Design Heuristics for Generating and Refining Ideas

Ideate - User Values and Behaviors

Anticipate Needs, Recognize Constraints, and Show Responsiveness

Learning Objectives:

- Identify the first three design heuristics for evaluating solutions

- Explain how feedback improves users’ experience of a design

This is the start of the second series of articles focused on the ideate phase of design thinking. Before we move forward, let’s take a moment to recap where we’ve been so far.

In the Tools and Frameworks for Generating Ideas series of articles on Ideation, we transitioned to ideation by creating design principles. You were introduced to the SIT methodology for ideation, which uses structured thinking tools to generate and refine ideas by breaking cognitive fixedness. This process helped uncover the “voice of the product,” which you could then compare to your design principles in a creative matrix.

We also addressed situations where the root cause of a problem is unclear. In these cases, you practiced creative problem-solving using tools such as inversion, alternate worlds, and brainstorming. The previous series of articles was largely tool-based: you applied the tools and refined the results by judging them against the design principles. This approach started with the voice of the product and then addressed user needs.

In this series of articles in Ideation - User Values and Behaviors, we shift focus to user thoughts and behaviors. By reflecting deeply on user values and behaviors, you can generate valuable new ideas and refine existing ones. In other words, we begin with the voice of the user.

Our first lesson will focus on design heuristics. We will discuss six rules of thumb, defined by the LUMA Institute, for generating and refining ideas. Next, we’ll explore a popular topic in innovation: behavior change. We will examine where your users currently stand in terms of ability and motivation, and how to guide them toward the desired behavior. To do this, we’ll use tools like personas and BJ Fogg’s behavior model.

SIT’s thinking tools for ideation begin with the voice of the product. Some of the other tools there, like 2 by 2 frameworks and brainstorming, can build from either the product or the user. In this series, we will specifically focus on refining ideas based on your research into user needs.

In 2013, Facebook launched Facebook Home, a free app for Android phones.

- Facebook Home replaced your unlock screen with an interactive Cover Feed.

- The Cover Feed displayed updates from Facebook friends. You could comment, like, and scroll through your friends’ updates and photos without unlocking your phone.

- Another feature was Chat Heads—profile icons that appeared on top of the Cover Feed and other apps when friends messaged you. You could quickly tap them to reply and manage conversations.

- Facebook marketed the innovation this way: “If sharing and connecting are what matters most, what would your phone be like if it put your friends first?”

Recall that Function Follows Form encourages us to consider the advantages of an idea before any disadvantages.

Applying the Function Follows Form principle to Facebook Home, what do you think are the potential benefits of this idea, and what might be some challenges?

Some of Facebook Home’s best features, such as the Chat Heads experience, were later incorporated into Facebook Messenger. For huge Facebook fans, the benefits of the idea were clear: You could completely change the experience of using your phone, for no additional cost, and make it more personal.

There were challenges to consider as well. For example, would users be able to customize how active their phone screen was? Let's discuss this challenge related to the perceived lack of control as we introduce a new framework: design heuristics.

Let’s analyze Facebook Home. Which concerns did you identify in the activity above? Perhaps one of them was a lack of control. Control and freedom are fundamental characteristics of a good user experience—often unnoticed until they are taken away.

Consider everything you use your phone for: checking the weather, looking up a recipe, checking a game score, or finding out if a restaurant is open. These are quick, time-sensitive tasks, often performed while multitasking. Facebook Home, however, required users to navigate through the Facebook app to accomplish these actions, adding unnecessary steps and complexity to otherwise simple interactions.

Facebook Home was an interesting idea that could have succeeded under different circumstances. Its performance, however, offers valuable lessons about general principles for innovation. These lessons are encapsulated in design heuristics.

Design heuristics are rules of thumb that refine a design to better respond to user needs. They achieve this by considering users and the context in which they operate, minimizing the cognitive adjustments required to use a product, and anticipating and preventing user errors.

There are dozens of design heuristics available, but in this blog, we will focus on practicing a few of the most common and impactful ones. These principles will help you create designs that are intuitive, user-centered, and effective in their context.

Although the benefits of Facebook Home were not realized in the way they were originally designed, elements like multitasking with multiple apps on screen are now commonplace on smartphones. It is important to continuously evaluate the benefits and challenges of ideas so that you can iterate and improve on core experiences.

Design heuristics are a common tool for this type of evaluation in the innovation world. We will reference some of the LUMA Institute’s design heuristics, but you may find others or develop your own as you learn more about design and innovation.

- Design heuristics are “rules of thumb” that help you keep the end user’s experience in mind while you design.

- Design heuristics are applicable to product, service, experience, strategy, and business model designs.

- Design heuristics are different from design principles, which we defined earlier.

- Design principles answer the question, “What characteristics would a solution need to be successful and user focused?” You can place these principles in the top row of the creative matrix, for example.

- Design heuristics, on the other hand, are guidelines for evaluating and refining ideas from the users’ perspective. While design principles are specific to your user research, design heuristics can be applied to any design problem.

We will focus on six design heuristics:

- Anticipate needs

- Recognize constraints

- Create responsive feedback

- Match mental models

- Reduce complexity

- Prevent errors

The first two relate to needs and constraints that may affect users. The remaining four heuristics go deeper into user expectations, perceptions, and mindsets.

Together, these design heuristics give you a well-rounded list of ways to empathize with users and consider how they might experience an idea.

Our first design heuristic is anticipate needs. By now, you’re familiar with this concept and the AEIOU tool, which helps you anticipate needs from multiple perspectives—not just who the target users are, but also how they will use the innovation, where they will use it, and other contextual factors.

Let’s explore how broad the term “needs” can be. For example, it includes the need for control. Consider Facebook Home again, which covered the home screen with a social media feed. This raised a key question: What are the trade-offs between providing easy access to Facebook and preserving the user’s sense of control? Could additional features or testing better address the user’s need for control?

In other contexts, user needs might also include flexibility and accessibility. Once you’ve identified your potential users, you can evaluate how each feature accommodates different accessibility needs. For example, will a novice feel as comfortable using the product as an expert? Is flexibility important to the design of your innovation?

These are just a few of the user needs you may want to consider as heuristics for refining your innovation’s design. While heuristics can spark new ideas, they are equally useful for cross-checking ideas developed with other tools. The more you iterate and refine during the ideation phase, the better prepared you’ll be to combine ideas and move into prototyping later.

As you’ll learn in the develop phase of design thinking, small, rapid tests are essential to an innovation’s success. Therefore, it’s valuable to apply a design heuristic like anticipate user needs even after the clarify phase. Better yet, have another person or team review your idea through the lens of design heuristics.

The ultimate goal is to strengthen your idea as much as possible before implementation, ensuring it is robust, user-centered, and adaptable.

Anticipate needs: Consider user needs from multiple perspectives, considering the characteristics of possible user groups and the context of use, including how, where, and when they will use the innovation.

Earlier, we explored several innovations that T-Mobile introduced as part of its customer-focused business strategy:

- No annual service contracts

- The ability to trade in and upgrade your phone

- No roaming charges

- The Team of Experts: customer service teams assigned to specific customers

- T-Mobile Tuesdays: Offers and deals for customers on every Tuesday

Choose one of these innovations and explain how it anticipates users’ needs. Do you believe it could be modified to serve these needs even better? How?

The “anticipate needs” design heuristic connects closely to the pain points you identified in user research. It also encourages further ideation by asking you to refine ideas through a user lens.

The following are some possible responses to the preceding questions:

- No annual service contracts, no roaming charges, the ability to upgrade your phone:

- Users need to feel in control of their devices and their partnership with T-Mobile. These innovations make the customer feel trusted and in control. T-Mobile might strengthen these ideas even further by creating additional opportunities to opt in or opt out of services.

- The Team of Experts and T-Mobile Tuesdays

- Users need to feel connected to their mobile provider. These innovations cultivate a personal connection and rewarding feelings. T-Mobile might strengthen these ideas by applying attribute dependency: What if there was a connection between length of participation and the rewards available?

Let’s move on to the second design heuristic: recognize constraints.

The user’s context will often introduce constraints that limit the range of potential design ideas. For instance, if target users need to rely on an app in areas with limited access to electricity, you have to consider the energy implications of every feature that you add to the app. This is an example of addressing a constraint in design.

Imagine you are developing a subscription meal service that introduces customers to dishes from around the world. Each month, customers receive a box of ingredients, a recipe, and a glossy pamphlet giving a history of the dish.

Which of the following user constraints do you think would be most important to address?

- Dietary preferences

- Delivery coordination

- Cooking tools and appliances available to users

- Users’ culinary skill levels

You may find overlap between user needs and constraints: The purpose of providing two separate categories is to prompt exploration from multiple angles—not to get caught up in debates about classification.

The implementation of the Jaipur Limb by BMVSS is an excellent example of an organization taking user and environmental constraints into account when designing a service model:

- Patients have no access to phones or internet and cannot make appointments, so security guards are able to admit patients whenever they arrive.

- Patients have little to no money to pay for the limb or the fitting, so BMVSS provides its services for free and relies on donations rather than patient fees to support its work.

- Patients have a short window of time to spend away from work and family, so the fitting of the limb takes place in as little time as possible.

Some of these “constraints” could also have been listed as “needs.” This actually gives us insight into a core design problem for BMVSS: patient access, and how to expand that access in a sustainable way. Their solution had to take user constraints into account if it was going to be implemented and be useful.

In most design situations, constraints will be different from needs. Consider this example related to process management:

- Employee need: The employee requires empowerment to respond quickly and effectively to the latest information.

- Employee constraint: The employee is not empowered because of senior management concerns about inefficiency and lack of controls.

- Innovative solution: Request empowerment within defined limits or boundaries and consistent with the organization’s values and beliefs.

Now that we have discussed two broad design heuristics, let’s shift to more specific ones. A third design heuristic is create responsive feedback. We’ve all experienced the frustration of not knowing if something is working. You push a button, nothing happens, and you’re left wondering if you made a mistake. This is a common oversight in product development, but responsiveness applies to services, models, strategies, and other types of innovation as well.

For example, imagine walking into a busy new restaurant with no clear indication of where to pick up your takeout order. As a design heuristic, create responsive feedback means thinking about how the innovation will communicate with the user. How will users know their actions have been successful? The product, service, model, or strategy should clearly and easily provide status information.

The LUMA Institute emphasizes the importance of showing users the effect their actions have on the system. If the result isn’t instant, users should at least understand where they are in the process and have an idea of how long it will take to complete. For instance, modern pedestrian crossing lights often include both audio and visual cues to indicate the button has been pressed. Previously, pedestrians might press the button multiple times to ensure it worked, and those with visual or hearing impairments might struggle to know when it was safe to cross. Now, these devices clearly communicate changes in traffic conditions.

Even small examples, such as your smartphone vibrating when you send a text message, provide positive feedback that the action has been completed. Quick responsive feedback has become essential in digital strategies. For example, target.com has optimized its website to respond to customer queries in milliseconds. Without this immediate feedback, customers may feel uncertain about whether the system is working and might abandon their shopping experience altogether.

Create responsive feedback: Inform users of the effect their actions have on the system. The innovation should communicate status information clearly and easily, including how long a particular process might take to complete. It should confirm that users have performed an action successfully, or notify them if they have not.

What are some other examples of responsiveness built into the design of a product, service, strategy, business model, or other innovation? How do they improve the design?

The following are all examples of responsive feedback that make innovations more user focused:

- Circles spinning to indicate that a website is processing information

- A bar filling up as computer software installs or updates

- Emails sent when orders are processed and shipped

- Text-message reminders for appointments

- Digitization strategies, such as alarm systems that provide feedback over a cell phone about the safety status of a property

Responsiveness is also about maintaining the user’s engagement with a product, service, business model, or strategy. T-Mobile’s promotion T-Mobile Tuesdays was created from an analysis of customer journeys with the company over the long term. It is a good example of how responsiveness can improve user engagement and build a brand.

The introduction of a recurring positive response (based on T-Mobile membership) reinforced customers’ belief that the relationship was working for them.

T-Mobile Tuesdays was born from the idea that every Tuesday, every single customer deserves a heartfelt thank-you from T-Mobile. This thank-you comes in the form of something free, a discount, or another valuable offer. In their very first week, the offering was a free pizza from Domino’s—and the response was overwhelming. Domino’s experienced supply chain issues, and they ended up closing most of their fleet due to the sheer demand. That’s when they knew they were onto something big.

Years later, they’ve partnered with major brands across various industries, all eager to work with them to thank their customers. Of course, there’s value for those brands as well, and their customers understand that. But T-Mobile Tuesdays isn’t just about discounts, coupons, or gimmicks. It’s about providing something of genuine value to their customers—not just once in a while, but every single week.

This program is a reflection of who they are as a company. It’s a way to show that they’re different, with a mindset focused entirely on the customer. It’s a demonstration of their commitment to customer-centric thinking and the value they place on their loyalty.

Think about the following service: An automated check-in desk is available for guests at a hotel. It offers emailed receipts and a virtual receptionist to confirm actions and answer questions.

In what ways does this service meet the three design heuristics we have covered so far? If you feel a heuristic is not completely addressed, note one possible way the service could be improved.

The following are some possible answers:

- Anticipate Needs: An automated check-in desk provides 24-hour service and quick, transparent payment options. This anticipates the needs that guests may have at very late hours, such as immediate and private service. Some demographics may prefer a kiosk to an in-person interaction.

- Recognize Constraints: Constraints include concerns about security and the need to account for various problems. The virtual receptionist can anticipate some of the most common guest questions, but it would need to be designed carefully to avoid frustration. How will the desk balance ease of use with these constraints to provide a satisfying experience? Consider spacing automated check-in desks apart and running a trial to learn where guests encounter problems.

- Create Responsive Feedback: The automated desk may provide receipts, keys, and answers to common questions. This will be an important heuristic, however, especially in hotels where higher levels of service are expected. Feedback must be clear at every step to ensure that this does not seem like a downgrade from traditional in-person service.

These are example thoughts: The goal is not to create an exhaustive list of pros and cons, but rather to focus your thinking on specific aspects of the idea, and create topics for group discussion and ideation.

Match Mental Models, Reduce Complexity, and Prevent Errors

Learning Objectives:

- Identify and explain the final three design heuristics

- Apply the heuristics to an example design

To explore the fourth design heuristic, “match mental models,” let’s begin by discussing Uber’s ride-sharing business.

There are many possible answers to the preceding questions, but the concern we will focus on now is trust and security. A main concern for Uber was this: Would potential riders feel comfortable getting into someone’s car? This leads us to the fourth design heuristic: match mental models.

- Match mental models reminds innovators to leverage users’ understanding of the world, and to not force them to adapt to an unnatural system.

- For example, certain images are widely accepted as shorthand for concepts like play and pause.

It would be ineffective to create a “play” button with a new shape. If you must break from existing mental models, there should be a good reason that offers improvement in usability.

Similarly, there were established mental models for professionalism in the transportation world when Uber was designing its model.

Uber’s first offering was a black-car service—what would eventually become Uber Black. It not only tested users’ response to the concept of using an app to hail a ride, but also reassured them about quality and safety: The black exterior and interior of the luxury cars and the formal attire of the licensed for-hire drivers connected to users’ mental models of limousine service, which was associated with professionalism, luxury, and safety.

Later, Uber introduced non-luxury vehicles, and allowed everyday people to sign up as drivers using their own personal vehicles (provided they met certain standards). This is an excellent example of gradually experimenting with an innovation to see what works and what doesn’t. By launching with the black-car service first, the founders were able to remove the variable of safety concerns so they could better learn how users responded to app-based ride-hailing as a concept.

To introduce the final two design heuristics, “minimize perceived complexity” and “prevent user errors,” let’s explore another example:

Again, there are many possible answers to the preceding questions, but we will focus on one concern from the time: users’ willingness to take on the difficulty of assembly.

IKEA had developed a brilliant strategy based around flat-packed, unassembled furniture. An important factor in this strategy’s success was users’ ability to assemble the furniture without frustration.

If the experience was too frustrating, some customers would think the hassle wasn’t worth it: They might be willing to pay more to receive assembled furniture from a competitor. The final two design heuristics on our list would be especially helpful to designers in this situation.

- The fifth design heuristic is minimize perceived complexity. Products and services should be self-evident in design. They should not burden the user to figure them out, but be as easy as possible to use and understand.

- The sixth design heuristic is prevent user errors. Do as much as possible to lower the possibility of user errors. When there are errors, provide opportunities for a graceful recovery.

Think about a product or service you know, or choose one of the hypothetical example options that follow.

Example options:

- A new service at the post office asks customers to do their own weighing, form completion, and drop-off

- A new app asks users to select up to five short stories of their choice to combine into a personalized print book

The following are some ways you might apply the design heuristics to the example options. Note that some ideas may meet both heuristics (“reduce perceived complexity” and “minimize chance of errors”), though they are listed only under one category.

- A new service at the post office asks customers to do their own weighing, form completion, and drop-off

- Reduce perceived complexity:

- Provide a digital scale with a simple, easy-to-understand readout

- Provide an illustrated overview of all the steps in the process, and clear instructions for each step

- Provide separate stations (areas) for each step, and use arrows or numbers to guide users from one to the next. Or, guide users through the process interactively, e.g., using an iPad app

- Minimize chance of errors:

- Provide a “frequently asked questions” document

- Post a sign by the scale telling users to make sure they are using the correct measurement system (e.g., metric vs. US customary units)

- Reduce perceived complexity:

- A new app asks users to select up to five short stories of their choice to combine into a personalized print book

- Reduce perceived complexity:

- Provide an intuitive, searchable catalog of all short story options, and allow users to sort by genre, author, or year of publication

- Minimize chance of errors:

- If some stories or features have additional costs, allow users to set a budget, and warn them ahead of time about choices that will surpass that budget

- Allow users to preview their custom covers or fonts to make sure they appear as intended

- Provide friendly warnings about authors or stories that are often confused (e.g., those with similar names or topics)

- Reduce perceived complexity:

These two design heuristics—make it simple and prevent mistakes—may require the most empathy of all. As the creator of an idea, you’ve likely spent weeks or months developing and testing it. How can you imagine it not working? It’s a challenge to approach your innovation as if you knew nothing about it.

To effectively apply these heuristics, you may need tools that help you identify user contexts and pathways, such as the AEIOU framework, journey maps, and personas, which we’ll cover soon. These tools allow you to anticipate the difficulties a user might face.

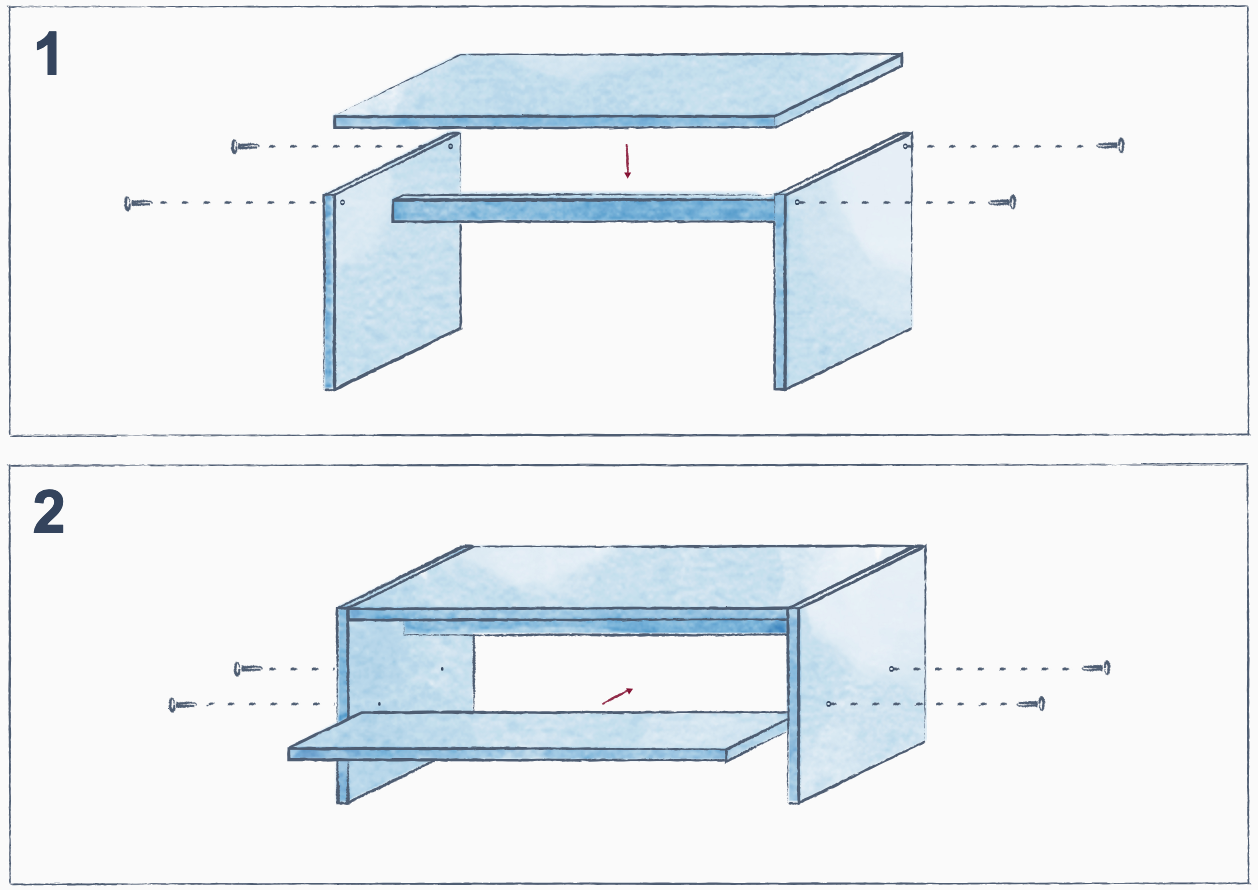

Consider IKEA as an example. To minimize perceived complexity, IKEA made two key design choices for furniture assembly. First, they include simple tools with their furniture. These tools are easy to identify and use, ensuring that customers have everything they need. Second, IKEA provides clear, step-by-step illustrations for assembly. These instructions contain no words, relying solely on visuals. By doing this, IKEA forced its designers to present assembly instructions as clearly as possible and to design with simplicity in mind.

Assembling something like a wooden dresser is inherently complex, yet IKEA’s approach makes it feel manageable. By breaking the process into simple steps and providing intuitive tools and instructions, IKEA creates the impression that anyone can successfully complete the task.

In addition to designing to minimize perceived complexity, IKEA also designs its furniture to prevent errors. Furniture pieces are created in such a way that pieces will not fit if a user tries to arrange them incorrectly. In this way, the furniture is “designed for easy assembly.” Even if customers make a mistake, the pieces won’t let them proceed.

If the furniture’s design and clear instructions do fail, IKEA provides users with a way out: an illustration reassuring users that they can call IKEA and ask for help if the instructions are not clear enough, or if they have any other questions. This is what the “prevent errors” design heuristic means by the expression “provide for a graceful recovery.”

IKEA’s simple, illustrated style for user instructions is now widely imitated.

Through the human-centered approach to development, organizations are becoming better at anticipating and preventing user errors. For example, when you click Send in email programs like Outlook and Gmail, the message will be scanned for variations on the word “attached,” and the program will stop and give you a warning message if you have not attached a file.

In such cases, the error is prevented—if this has ever happened to you, you may have even thanked the program! That is the ideal response to innovations that meet this heuristic.

Remember: User errors are inevitable. However, by applying design heuristics, you can anticipate certain errors and make them impossible to do or provide users with the least frustrating method of solving them.

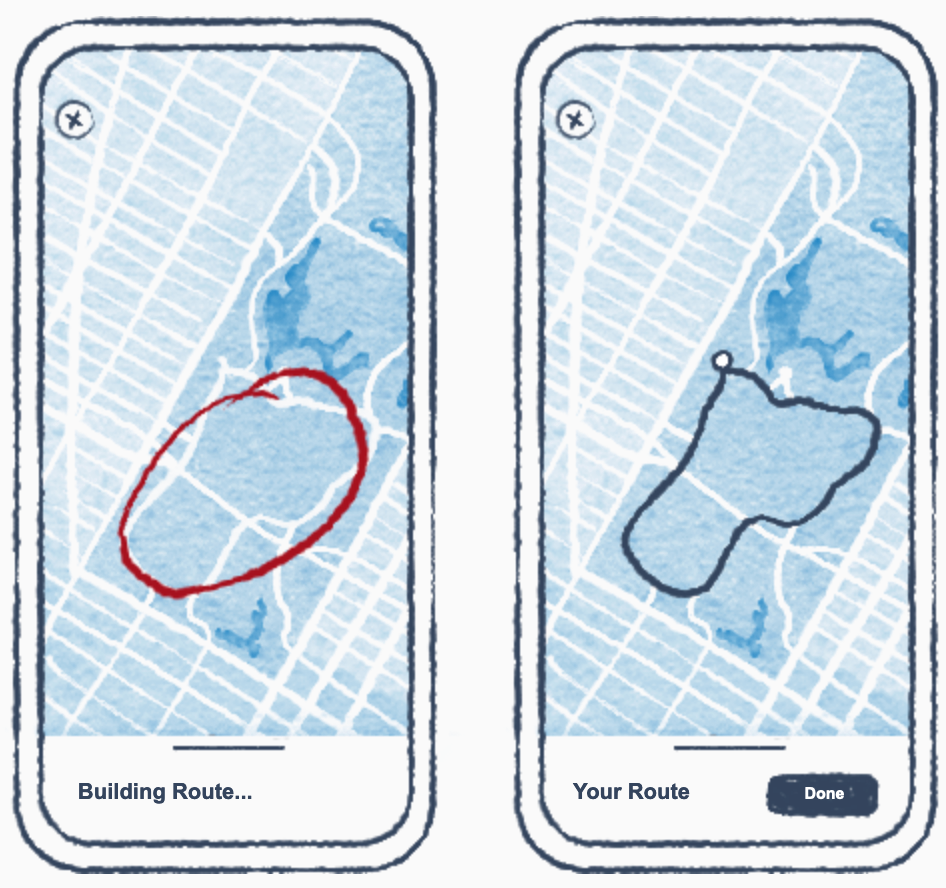

Strava is a workout tracking app and social network that allows users to track their progress, routes, and equipment, and compare their exercise results with others on the network.

For example, for runners, the app can connect to a smartwatch, and at the end of the running session, it can process the data from the watch and show visual and other information about their run, such as the route, average speed, and other factors.

There is also connectivity with other apps, like Google Maps: As demonstrated in the images that follow, you can trace a running path on the map with your finger, and the app will plan a route along that path.

- Anticipate user needs to account for different user types.

- Account for user and environmental constraints.

- Create responsive feedback.

- Match mental models to leverage users’ understanding of the world.

- Minimize perceived complexity to make it easy for the user to use the product.

- Prevent errors and provide for a graceful recovery.

Do you recall the Function Follows Form principle from the previous articles? It was a key part of the SIT methodology. This principle states that after generating an idea, you pass it through marketability and feasibility filters to assess its benefits and challenges. You then use the results to iterate and refine the idea.

The design heuristics function similarly. Whether you already have an idea or are trying to generate one from the existing context, you apply the heuristics and observe what happens when you adjust the virtual product to make it more user-focused. This process creates a cycle of divergent and convergent thinking: you brainstorm possibilities, critique them, and see what new ideas emerge from the critique.

Keep in mind that we are still in the ideate phase of design thinking. The goal is to generate as many options as possible. Don’t think of the design heuristics as tools for narrowing possibilities—that will come later in the develop phase when decisions about the final innovation are made. The value of these heuristics lies in their ability to provide a quick starting point for focusing your thoughts. For instance, “How can we improve this idea?” is a broad and challenging question, but “Does this idea truly address users’ concerns about control?” is more specific and easier to discuss productively.

By applying these user-focused guidelines early, before prototyping, you’re more likely to identify and address errors before investing resources. Next, we’ll examine a real-life example of an innovation where applying design heuristics could have significantly improved the outcome before implementation.

Case Study: The PlayPump

Learning Objectives:

- Evaluate the assumptions behind a design and explain possible negative outcomes

- Apply the design heuristics to generate alternative solutions for a design

You have now learned all six design heuristics that we will cover here. The best innovations will:

- Anticipate needs

- Recognize constraints

- Provide responsive feedback

- Match mental models

- Minimize perceived complexity

- Prevent errors

If you are looking for opportunities for incremental innovation, try applying these heuristics to your existing products, services, business models, strategies—even how you work on innovation. They will help you identify areas where a user focus is missing, and therefore provide more opportunities for applying the tools from the clarify and ideate stages of design thinking.

Design heuristics are also useful when you are reviewing the desirability of the innovations you are currently developing. To demonstrate how these heuristics might improve the user focus of an idea, let’s examine the PlayPump, an innovation that briefly captured media attention in the early 21st century.

The following video transcript, originally produced by PBS Frontline in 2005, describes the PlayPump in the early stages of its rollout.

AMY COSTELLO: In many parts of the world, it is impossible to find clean drinking water, especially here in South Africa, where some 5 million people have no access to safe water. But one man is trying to do something about it.

TREVOR FIELD: We’re going towards an area called Stinkwater. It’s a lovely name. And that’s obviously an Afrikaans name. And the reason why it’s called Stinkwater is because the water stinks.

AMY COSTELLO: Trevor Field is obsessed with solving South Africa’s water problems. He took me to Stinkwater to show me what he’s up against. Here, people get their water from leaky, contaminated hand pumps, and the work involved is exhausting.

AMY COSTELLO: How’s that feel, Trevor?

TREVOR FIELD: Hey, man, you don’t need to go to a gym, hey? You can cancel your subscription to Virgin Active. You just do this for a couple of hours a day, and every day.

AMY COSTELLO: Once they’ve pumped the water, women still have to walk long distances back home carrying water on their heads or in wheelbarrows. Each container weighs about 40 pounds.

TREVOR FIELD: You try picking one up. Those are full.

AMY COSTELLO: Yeah, that’s heavy.

TREVOR FIELD: OK, now put it on your head. Off you go. The amount of time that these women are burning up just collecting water when they should be in their homes looking after their kids, teaching the children, just being loving mothers, you know what I mean? What women should be doing, not beasts of burden. Hi, guys!

SPEAKER 1: Hello.

TREVOR FIELD: How are you doing?

AMY COSTELLO: Trevor is an entrepreneur who made his money in the advertising business, and at the age of 42 decided he wanted to give something back.

He teamed up with an inventor, and the roundabout outdoor play pump was born.

TREVOR FIELD: Yeah. So what happens is as the kids spin here–and it doesn’t matter which direction they go; it works in both directions–water is pumped from an underground borehole. It comes across here underground, into this pipe. And not only can you hear the water going into the pipe, you can actually feel that it’s getting very cold.

AMY COSTELLO: Cold, yeah.

TREVOR FIELD: And then from there, there’s an outlet pipe, and it goes across to that tap. When you turn it on, you just get cold, clean, fresh drinking water coming out of there.

AMY COSTELLO: The PlayPump costs only $7,000 to install and can pump up to 400 gallons an hour.

Trevor installs most PlayPumps at schools, where jungle gyms and swing sets are rare. The principal says it’s a hit. It’s fun, and the water’s better, too.

AMY COSTELLO: So this used to be your drinking supply?

PATRICIA MAHOLE: Yes.

SPEAKER 1: This is where you would drink water from.

PATRICIA MAHOLE: Yes.

AMY COSTELLO: So, what do we have here?

AMY COSTELLO: Patricia Mahole, a teacher, says for years, they never realized the groundwater here was polluted.

PATRICIA MAHOLE: We thought it was safe, but the kids used to get diarrhea and vomit, get sick.

AMY COSTELLO: The PlayPump changed everything by drawing clean water from deep underground.

PATRICIA MAHOLE: We used to stay here for nearly the whole day and night, and go to sleep very late looking at this pump, playing there, looking at the kids when they play there. It was just a nice thing.

AMY COSTELLO: Trevor sells ad space on the water tanks and uses the money for maintenance to keep the PlayPumps working.

The PlayPump is a piece of playground equipment for children, but it is also a tool that fulfills a community need.

As the video transcript illustrates, children are the “users” of the pump, though they perform this task differently than the women who usually pump water. Children are eager to play with the new toy and having no trouble generating enough energy to pull water from the ground.

The pump’s design is a good example of the task unification tool from the previous articles: assigning a task (pumping water) to an existing resource (children who would like to play). The program appears to fulfill critical needs.

However, the designers of the PlayPump were making several assumptions about both the children and the PlayPump itself.

There are numerous assumptions to consider related to the PlayPump and the service model around it. The following are examples and not a comprehensive list:

- The advertisements would generate revenue, even in remote areas.

- Children would not become bored with the PlayPump.

- Children’s effort would always be enough to generate adequate amounts of water.

- Adults would have no difficulty exerting the same effort as children on the PlayPump.

- Pump maintenance in remote areas would be quick—and people wouldn’t lose faith in the PlayPump if maintenance efforts took a long time.

- All communities would prefer the PlayPump design over others, despite cultural differences and varying historical reasons for water scarcity.

The PlayPump received a lot of positive initial feedback and high-profile celebrity fundraising. It was therefore easy for designers to assume that they were headed in the right direction.

However, if you apply the LUMA design heuristics to the PlayPump, you can imagine several ways in which it might not meet user needs, address constraints, provide feedback, match mental models (for adults), reduce complexity, or prevent errors.

In reality, the situation diverged from the founder’s assumptions in several key ways. For instance:

- Anticipate user needs - Many of the pump users were older women who often had difficulty using the pump. Could an additional interface for different users be added?

- Minimize perceived complexity - The product was quite simple to use when operated in the intended manner (that is, by children playing). However, for adult users working alone, especially those who were older or ill, the pump made getting water more difficult. Again, could you multiply the methods for drawing water, while providing simple illustrated instructions?

- Prevent errors (and provide for a graceful recovery) - When the product broke down, resources were rarely available for prompt repair. This created a shortage of water, for up to six months in some areas. Could the design be altered to temporarily maintain functionality in the event of routine breakdowns?

Just as looking for unmet user needs can open opportunities for innovation, applying a critical lens to your design ideas can strengthen them. It is extremely valuable to imagine possible future failures from a user perspective, which is one thing that design heuristics allow us to do.

In the case of the PlayPump, the problems with the design began to add up, and the PlayPump project was halted a few years after it began. The following video transcript is PBS Frontline’s 2010 follow-up to their initial report:

AMY COSTELLO: I’m back in Mozambique. I’d heard that the PlayPump rollout had run into trouble, and I wanted to see what had happened. This is the site I’d visited with Trevor Field on my last trip here.

So we’re back here at Intaka Primary School, a few years after we first visited. And if we look over at what’s happened at the PlayPump now, the children are just kind of standing idle. The boy pulls the lever, but no water comes out.

AMY COSTELLO: The assistant principal tells me there’s a problem.

AMY COSTELLO: With no water in the tank, one group of children has to spin in order for others to drink. The PlayPump was supposed to be fun, but this looks like work. And when the water finally comes, the kids battle over it.

AMY COSTELLO: I decided to visit more PlayPump sites. The next one was in a more remote part of Mozambique, with not nearly as many children around. I’d heard this village used to get its water from a hand pump, but then some people arrived to install a PlayPump.

AMY COSTELLO: When the PlayPump came, were you expecting it? Had anybody told you that we’d like to bring a PlayPump to this community?

AMY COSTELLO: Regina showed me how she managed to use the pump, which was designed for children. But she’s young.

AMY COSTELLO: You can’t use it. Can you use it?

AMY COSTELLO: And these women have a bigger problem.

AMY COSTELLO: Regina says this PlayPump hasn’t produced any water for six months. Trevor Field’s plan to cover maintenance with revenue from billboards wasn’t working here. And when the women called or texted the repair line, they told me they got no response.

AMY COSTELLO: I met with Joaquim George. He’s with Mozambique’s Rural Water Authority.

JOAQUIM GEORGE: Once pump break, and we’re taking more than three months to repair, people in this community no longer trust the PlayPumps because they are demoralized, does not work properly. We know it is for free, but does not work properly.

AMY COSTELLO: I asked George about a report the government commissioned on the PlayPump that was never released. It was based on visits to more than 100 sites and detailed a long list of problems like the ones I’d found: the strange operation technique for women, pumps out of commission for up to 17 months, and maintenance, a real disaster. Perhaps most concerning, they found children not really using the PlayPump in the way that it had been touted, something I’d seen for myself at Intaka Primary School.

The following are possible answers to this question:

- Clarify: The creators could have acquired more insight into various users and the context of the community by observing the existing water pumps in use, asking users about their water habits, and exploring different pump options themselves (Look, Ask, Try).

- Ideate: There were many unanswered questions related to feasibility and viability, including issues with sustainability, methods and models for maintenance, and user communication options. You could explore alternate worlds related to maintenance, or apply the SIT tools to a closed-world inventory of the supply chain and maintenance infrastructure.

The PlayPump is such a fascinating case because the idea was so promising, and it was serving people who truly needed help. You may have come up with several interesting ideas for redesigning the PlayPump. Let’s briefly explore some here.

One of the main problems was maintenance. If the PlayPump broke, no one was around to fix it, and requests for repair went unanswered. Perhaps the designers could have created something that took slightly longer to install and had a slightly higher upfront cost but required less maintenance. The influx of large celebrity donations was certainly an opportunity to consider these kinds of changes to the design. For example, could they have trained individuals within the community to help maintain the pumps and provided the necessary materials to do so?

Whatever the solution, it might have come from ideation focused on anticipating needs, recognizing constraints, and preventing user errors. The SIT thinking tools are another avenue for addressing this problem. What if they multiplied components that drew water from the ground, with a qualitative change that made them look and function more like traditional pumps? This might better align with adults’ mental models of how the pump should look and operate.

These are preliminary ideas, and I hope you can see how the shortcomings of the first design didn’t need to be the end of the PlayPump. A careful understanding of the pain points and a fresh perspective on the true problem framing might have led to a more viable solution.

In design thinking, we learn much from failure. This is what some innovation leaders mean when they say “fail fast.” Failing early in the innovation process, when the stakes are lower, can be advantageous. Implementing a culture of learning from failure only works if organizations iterate on ideas before committing enormous resources to implementing them at scale.