Concept Posters

Develop: An Experimentation Mindset - Idea Selection and Evaluation

Let's continue from the previous article, now we will see how to:

- Use the concept-poster template to create concepts for prototyping

- Define critical questions and explain their relevance to the develop stage of design thinking

Now that we have explored the pay-phone concept using a variety of tools, let’s reflect on basic assumptions about the innovation.

Which of the following questions around desirability, feasibility, and viability would most concern you if you were developing a new device for the sidewalks of New York City?

- Will pedestrians notice the device?

- Will pedestrians know what it can do, and how to interact with it?

- Will it stand out from other distractions on the street?

- Will it survive weather in different seasons outside?

- Will it be able to stay online and powered?

You may notice that we use the phrases “critical questions” and “assumptions” somewhat interchangeably. This is because critical questions are the questions you ask to uncover the assumptions underlying your concept.

For example, asking, “Will pedestrians notice the device?” highlights an assumption one might make that people on the street will be able to notice the new pay phone device at all. In fact, this is not a given. If the device is too small, or not in the right location, passersby might miss it entirely. Critical questions can help draw attention to design aspects you may have taken for granted, or otherwise overlooked.

Expressing these assumptions in question form allows you to create a testable hypothesis for an experiment. For instance, once you are aware of the question, “Will pedestrians notice the device?” you can build prototypes of different sizes to help you answer it, and redesign as necessary.

Thus, these critical questions and assumptions are the foundation for the next step in moving your innovation from the abstract to the concrete: prototyping.

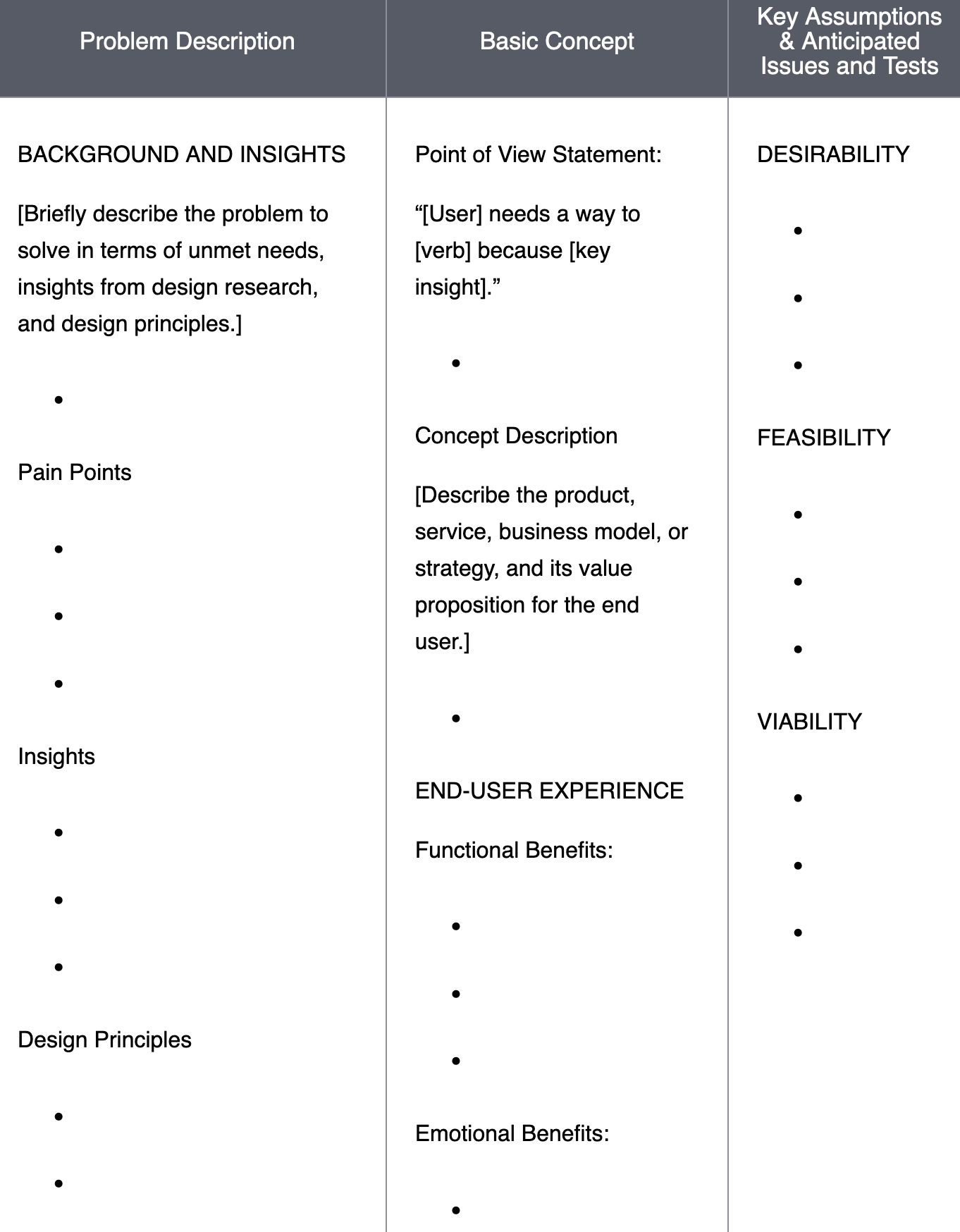

A useful tool for identifying these critical questions and reviewing your knowledge of the concept is the concept poster.

The concept poster collects the most important information related to the concept and presents it clearly in one place. In addition to a brief elevator-pitch description of the innovation, the concept poster includes the following information:

- The design principles that guided ideation.

- The key stakeholders who would use and implement it.

- The functional and emotional benefits to the user.

Note that both kinds of benefits transfer easily from the attribute-value mapping. The functional benefits come from the attributes, and the emotional benefits come from the values.

Finally, you must write the key assumptions behind the concept and any anticipated issues related to its desirability, feasibility, and viability. For example:

- In the desirability section, have you made any assumptions about how users will interact with your service innovation? How might you test these assumptions?

- For feasibility, what assumptions have you made about the materials for your product innovation or the skilled labor required to produce it? How might you test these assumptions?

These questions will be essential to the prototyping process. Identifying these assumptions and issues now, before you proceed to testing, will provide structure and focus to your prototypes. Ultimately, this approach will save time, money, and energy later in the development process.

The concept poster collects the most important information related to the concept and presents it clearly in one place. It is essentially a first draft of your concept, and a simple way to collect positive and constructively critical feedback. Note that the bullet points in the following table are blank as an example of where you would fill in text.

The preceding template demonstrates that you already have most of the information needed to complete a concept poster.

You should use all of it to develop the third column’s critical questions: the assumptions around desirability, feasibility, and viability that you will need to test before you begin building and implementing an innovation concept.

The following is a partially complete concept poster for frog design’s Beacon concept (you can format a concept poster however you like).

- Pain Points to Address

- Less useful than smartphones to most residents

- No widespread public internet or Wi-Fi access

- Outdated method of operation (coins)

- Limited functions in emergencies

- Design Principles

- Modern and approachable

- Equal and free access to information

- Better community safety and personalization

- Point of View Statements

- Young tourist needs a way to connect with local offerings because a trip that feels personal will be the best experience.

- City government needs a way to communicate with the public because timely messages can greatly improve public safety when power is disrupted.

- Cellular operators need a way to bridge interruptions in service because bandwidth needs will only increase in the future.

- Description of Concept

- A digital connection to the city and local neighborhoods, the Beacon will help locals communicate and visitors find rewarding experiences.

- End-User Experience

- Functional Benefits

- Internet connectivity, charging ports

- Quick connection to the fire department, police, or cab service

- Maps, weather, and other local information

- Emotional Benefits

- I feel comfortable navigating the city

- I’m excited to discover new activities in the neighborhood

- I feel engaged by the device, even though I lack technical skills

- Functional Benefits

The following are just a few examples of critical questions. Note that they expand the context to additional stakeholders, like utility services and advertisers.

- Desirability: Will users look up information on the Beacon instead of their phones? Will they be enticed by the interface?

- Feasibility: Can the Beacon deliver a reliably fast Wi-Fi connection? How will it integrate with existing utility services?

- Viability: What advertising opportunities can the Beacon offer? Will advertising revenue be enough to support the device?

Think back to the example of the PlayPump we covered in one of the previous articles. There were several key assumptions around desirability, feasibility, and viability that prevented it from fulfilling its potential. Innovation is inherently risky, but prototyping reduces that risk and makes issues easier to address later.

Had frog design not identified and tested many of the assumptions you explored above, it may not have gotten far. The Beacon’s visibility on the street, its ability to withstand different temperatures, and the desirability of its interface were all assumptions Frog Design identified and tested thoroughly. Most importantly, they did this in stages.

The earliest critical questions focused on the innovation’s construction and how it would survive in different urban environments. Later, the critical questions shifted to finer details of design and interaction. Businesses often jump to constructing a complete pilot prototype, but this approach can be counterproductive. Rushing the development of an innovation makes it harder to identify assumptions or even to collaborate effectively.

For example, engineers and interaction designers could work together to innovate on existing IBM mainframes, but with an entirely new innovation like pay phones, these teams might naturally clash on direction. The concept poster provides an opportunity to step back and identify which critical questions are most essential to the innovation’s success and must be tested first.

Your work in the clarify and ideate phases of design thinking builds toward the creation of this concept poster. However, as you test and iterate on your innovation, you may need to return to user research or ideation. If you do, be sure to update the concept poster and revisit your assumptions. As the attributes and values of a concept change, so will the critical questions.

Think of critical questions in the develop phase as serving a role similar to design principles in the ideate phase. Critical questions provide structure and a way to evaluate your work to ensure it remains user-focused.

A similar approach to the concept poster is Amazon’s set of “working-backwards” documents. These include a press release and a frequently asked questions document detailing the new product and why customers will care about it.

As Amazon CEO Andy Jassy explains this approach in the following video transcript, consider the assumptions about your own innovation, and how you would communicate them in an environment like Amazon’s.

We have a set of leadership principles that are very important to our culture, but it starts with customer obsession. We talk about it all the time, focus on it in all of our reviews, and build our regular rhythms and mechanisms in the company around it.

For example, when we do new product development, we won’t write a line of code until we work through what we call our “working backwards” set of documents: a press release and a frequently asked questions (FAQ) document.

The press release forces us to flesh out the benefits of what we’re offering and decide whether, if we built it, it would really matter to customers. This avoids the common scenario where, after spending significant resources to build a product, the team asks, “Why did we think customers would care about this?” The goal is to ensure that if we go through the effort to build something, we believe it will truly move the needle for customers and, ultimately, for the business.

The FAQ document details how the product will work. It covers key elements such as:

- Who the customer is.

- Why the customer will care.

- The key features and how they differ from similar offerings.

- How it will be built.

- Pricing dimensions.

- The user interface design.

These documents force us upfront to determine what we’re building, how we’ll build it, and whether it’s viable. While it requires extra effort early on, it streamlines the development process. Teams can proceed with clarity, without constant audits, knowing everyone is aligned on the vision and execution.

This approach ensures that every time we build something, we start by asking: Is this what customers care about? Is it right for customers? Many of the questions in the FAQ document focus on customer needs, including:

- What do customers want?

- What do your best customers think?

- What new customers could benefit from this offering?

Having mechanisms like these drives customer focus at every stage of the process.

Optionally, you can meet with a partner or your team—or simply think on your own—to consider how you might convert your innovation concept’s key assumptions around desirability, feasibility, and viability into an FAQ document. Consider the following questions:

- Who is the customer, and why will they care?

- What are the key features?

- How do these features differ from those of similar options?

- How are you going to build it?

- How will you determine pricing?

- What does the user interface look like, if there is one?