Defining Behavior Prompts and Creating a Cycle

Ideate - User Values and Behaviors - Designing for Behavior Change

Learning Objectives:

- Define the different types of prompts and how they support behavior change

- Analyze a loop of behavior-change prompts

We will continue building on Improving Motivation and Ability: The Fogg Behavior Model.

As we discuss broad trends in motivation and ability, especially in the context of composite personas, keep in mind that each individual has a variety of factors that will influence how they behave. Some of these factors are personal, while others are influenced by societal constructs, as Christi Zuber explains in the following video transcript.

I think we often really underestimate the societal construct and its around us. So it is really important when you’re trying to create a behavior change. And this, I think, is also very intertwined with what we’re talking about—people’s context.

People’s context is really important. People are not an island. People are influenced by what’s around them, what’s accessible, what other people are doing, what’s easy at hand, and what’s now difficult or more expensive because they’re being disincentivized to do something. All of those things make a really big impact.

So I think when you’re talking about behavior changes in society, you have to understand the construct that people are in. And I think motivation is wonderful for creating those repeat, what we would call habits, that hard-wiring that you want to do it again and again and again because it feels really good.

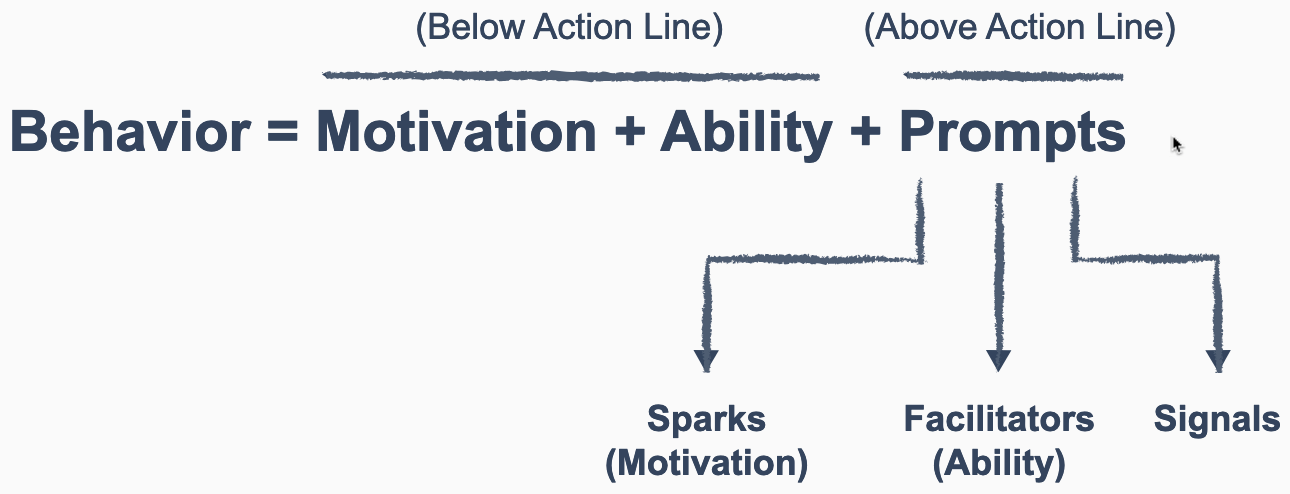

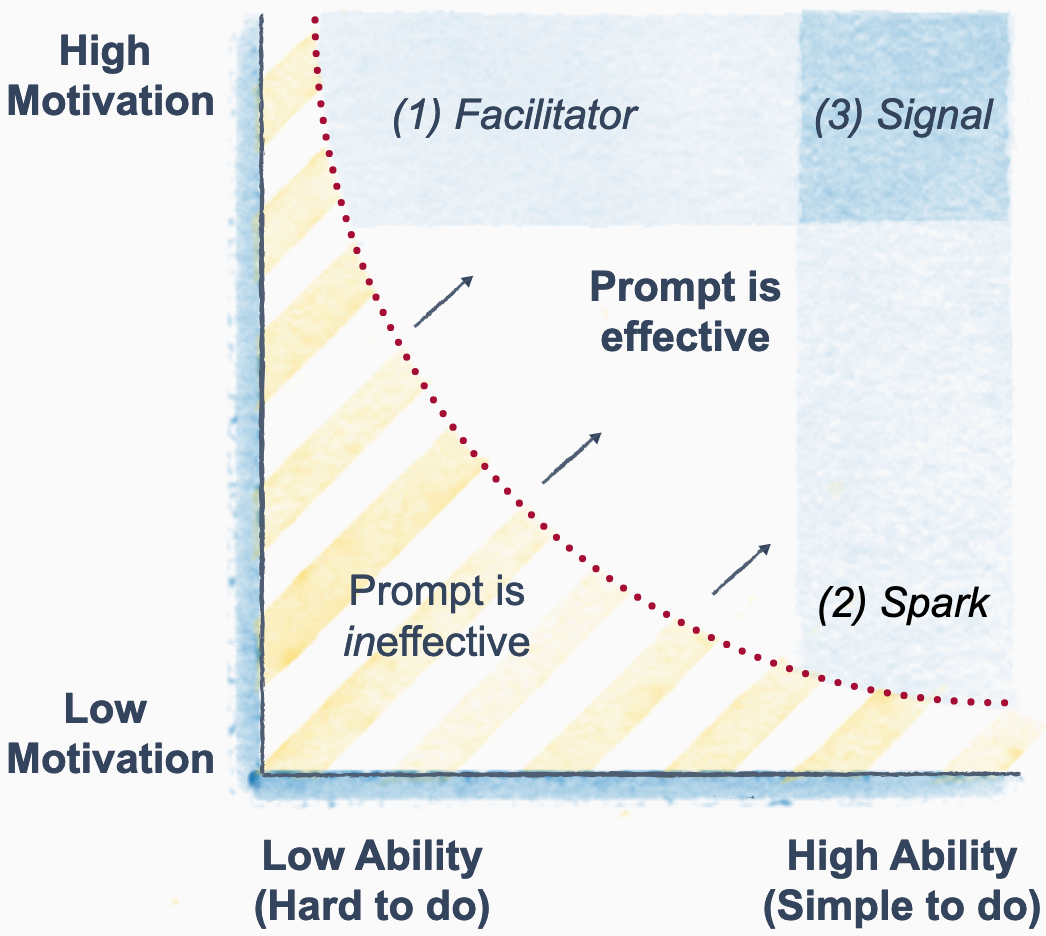

Up to this point, we have discussed improving motivation and ability in terms of moving users over the action line in the Fogg Behavior Model. With users above the action line, you can construct the third part of the equation: prompts.

- Behavior = motivation + ability + prompts

BJ Fogg defines prompts as “cues to action.” They tell a user to perform an action immediately. For example:

- An app might prompt users to stand up from their desks and stretch.

- An email might prompt users to set a weekly time for tracking their expenses.

The call to action is what differentiates a prompt from earlier efforts to build up motivation and ability. To create behavior change, motivation and ability are not enough: You must also instruct users to perform the behavior.

There are three types of prompts in the Fogg model:

- Sparks: These prompts push the user into action while also providing motivation aligned with pleasure/pain, hope/fear, or acceptance/rejection.

- For example, a subscription service centralizes bills and payment methods. Each month, the customer receives a prompt (in the form of a mailed letter, email, or text message) to pay their bills, along with a calculation of how much interest they would pay if they fell behind or missed payments.

- Facilitators: These prompts push the user into action while also making the behavior easier.

- For example, a lifestyle app presents healthy recipes the day before the user’s weekly trip to the grocery store. With a click, ingredients are placed into a shopping list and then forwarded to the store for pickup.

- Signals: A signal indicates that the user should perform the action. Signals are not aligned with motivation or ability because they are simply an instruction (to pay a bill, practice an instrument, or perform any other behavior).

When designing prompts that might improve ability or motivation, you should focus on the positive end of the spectrum whenever possible. Positive reinforcement is more effective in the long term. Negativity is initially powerful, but eventually wears many people down.

As with other complex tools with specific terminology, it is important to avoid getting bogged down in the details, such as categorizing what is a spark, facilitator, or signal. The vocabulary simply helps you note the different goals of these prompts. When you are designing prompts, keep either motivation or ability in mind as your goals.

Review your response to the earlier question regarding possible ways the HealthTips app might increase motivation and ability.

Your response will depend on how you approached the previous question. The following are some examples:

- Original ability-increasing idea: Free healthy snack packs based on users’ interests

- Facilitator prompt: A pop-up advertisement or notification to repurchase a previous order of healthy snacks

- Original ability-increasing idea: Fun illustrations of quick stretches for workers

- Facilitator prompt: A mid-afternoon notification to get up and perform a specific stretch, featuring a fun illustration

- Original motivation-increasing idea: Weekly messages from healthcare professionals that emphasize patience and positive reinforcement

- Spark prompt: A notification for the user to reward themselves for small progress toward a healthcare goal

- Original motivation-increasing idea: A moderated community where people can share stories but avoid exposure to negativity

- Spark prompt: The app sends the user a link to read the replies under their recent post, noting that a moderator has marked it as a favorite

Now that you have attempted to design prompts for both Segment A and Segment B, I would like to highlight some synergy between the tools here. The design heuristics you learned earlier can be productively applied to the prompts in the Fogg model.

When designing prompts, keep in mind that the heuristics can address both motivation and ability. For example, recognize constraints involves considering factors such as time, money, routine, and physical and mental capability. These all impact the user’s ability to adopt a new behavior.

The heuristic provide responsive feedback is beneficial for any prompt. Will users know they have done something positive and feel rewarded? Will they recognize that their ability has increased?

Additionally, minimize perceived complexity and match mental models are particularly useful when evaluating ability prompts. Have you presented these prompts as simply and intuitively as possible? If not, you might be overtaxing the user’s mental resources at a critical moment.

These are just some ways you can use design heuristics to iterate on behavior change innovations. Since the tools here all help you understand user thoughts and behaviors, you can use them simultaneously to answer the research questions you encounter along the way.

Now, review your earlier ideas, as revised to include a prompt or “call to action.”

Recall that the design heuristics presented here are:

- Anticipate needs

- Recognize constraints

- Create responsive feedback

- Match mental models

- Reduce complexity

- Prevent errors

You know that facilitator prompts take advantage of users’ ability, and spark prompts take advantage of users’ motivation. The goal is to create a chain of new behaviors. Even if the prompts start small, they can set off a long chain of cause and effect.

For example, consider Segment A of the Silent Middle. Perhaps they are prompted with a great deal on home exercise equipment in the Health Tips app. They can’t resist, and now the equipment is in their home. Then they are prompted with a list of quick, five-minute exercises in the app. This makes them feel more able and more motivated. One session increases their motivation so much that they start looking for more equipment and exercises on their own.

This demonstrates how facilitators and sparks can interact to create a virtuous cycle. As ability increases, users see results and feel more motivated. This motivation, in turn, leads them to further increase their ability, continuing the cycle. The design firm IDEO describes this kind of cycle as an adherence loop. While the Fogg model and the adherence loop do not use exactly the same vocabulary, the underlying concept is the same: ability, motivation, and knowledge can create a reinforcing cycle.

The takeaway is that you should structure any behavior change innovation with prompts that reinforce each other. Map out a chain of behaviors you would like users to adopt. Then, using personas, the design heuristics, and other tools, ideate on the prompts and experiences that could bring that chain to life.

The Fogg model is one of many behavior-change models. Evaluating ability and motivation is a good starting point, but there are countless social and cultural factors that impact behavior change too. In the following video transcript, Christi Zuber discusses the tradeoffs of analyzing users from simple vs. more comprehensive perspectives.

Note: Christi Zuber mentions the COM-B model, developed by Susan Michie and others. Their model will not be discussed further here, but sources for further reading can be found on the Internet.

And I think of, for example, BJ Fogg’s B=MAT model and then Susan Michie’s COM-B model, for example. So when I look at those two things, there are some complements in those. They talk about motivation. One says abilities, another says capabilities. So there are these elements that are similar.

BJ’s model is a—he takes pride, as he should, in its simplicity. It’s much easier to understand and apply and utilize if you know what the behavior is that you’re attempting to change. It makes it very simple, and simple makes it more accessible and actionable for people. I think that that’s a beauty of his model. And when he breaks it down into things like tiny habits and so forth, I think that those are really wonderful things. And very useful and easy and empowering to do.

When you look at something like Susan Michie’s model with COM-B, that’s a fairly complex model. I mean, I think they took 18 or so different models and synthesized them together and combined them. So there’s a lot of density in her model, which doesn’t make it as accessible as BJ Fogg’s model. Though something that I would say that I do very much value and appreciate about her model is it does take into account more about the environment, about policies and so forth.

So when you’re trying to create a change, if we’re talking about an individual change like getting more exercise or quit smoking, or maybe you’ve created an app, and you want people to do certain things on the app to take some action to or that trigger is coming or so forth, I think BJ Fogg’s model is great for that. When you’re talking about very complex societal challenges, often actually what you’re even trying to change isn’t as clear. It’s almost like a big balled-up strand of Christmas lights.

So for those kinds of situations and when it has a big societal component to it, and you have levers like policy and the context of the environment around you, what’s in it, for example, walking trails and food incentives and various things like that, I think that model is good with helping you to get a much broader perspective of all the potential levers that you might have within a society to create societal changes.

So I think that’s why it’s great to understand and have access to some different models. And that way, you can play around with what’s actually appropriate for what you’re trying to do and look at it through different lenses. Just like in human-centered design, there are many different tools. There are literally thousands of tools that I have in my toolkit for human-centered design. Now, do I use all of them all the time? No. But by having different ones, you can find what works in different situations and play around with them and give yourself a chance to have fresh eyes towards whatever that challenge is you’re trying to solve.