the initial reaction to the law was mixed. This was likely because it simply did not reflect a comprehensive understanding of user needs and behaviors.

Legislators developing the act focused primarily on the school lunch problem from the view of what could be done with guidelines and what professionals felt would be best for kids. What legislators didn't take the time to understand completely was the emotional, psychological, and other needs of the children themselves, nor did they fully investigate the view of the administrators who would be implementing the program.

So what did some kids do with the new healthy meals that appeared in their cafeterias in 2011? Many of them threw food away. Smaller serving sizes at higher prices, limited meat and grain portions, no French fries, nachos, and chocolate milk? Many users of the school lunch programs were unhappy. The media gave attention to lunch boycotts, and participation in lunch programs fell significantly.

In fact, overall participation in school lunch programs declined by 1.2 million students in the first year of the program. This was bad news for budgets that were already a struggle. There were additional budget concerns due to increased food costs, as well as issues with government reimbursements and oversight, and compliance disputes between states and schools. What could have been done to prevent this?

The following are some questions that you might have considered before implementing the new law:

- Which foods are most popular and most unpopular among students, and what opportunities does each category provide?

- What is the school atmosphere like? Are there differences in nutritional needs or eating habits among students? Is there a social hierarchy among students that might affect implementation?

- How will the policy be implemented by the administration? Will it be narrow or broad in scope? Will teachers be engaged and supportive?

- How will the changes be administered, and how will they affect student participation in lunch programs?

- Do different schools have different budgets and staff situations? Are all schools equally equipped?

- Will there be parental outreach, and collaboration between schools and families?

- What is nutritional education like in schools? Are there set or habitual behaviors that should be considered?

Importantly, budgets are tight in many school districts in the United States. Some school kitchens are old and haven’t received funding for equipment since the 1980s. Decreases in student participation can have an impact on a food-service director’s ability to keep staff.

However, it would be worth overcoming resistance and challenges to make a positive impact and create a culture of healthier eating among all children, especially those at risk of going hungry.

The people trying to make school lunches healthier for children were in a difficult situation. They had to implement guidelines that would affect a staggering number of schools. These schools had children from various cultural and economic backgrounds, and they had different nutritional needs.

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act had a rough start because it was results focused rather than user focused. So what happened to the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act? Through the use of follow-up programs like student education and participant training, attitudes about the new school food policy changed over time, and the program eventually gained traction.

One study noted a 47% reduction in obesity among children in poverty. Could these numbers be higher? Can we measure success in statistics alone? For now, we can celebrate progress, while noting that, from a design perspective, it is essential to do your homework.

In contexts like the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act, where many groups are involved, we can make implementation smoother by taking a more systematic approach to collecting observations. Identifying the latent needs of all stakeholders (including students in this example) can result in a more user-focused solution.

However, in addition to users, there are many other characteristics of the design context you can observe. Which parts of a school cafeteria, apart from users, would you want to observe if you were researching this problem?

To start organizing observations in a deeper and more thoughtful way, consider the AEIOU research framework. Created by Rick Robinson, Julie Bellanca, and other members of the Doblin Group in 1991, the AEIOU framework presents several ways of coding the observations collected during user research: activities, environments, interactions, objects, and users.

Let’s learn more about these perspectives by examining how customers flow through a coffee shop.

- Activities: What happens? What are the primary, secondary, and peripheral activities related to the design context?

- Ordering and paying for your drink would both be primary activities - the main actions needed to complete the task.

- Secondary activities might include standing in line, waiting around for your drink, or navigating the options for milk and sweeteners. These are optional (e.g., if you ordered online, you might go directly to the pickup area) but closely related to the main task.

- You may even want to consider activities that are not directly related to the coffee shop itself, but are nevertheless related to the design problem. For instance, driving to work might be a related activity, if some customers pick up coffee on the way to work and consume it in the car.

- The scope of your observations will depend in part on time constraints and on the resources available to you, as well as on your goals in undertaking the design project.

- Environments: Where do things happen? Are there multiple environments within one place? What are the characteristics of each one?

- The coffee shop itself is an environment, but it contains many smaller environments, such as the ordering line, the seating area, the register, the waiting area, and so on.

- Each environment might have its own characteristics, such as narrow, bright, cramped, or open.

- Other indirectly related environments might include customers’ homes and workplaces. Customers might place their orders from those locations and/or eat and drink outside the shop itself.

- Interactions: When and how do people interact with other people, things, or the environments? Are these interactions planned or spontaneous?

- In a coffee shop, there are many interactions beyond the customer paying for their order. People interact with each other in line, with the food options as they wait, and even with the door on their way out.

- Importantly, we might observe unplanned interactions, like people blocking each other’s view in the waiting area or lining up in a way that bothers seated guests.

- Interactions outside the shop might include a customer giving a family member a gift card, or employees reviewing their benefit options.

- Objects: What objects are present in the activities and interactions? Which seem most and least important? Are any of them puzzling?

- Are the lids for the disposable cups easy to fit? Are some types of lid being used more often than others?

- Do specific payment methods or promotional stands slow down the line significantly?

- Objects related to the broader design context might include a customer’s keys (can they handle the keys while also holding a cup of coffee and a bag of food?) or the cupholder in their car.

- Users: Who are the people in each activity, environment, and interaction? Are there different groups of people? What are their characteristics?

- Do different types of customers enter at different times of day, and do they order different drinks?

- Do certain groups sit in different areas?

- Are employees happy with their jobs?

- Are locals happy with the location of the shop?

- More broadly, users might even be expanded to include friends and family of customers or employees, who are affected by their purchases or by the way they are treated at work.

In the AEIOU framework, the term user is broad!

Note how grouping similar observations together can lead to ideas. Collaboration makes it less likely that important observations and ideas will be overlooked.

This coding provides you with a comprehensive overview of the context of the problem.

Structuring Observations Using Journey Maps

Let's see how to:

- Define journey maps and create maps that organize events into meaningful phases

- Analyze journey maps for pain points, opportunities, and challenges

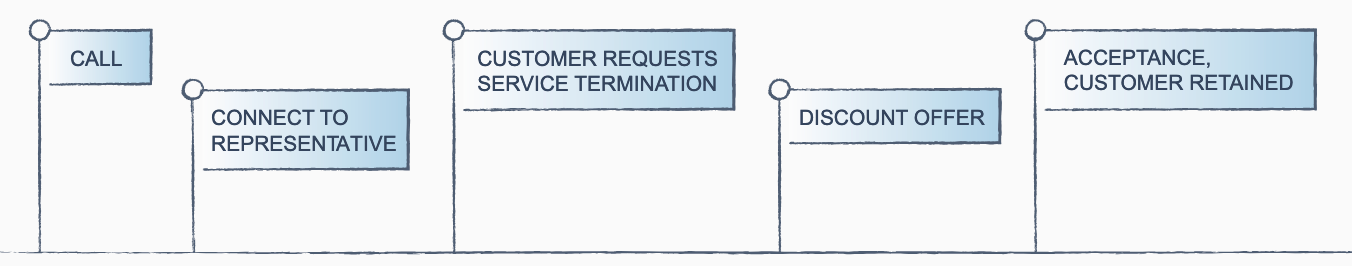

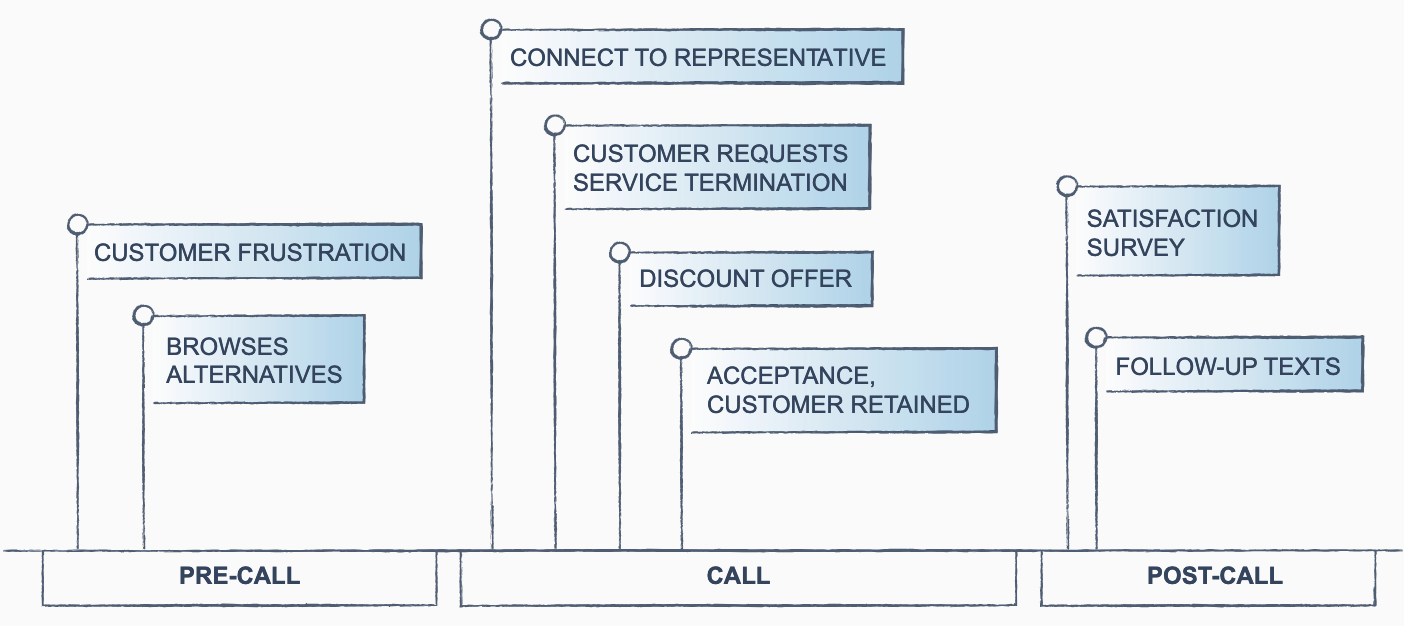

Researching the customer journey caused T-Mobile to rethink the approach to customer service, leading to an innovation called the Team of Experts.

The explicit pain points in this situation were receiving an impersonal greeting from a robot, and then being transferred to different operators each time. This can be frustrating for anyone, but importantly in this case, it connected to the latent need behind contracts and roaming fees as well: customers wanted to feel trusted and supported. When customers didn’t recognize the person on the phone, they couldn’t build a personal connection.

T-Mobile’s innovation - the Team of Experts - was to pair customers with specific groups of representatives. This innovation addressed the latent need and led the company to introduce more strategically useful performance measures for representatives and for customer service as a whole.

An important tool for structuring observations about users is the journey map, which creates a timeline for chronologically organizing what you know about the context of the design problem. A journey map also challenges your assumptions about when the journey truly begins and ends, thus identifying as many opportunities for innovation as possible.

Before you begin creating a journey map, start with these key questions:

- Where does the user or customer journey begin and end? Like an AEIOU table, it should always start with observations whenever possible. While you can create journey maps based on what you believe the user experience is, maps based on research are more fruitful. Even after you have created a first draft, you can challenge yourself to push further.

- Are there steps even earlier or later in the journey where value could be created?

- Can you organize the main events of the journey into meaningful stages?

- In each stage, what does the user experience look like?

- What decisions need to be made, and who makes them?

When you have answered these questions, you can visualize them as simply or elaborately as you wish.

And the following image demonstrates how the map changes when we push it out further, creating steps before and after the initial draft, and organizing these events into meaningful stages.

These are some rough generalizations of what might occur - but they demonstrate how expanding a journey to incorporate events before and after the main interaction can create opportunities.

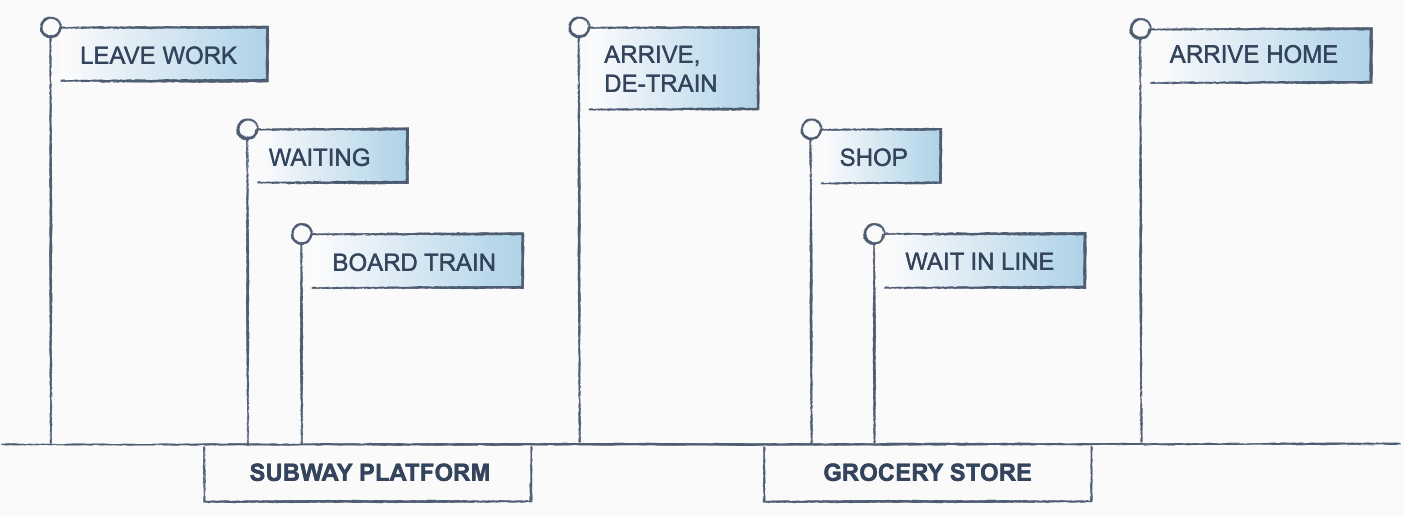

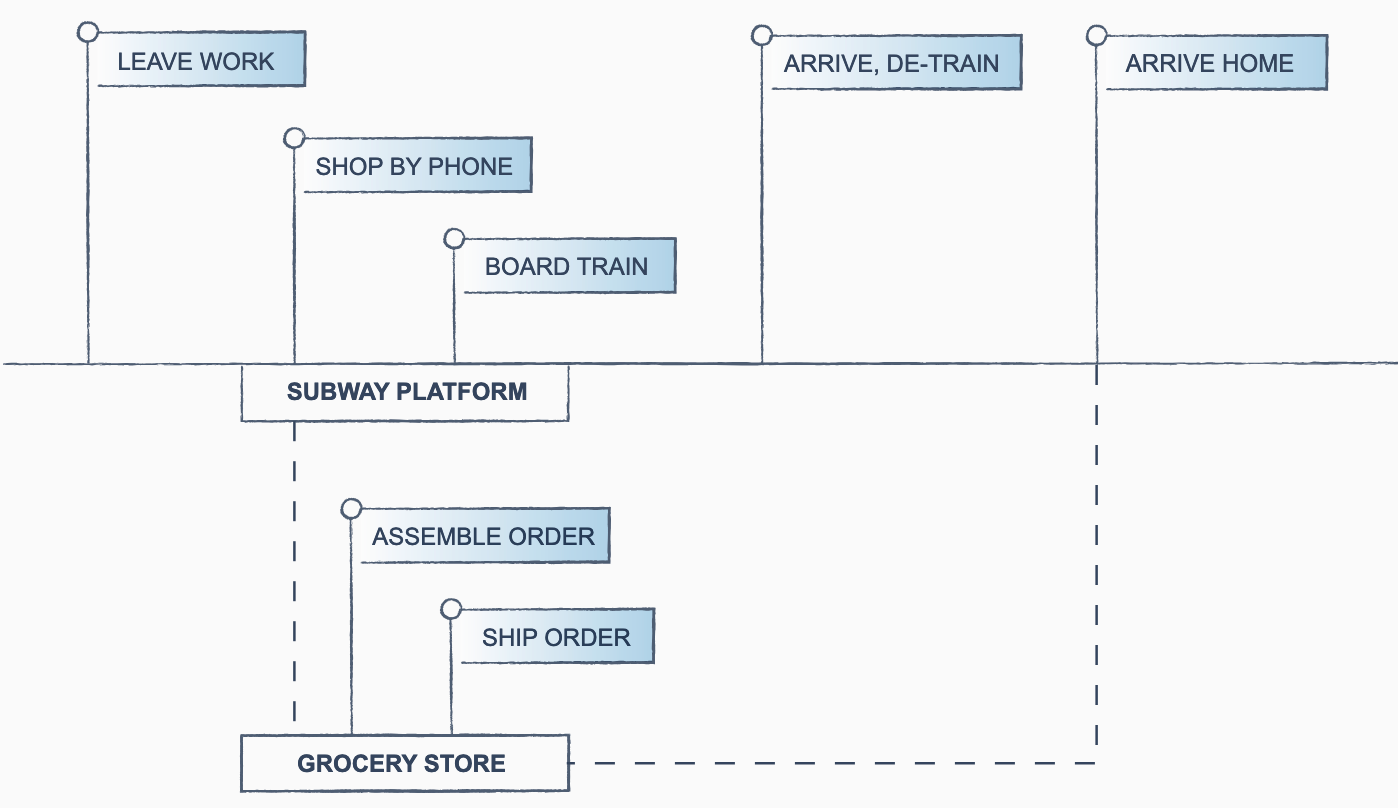

The following customer journey was created by following several people as they made the trip from work to the grocery store and then home. There are two key phases: waiting on the subway platform, and shopping at the store.

The design team decided to focus on one explicit pain point: “I need to shop when everyone else does because we’re all on the same 9 to 5 schedule.”

In this case, creating the journey map led to key realizations: customers aren’t spending most of their time in the store, and almost all the time is spent waiting.

- Customers spend 20 minutes walking to the station and waiting for the train.

- They wait in line at the store for 5 to 10 minutes.

- They spend another 30 minutes getting home.

Even if improved customer flow in the store results in five minutes less in line, this will not dramatically reduce the time spent waiting, or address any of the latent needs.

So, how can the store give customers their time back? Can the customers somehow use their phones for shopping? That would transform the waiting time in the first subway-platform stage into shopping time as well. This might eliminate the second stage altogether.

At this stage, there are a number of unresolved questions. What issues related to desirability, feasibility, and viability might arise from this phone-based shopping idea?

The following are examples of unresolved questions:

- Do customers want to shop by phone?

- Could this activity easily happen in the time spent on the platform and on the train?

- Could the store install a kiosk in the subway station where people could make quick online orders with their phones?

Your initial reaction may be that these are strange or unworkable ideas - but this is actually a good sign.

When you first note observations in the AEIOU framework or a journey map, you may find yourself thinking of solutions already. You may even be inclined to think about these ideas in terms of marketability and feasibility and assume they are impossible. But this would be a mistake.

The early phases of design thinking are a time for divergent thinking, generating as many ideas as possible without judgment. There will be a time for evaluating ideas later, when you have a clearer idea of what a comprehensive, user-centered solution should look like. It is natural to worry about feasibility and viability. But keep in mind that changing social and contextual factors change how we interpret ideas through these lenses.

The most recent example is the COVID-19 pandemic, which has made an enormous impact on the perceptions of feasibility and viability of existing models.

In the first stage of the design thinking process, teams should prioritize identifying as many opportunities as possible without ruling anything out.

Adjusting the Scope of Your Journey Map

Let's see how to:

- Apply understanding of the AEIOU framework to create journey maps based on observations

- Expand a customer journey map to create new opportunities

To practice more with journey maps, let’s consider another example. In your opinion, what is the most difficult part of moving from one home to another?

- Coordinating a moving truck

- Packing

- Logistics (transferring addresses, signing up for utilities)

- Cleaning

- Unpacking

- Other

Even if you have never coordinated a move, you may have noticed, by reviewing all these options, that the customer journey is broad. It can extend into the weeks before and after the actual moving day.

Let’s explore the case of Gentle Giant Moving Company, a Boston-area business that centers its services on the pain points and latent needs of both moving employees and customers.

I'd now like you to imagine that you're an upper-level manager at Gentle Giant, a moving company based in Somerville, Massachusetts. You want your company to become known for providing the best customer experience in the region. And you're ready to make the changes needed to move in that direction. How? By using research to improve the user experience. So let's get started.

What would you do to begin your research? Assuming that you're taking a structured design thinking approach, how would you begin your search for explicit or latent pain points related to your service?

Imagine that you are planning to make AEIOU observations for a move from one house to another. Which phase of the process has the most interactions between customers and the moving company?

- Estimate and assessment

- Packing

- Moving day

- Post-move

You probably selected ‘moving day’ as the phase of most interaction. There are numerous possible interactions between customers and employees on the day of the move, typically more than in other phases. For example, there is the arrival, a survey and checklist, questions about individual items to move, food and drink arrangements, breaks, scheduling, payment - the list goes on.

As a result, you may be tempted to focus on this day for user research, but it is equally important to make observations at other times, as you may find opportunities for new interactions that can cultivate the customer relationship and solve pain points.

The following table contains broad AEIOU observations of the moving process. Using this overview, you could begin constructing a journey map and making more specific AEIOU observations of specific activities or environments. In this way, the two tools complement each other.

Many people know the difficulty of packing, but other sources of anxiety, such as parking and payment, would be equally valuable to research.

To solve these customer pain points, Gentle Giant Moving Company adopted an innovative approach: developing its workforce and focusing on their needs as well. Experienced team leaders could provide superior service and ease anxieties along the customer journey.

Let's see what they actually did to improve their user experience and expand their market share. The company was founded in Massachusetts in 1980, and has since racked up a number of awards for being the best movers in the Boston area. How did they do it?

One of the main reasons for the company's success and continued expansion has been its management strategy of putting employees first. The rationale for this strategy was the owner's belief that fostering a satisfied, independent workforce would encourage employees to empathize with customers and resolve every scenario with a customer focus.

A key phrase in their recruiting efforts is still "We develop leaders, not laborers." To support this initiative, Gentle Giant provides its movers and other customer-service employees with special benefits and creative training, including the following: guided role-play with improvised actors, special training on packaging and handling items that are fragile or precious, an on-site gym that is free for movers so they can keep themselves in peak condition for their physically demanding job.

In addition, when creating employee guidelines for their movers, Gentle Giant designed each customer interaction with intention, noting things like how customers might observe movers placing objects, taking breaks, and so on.

In the end, Gentle Giant's human-centered approach to the moving process resulted in a creative approach to employee development and extremely high customer ratings and satisfaction rates. Over time, this has translated into consistent success and a reputation for providing excellent service.

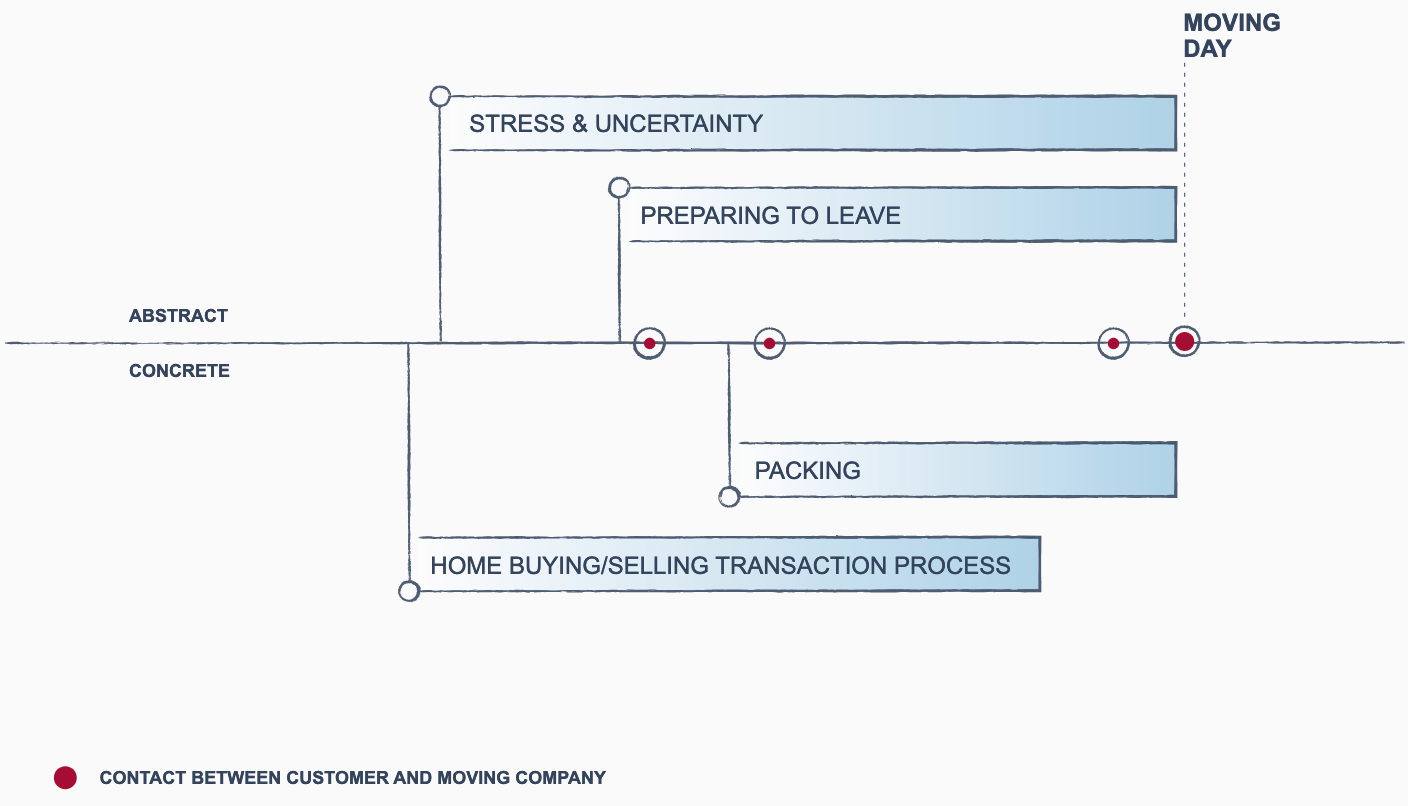

The following sample journey map identifies two events that customers experience before moving day: the transaction process of buying and selling a house, and packing for the move. It also highlights where the customer would interact with Gentle Giant.

The top of the journey map notes the stress and uncertainty that customers might feel during the other events, and the mental preparations they must make. Overlapping abstract feelings are a sign that customers may have too much to think about.

This is how journey maps can prepare organizations to thoughtfully design user interactions. When you examine the map, you can understand not only when customers might feel stressed but also why.

The example journey map is a good start, but does it truly represent the entire customer journey? Perhaps yours extended further. By expanding the journey map to include more segments, we can better analyze the user experience.

Your ideas for the journey map may vary, but some examples are settling in or unpacking. Those are clear, concrete stages. How would people feel during this time?

And most importantly for Gentle Giant, could they interact with clients to resolve any latent concerns or pain points? For example, could they follow up to ask if anything was damaged in the move or ask for feedback about the movers?

In addition to a satisfaction survey immediately following the move, Gentle Giant actually conducts an additional annual survey of all its customers from the previous year. This gives customers who are busy building their new life in a new home additional time to process the experience and think of feedback.

Gentle Giant's focus on the customer journey resulted in improvements elsewhere too. For example, the email receipt for the customer's moving deposit also contains links to Gentle Giant video tutorials on how to best prepare for moving day. This addresses the latent pain point of being overwhelmed and not knowing where or when to start.

In summary, muscles may be very important for getting at explicit pain points and avoiding problems on moving day, but to get at the latent pain points, the ones that clients can't really define, Gentle Giant realized they needed to connect with people's emotional needs as well.

In this case, and in many other cases, having the right tools to really clarify what needs to change can make a difference. The AEIOU framework can help you better understand exactly what you are looking for. Journey maps provide structure for thinking through a situation and making sure you haven't missed anything, and then taking time to review and adjust the scope of your journey map can allow you to expand upon and organize your data. This can help you better identify and further refine the explicit and latent pain points that are relevant to your research.

It is so helpful to use journey maps as tools to imagine where journeys might go wrong, as it can lead to surprises in your observations.

So far, we have explored tools that catalog what - AEIOU, and the structure - journey maps, of design problems. Next, we will explore a systematic way to approach the how.

Further Observations: Look, Ask, Try

Let's now:

- Explain the Look, Ask, Try framework and how it relates to the tools covered earlier (AEIOU and Journey Maps)

- Apply What, Structure, How observations to a business problem

An effective way to begin research is by participating in the context of the problem to learn how users interact with the people, objects, and location in question.

To structure this approach, the design firm IDEO uses a simple framework called Learn, Look, Ask, Try, created by Bill Moggridge and Maura Shea. We have shortened it to Look, Ask, Try:

- Look: Observe carefully and deeply, and check your assumptions.

- Ask: Engage with stakeholders and develop rapport to explore and uncover new ideas and perspectives.

- Try: Go into the field to learn by doing. If this is impossible, try using props or other physical approximations.

Why is it important to observe the user context in person?

As you learned earlier, users usually cannot articulate the latent needs that lead to innovative solutions. Moreover, there may be a significant gap between what they claim to do, and what they really do.

Interviews require time, patience, and soft skills like projecting a positive attitude. As the researcher, you want to ask curious questions, and you want to avoid directing the users towards specific answers. This is a difficult skill developed through practice.

Christi Zuber describes an example of this kind of research from her experience as the director of innovation at the healthcare organization Kaiser Permanente:

One of the efforts we were working on was looking at people in the hospital setting getting ready to go home. The hospitals were saying, we really need to make sure that we get this discharge process right. So the term 'discharge' in a hospital setting means all the final things that are happening when someone's in the hospital that need to take place for them to safely go home. That might be getting their medications and having final discussions with their physician, getting their IV taken out, getting materials that they need, whatever it might be. So the focus when we started this was really the discharge process. What is happening in the discharge process? Who's involved in it? How long is it taking? When we started doing our user research, I mentioned how much I really love looking through the lens of the journey of the people you're trying to design for, so we started looking through the lens of the people that were in the hospital from the time they got into the hospital through the discharge process and actually to the time that they got home. We even went so far as we hung out with them in the hospital. When it was time to go home, we'd say, hey, can we head out with you? And by this point you really often really bonded with these people. So we'd ride home in the car with them and watch them get set up. How did they get there and so forth. I remember a phrase that one woman said is - later on, when we were actually home with her, she said - "I don't know why they told me all this." Because we were asking, tell us about those last few days that you were in the hospital, those last few hours in particular. And she said, "I have no idea what they said," and she was actually a nurse by background. She was a retired nurse, but she said, "I had one foot out the door. I didn't hear anything that they said." Looking at it through the lens of the people that you're designing for will yield these insights that sometimes when you hear them you go, oh, of course. Of course that's right. But in that particular moment, that's not the lens that you're looking at, so that's why it's really important to talk to people and observe them and be curious and open.

In her example, Christi Zuber’s team began with the patient journey through the discharge process but discovered that there were even bigger challenges. It's a powerful example of what you can learn by going into the field and actively looking, asking, and trying.

The tools we have explored so far are designed to help you uncover pain points and latent needs. Together, they provide a framework for organizing your observations into a more complete picture of the design context.

If you are designing a new product, service, business model, strategy, or management practice, you may ask yourself the following questions:

- What is happening? What is the overall context of the experience? (answer the AEIOU questions)

- What is the structure of the experience? Where are the opportunities for innovation? (construct a journey map)

- How can you understand the user experience? (observe deeply using Look, Ask, Try)

Using this framework to identify latent needs is especially valuable because innovations that tap into how people feel about and connect with a product or service are very impactful.

Consider the following observations, representing the full What, Structure, How of the innovation context for T-Mobile:

- What: Business travelers are on the move. They are on planes and in taxis, and then arriving at a hotel. They conduct business and entertain business partners, while also keeping in touch with family back home using cell phones, office phones and hotel phones.

- Structure: The user plans travel, leaves home, arrives in another area, conducts business and day-to-day activities via cell phone, returns home, then receives a surprise bill from their mobile carrier with high roaming fees for calls outside the country.

- How: A customer describes receiving a phone bill with enormous roaming charges when her partner called about their child being sick.

You have decided to eliminate roaming charges. Where on this customer journey (described in the Structure bullet point) do you see an opportunity to surprise and delight users by keeping them informed about this change, thus reinforcing its value?

When you travel, there's going to be an extra charge, and it's called roaming. You need to be careful. And customers didn't really have the imagination to say, you should eliminate that. What they did have is passionate anger when there was a surprise bill that just seemed unfair and when there wasn't warning and there wasn't a sense of control on their part, and that's what really makes people upset, is when they feel like they've lost control.

T-Mobile knew there was an insight here they could act on. A big piece of what they did, and still do, is act on these insights, but then rapidly measure what happens.

What happened here was the amount of customer love and sentiment and word of mouth that went around, particularly among a new segment for T-Mobile - prime credit suburban consumers, professional workers, enterprise employees, people that travel a lot - suddenly this segment where T-Mobile were underrepresented was talking about T-Mobile and telling their friends about T-Mobile, something concretely different that T-Mobile was questioning.

When you get off that plane in Europe or drive across the bridge into Canada, it should just work, and by the way, there's nothing to sign up for up front. So there's this surprise and delight moment, not only the removal of something that makes people passionately angry, but a surprise and delight moment. When you get to the other side of that bridge, you just get a text from T-Mobile that says, don't worry, this is included in your plan. It's totally free.

Think about an innovation problem at your organization, or one outside your organization, that you find interesting. What tools and frameworks (AEIOU, journey maps, or Look, Ask, Try) do you think would be most useful in expanding your understanding of the problem? What experiences would you be excited to expand your understanding of?