Design Thinking & Innovation

Design Thinking and Innovation unlock hidden potential, transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary through creativity and empathy.

Design Thinking is a user-centered approach to problem-solving that involves understanding the needs of users, generating creative solutions, and iteratively testing and refining ideas. It is called Design Thinking because it draws from the designer’s toolkit, focusing on empathy, ideation, and experimentation to tackle complex challenges creatively and effectively.

Innovation sparks transformative change by turning groundbreaking ideas into reality, revolutionizing industries and reshaping the future.

Whenever we ask, "What is the most innovative product you've seen?" we often hear about recent innovations, especially the iPhone or the Internet. These are good answers, but they also represent recency bias. For example, writing and the wheel are equally good examples of innovation. And innovation isn't limited to products or goods. It can also be a service or a business model.

For example, ride-sharing services like Uber and Lyft are innovations. So are models for delivering courses through an internet connection. In manufacturing, there's the assembly line, just-in-time production systems, and total quality management. Digitization has also led to new ways of reaching customers and providing services, such as online banking and online retailing. Language was a very big innovation, maybe bigger than any of the others we've just mentioned.

We don't think about these examples now because we look at our surroundings through the framing of the status quo. The framing is different, and this is very important in innovation. How do you change your perspective on what is possible and what isn't? You'll quickly go down a confined path if you do not. But before we discuss framings, we have to define what innovation is.

We will keep things simple and define innovation as a product, process, service, or business model that has two characteristics: it's novel and it's useful. In other words, for something to be innovative, it has to be new, and it has to offer value to the user. We all know that offering something new and different is important, but it's simply not worth the resources to pursue something that people can not or will not use. An innovation should simply be both novel and useful to some degree.

We characterized an innovation as something useful. Let’s explore what this means. Consider an innovation that you use in your everyday life (such as your phone or online shopping). Can you list some qualities that make this innovation useful?

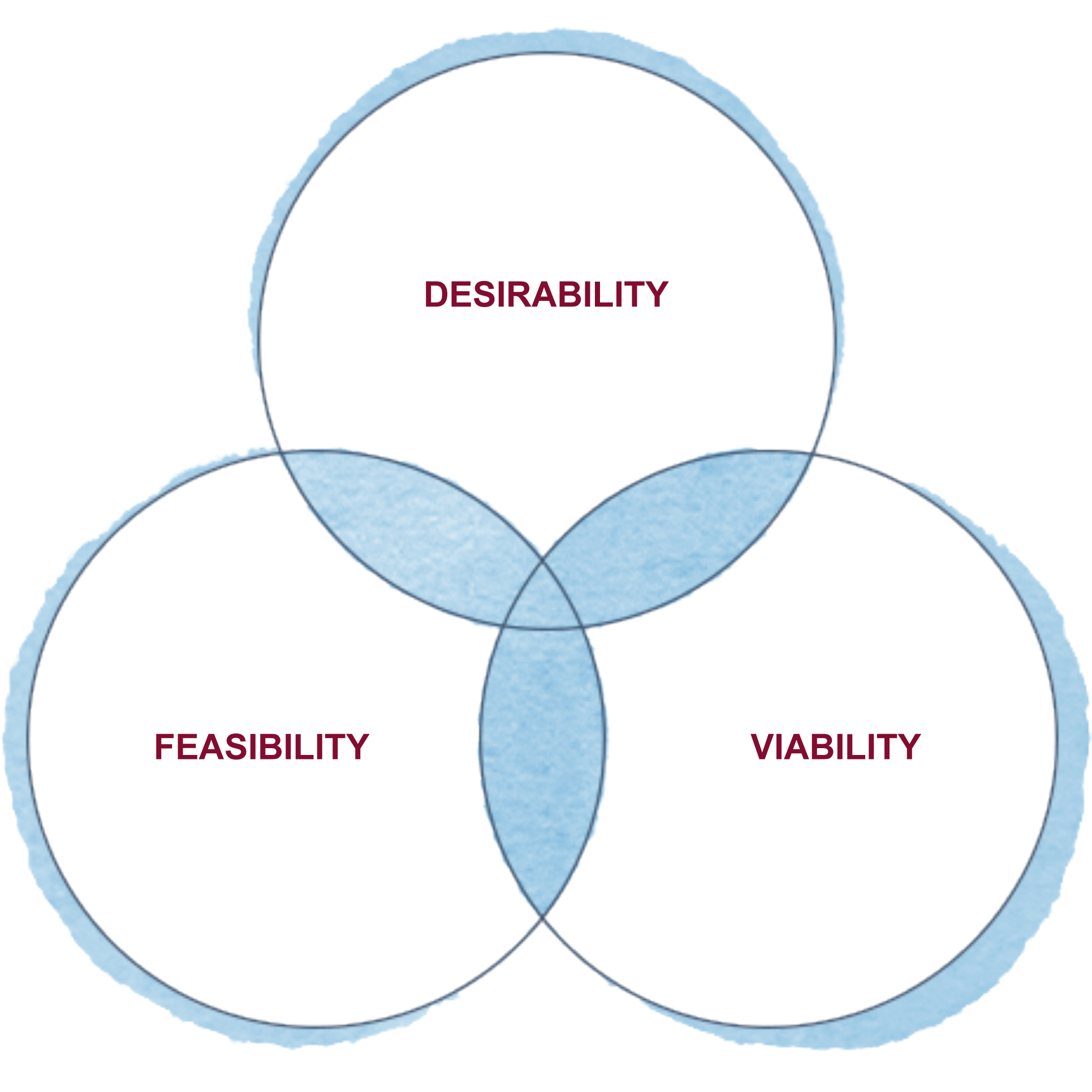

In your response to the previous question, you may have listed characteristics that made the innovation useful to you personally, as a consumer. For a broader definition of usefulness, consider the three characteristics of human-centered design: desirability, feasibility, and viability.

- Desirability refers to what people want or need. It asks:

- Is there a market for this innovation?

- Feasibility refers to what is technically or functionally possible. It asks:

- Can we produce this innovation? Are the materials available? Will laws and regulations allow it?

- Viability refers to the innovation’s economic sustainability. It asks:

- Can we continue to produce or deliver this innovation over a long period of time?

- Can we offer this product profitably by capturing some of the value that is created?

Many attempts at innovation fail because they do not sufficiently address all three characteristics.

We will explore desirability in more detail. It may seem like the simplest of the design characteristics, but it can be one of the most difficult to pin down. Users and customers often don’t know what they want. (if they did, they would ask for it)

Many famous innovations, like the iPod, address latent needs - the needs that users have difficulty expressing and may not even be aware of. The tools will help you practice uncovering those needs and clarifying your approach to producing something desirable. Let's see some example:

- iPod music player

- Explicit: Difficulty bringing physical media (CDs, etc.) on commute or during travel; needing to start up a computer to listen to MP3 files

- Latent: The psychological comfort of carrying around an entire music library - the right music for any moment, including when exercising

- Meal kits delivered by mail

- Explicit: Lack of time and/or skill to cook, reliance on fast food and premade meals

- Latent: Satisfaction of cooking or learning to cook

The goal of the early innovation process is to conduct research, observe users, and inquire into these latent needs: if you don’t know what users really want, you will have difficulty creating something truly desirable.

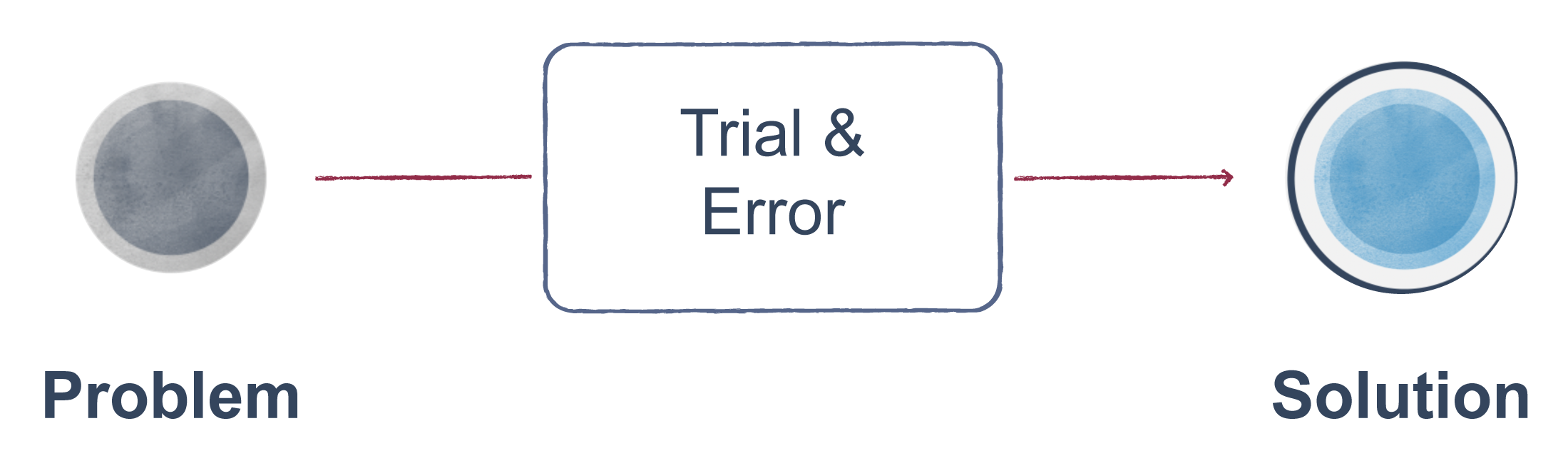

How did the creators of these innovations come up with their solutions? Was it luck or genius? Surely, some innovations were created in these ways, but innovation is not always the result of someone focusing intently on a problem, becoming inspired, and enthusiastically pursuing this fully formed idea.

This trial-and-error approach can work for simple problems, but innovation is rarely a simple problem, especially in the modern world. In the long term, using “brute force” to solve complex problems is inefficient and unsustainable.

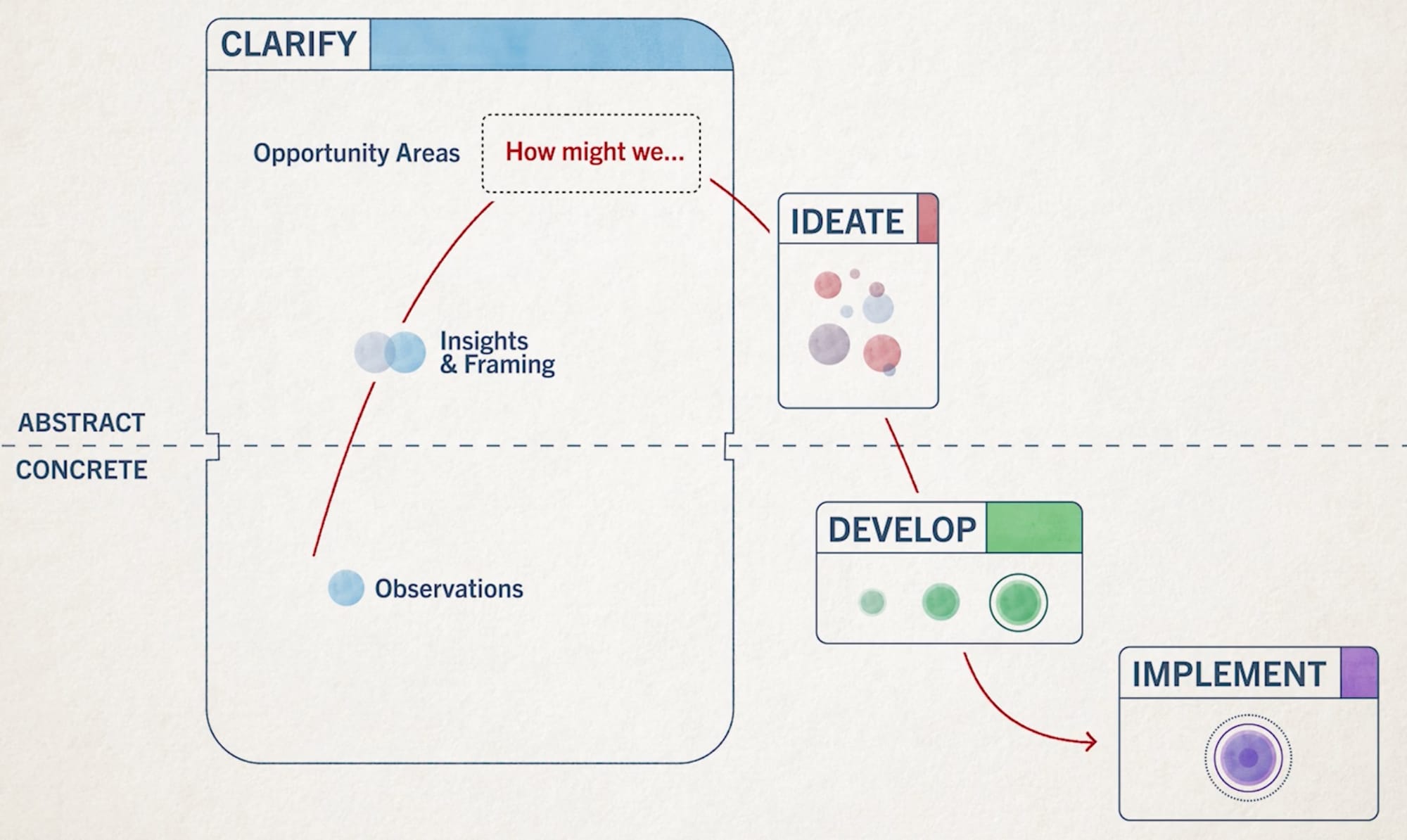

We will use a more structured and sustainable approach. Four phases of innovation will provide the structure:

- Clarify

- Ideate

- Develop

- Implement

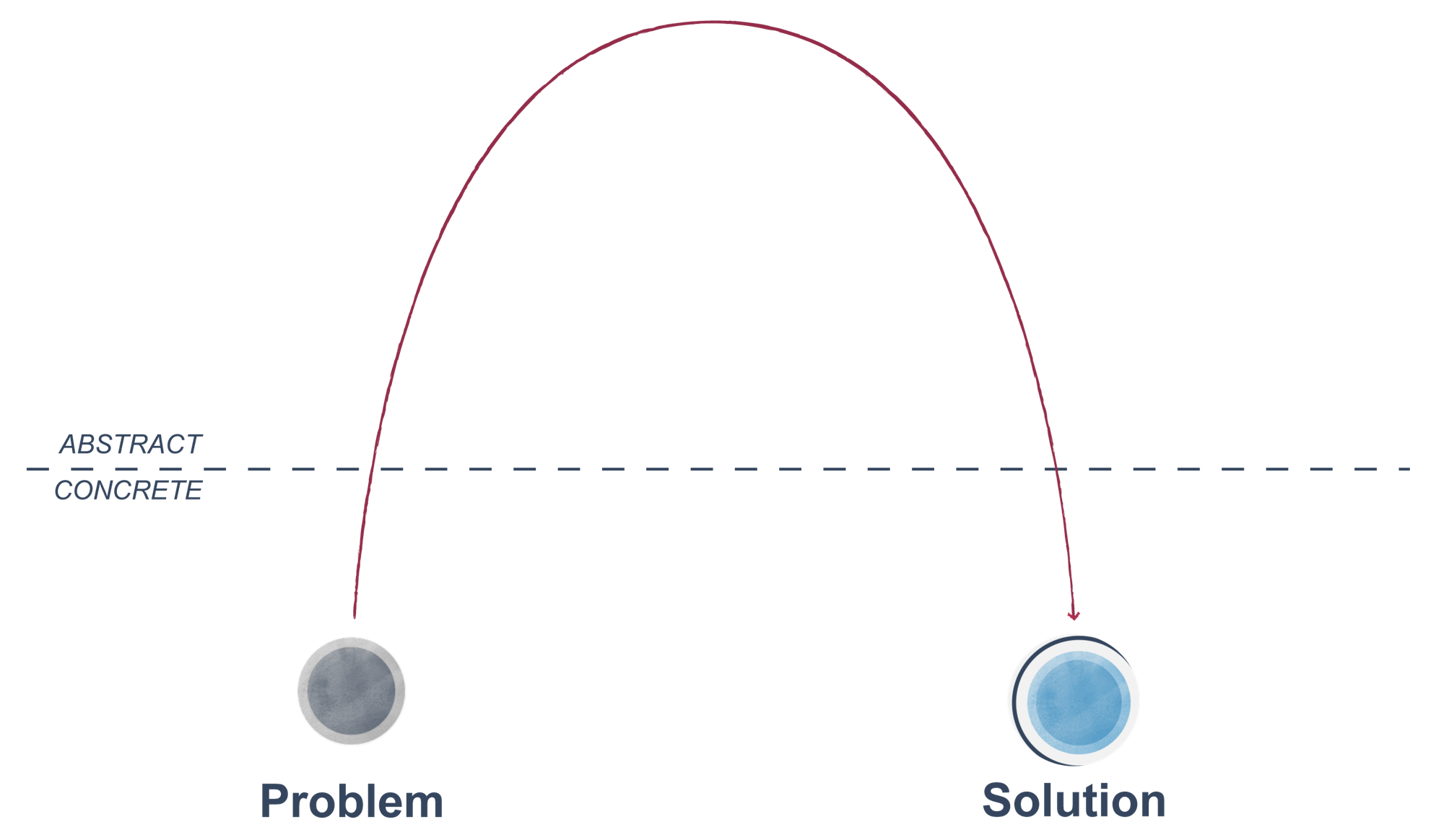

The structured innovation approach straddles two different types of thinking - concrete and abstract. The four phases - clarify, ideate, develop, and implement move from concrete to abstract, and then back again.

- Clarify phase focuses on the clarification process.

- We start by using various tools and frameworks to make concrete observations about users.

- Then we move from the concrete to the abstract to reevaluate the context of the problem by reframing it and approaching it from different perspectives to gain insight on the design question.

- Finally, we start looking for areas of opportunity, and thinking about what we might do with our research information.

- Ideate phase - we move to ideation. Here, we use methods like Systematic Inventive Thinking (SIT) and other tools to overcome cognitive fixedness and come up with new and innovative ideas that may resolve the problems we identified earlier.

- Develop phase - we begin to bring abstract ideas into the concrete world. This phase involves developing concepts by critiquing a range of possible solutions, and using prototyping, testing, and experimenting to answer the critical questions about the concept's viability.

- Implement phase - we test effective communication to stakeholders and reflect on innovation management strategies.

To understand why the innovation process takes a curved path going from the concrete to the abstract, and then back to the concrete, recall that a successful innovation must be both novel and useful. Venturing into the abstract space increases the prospect of the innovation being novel. But for it to be useful, these abstract ideas must be made concrete to solve customer pain points.

It's important to remember that while these four phases are part of a process, it's not often a linear process of one phase following the next. For example, as you prototype concepts in phase three, you may discover results that force you to return to phases one and two to reframe your question. Do not think of this as a setback. Iterating on solutions is a normal and expected result of design thinking.

The concept of design thinking has occasionally been oversold as a one-size-fits-all technique that any team can use to generate great ideas. In reality, the design-thinking approach provides structure but does not demand rigid adherence to one specific process. How you apply the phases, and the tools and frameworks within them, is up to you.