Developing Research-Based Personas

Ideate - User Values and Behaviors - Designing for Behavior Change

Learning Objectives:

- Identify the characteristics of a useful user persona

- Apply knowledge of personas to real design problems

In health care, education, technology, and many other fields, how do you proceed when innovation requires you to inspire and maintain behavior change? How do you get new behaviors to stick? We know from our own daily experiences that people have an instinctual resistance to change. Think about the challenge of following New Year’s resolutions or switching to a new software program at work. And if you’re a manager, you’ve likely seen how upset people can get when even small changes are announced.

Encouraging behavior change is difficult, so it deserves special attention as an outcome of innovation. The tools in this and upcoming articles will help you put users in a better position to change the way they interact with a new product, service, business model, or strategy.

Let me quickly summarize the tools that we will analyze in the context of the Insigne Health case. First, we will explore personas, which are fictional composites based on research on your target users. Contrary to how personas are sometimes presented, you do not need assumptions about demographics to create them. In fact, relying on demographic information can be counterproductive in design discussions. Creating personas without common demographics can be beneficial because the process is guided by research.

Next, we will use personas to experiment with a specific behavior change tool, the BJ Fogg Behavior Model. The Fogg model will help you analyze the motivation and ability of your target users. The goal is to create a cycle that, if successful, will reinforce positive behaviors and help users motivate themselves to act.

With that in mind, let’s move forward with the case. Remember that Insigne Health wanted its members to think of health insurance as a solution for well-being, not just illness.

Segment A

Think again about healthcare providers’ original framing of the problem at hand:

- “Why aren’t patients doing more to protect their health?”

We explored one possible reframing earlier:

- “How might we make patients excited about changing the habits they can change?”

But Insigne Health and Elizabeth Quinby modified this framing in a significant way:

- “How might we make the Silent Middle excited about improving their health and well-being?”

The expression well-being provides a more comprehensive goal than health alone. It suggests that healthcare can be about more than the absence of illness. Healthcare can include positive characteristics like physical energy and mental tranquility too.

With this new framing, Elizabeth Quinby could gather fresh observations. But there were no demographic patterns in the Silent Middle. People varied by age, race, sex, gender identity, and other demographic categories. Fortunately, you do not need demographic patterns to construct a very valuable tool for evaluating user behavior: user personas.

- A user persona is a fictional composite that presents the goals and behaviors of a particular group of users. When you are constructing a persona, your first focus should be on the goals that some people in the researched population have in common.

The rest of the persona can be filled out with concepts you already know how to develop: the population’s pain points, and the design principles that would make solutions work for them.

In the following video transcript, Christi Zuber shares more on developing effective user personas:

There are a few things about creating personas that you have to be very mindful of. One is that some people tend to lump a lot of characteristics together. If you approach personas this way and combine too much, you’ll end up with a watered-down persona that doesn’t accurately represent anyone.

When designing personas, it’s harder than most people might think. You have to pause and identify the attributes and characteristics that truly matter and bring them to life in a persona. Avoid the temptation to oversimplify to the point where the persona lacks depth and fails to tell you much about the individuals it represents.

One of the strengths of personas is that they provide a quick and effective way to explain and immerse others in who you’re designing for. The more examples, images, and other elements you can include to bring the personas to life—making them pop off the page or screen—the better.

For example, consider a persona of a new mom experiencing her first childbirth. She’s likely anxious, though the specifics of her anxiety may vary. These emotions and her status as a first-time mom create a unique set of needs and experiences. These moms typically have the most questions and might struggle more to adjust if things don’t meet their expectations. Some of these moms might be vocal about what they need, while others might be quieter.

Sometimes, there might be variations within a persona. For instance, a new mom might have a very communal experience, surrounded by family. This communal setting could bring unique dynamics, such as multiple people involved in the process, diverse emotions in the room, and logistical challenges for staff trying to assist effectively.

Understanding these needs, attributes, emotions like joy or fear, and overall experiences is critical. When you tap into emotional drivers, you’re acknowledging that we’re emotional beings at our core. However, it’s easy to slip into the trap of categorizing people by demographics, such as age, race, gender, or other census-like data. These are not often the elements that should drive personas. Instead, focus on the deeper, emotionally resonant factors that truly define the experiences and needs of the people you’re designing for.

For the Insigne Health case, identifying accurate user personas for the Silent Middle would be crucial to improving user engagement. To do so, Elizabeth Quinby conducted in-depth video interviews and used generative research methods such as journaling and visualization exercises to learn more about the Silent Middle member population. She asked open-ended questions such as “What does well-being mean to you?” and “What motivates you to engage in healthy behaviors? What prevents you from doing them more often?”

During the research process, Elizabeth Quinby noticed that similar comments came up often enough to identify distinct segments of the member population: Segment A and Segment B. The following are some of the responses she identified as Segment A:

- “My kids are at the center of my well-being. They influence me, and I influence them too. Money is a big source of tension in our family because it stresses my relationship with my partner. The kids can feel that stress.”

- “Not being sick is a good place to start. And that goes for me, my kids, and my partner. When any one of us is under the weather, stress levels go up. I’m probably not going to the gym in that case.”

- “The kids love soccer and so do I, but my playing days are over. Physically, I could probably do it, but the last thing I need is a sprained ankle or a torn ACL.”

- “I walk around the neighborhood, but it’s hard not to think: Is that actually helping me at all? I mean, I rowed in college. Walking for exercise feels like it just can’t be enough. I used to go to the gym three or four times a week, but that’s not possible anymore. Work and family come first.”

- “We keep to a tight schedule and budget. It’s hard for me to justify a lot of the activities I used to do to stay in shape. Convenience is expensive!”

- “I’m never sure if the ‘healthy’ food I’m eating is actually good for me, or just costs more. And if I’m preparing for a big presentation at work, I’ll probably just eat whatever is nearby.”

It was clear that while Segment A had engaged in physically healthy habits earlier in life, they were unable to engage now because of obligations, particularly family and work. Some had severe financial and time-related constraints. Age and the potential for injury were also making them wary.

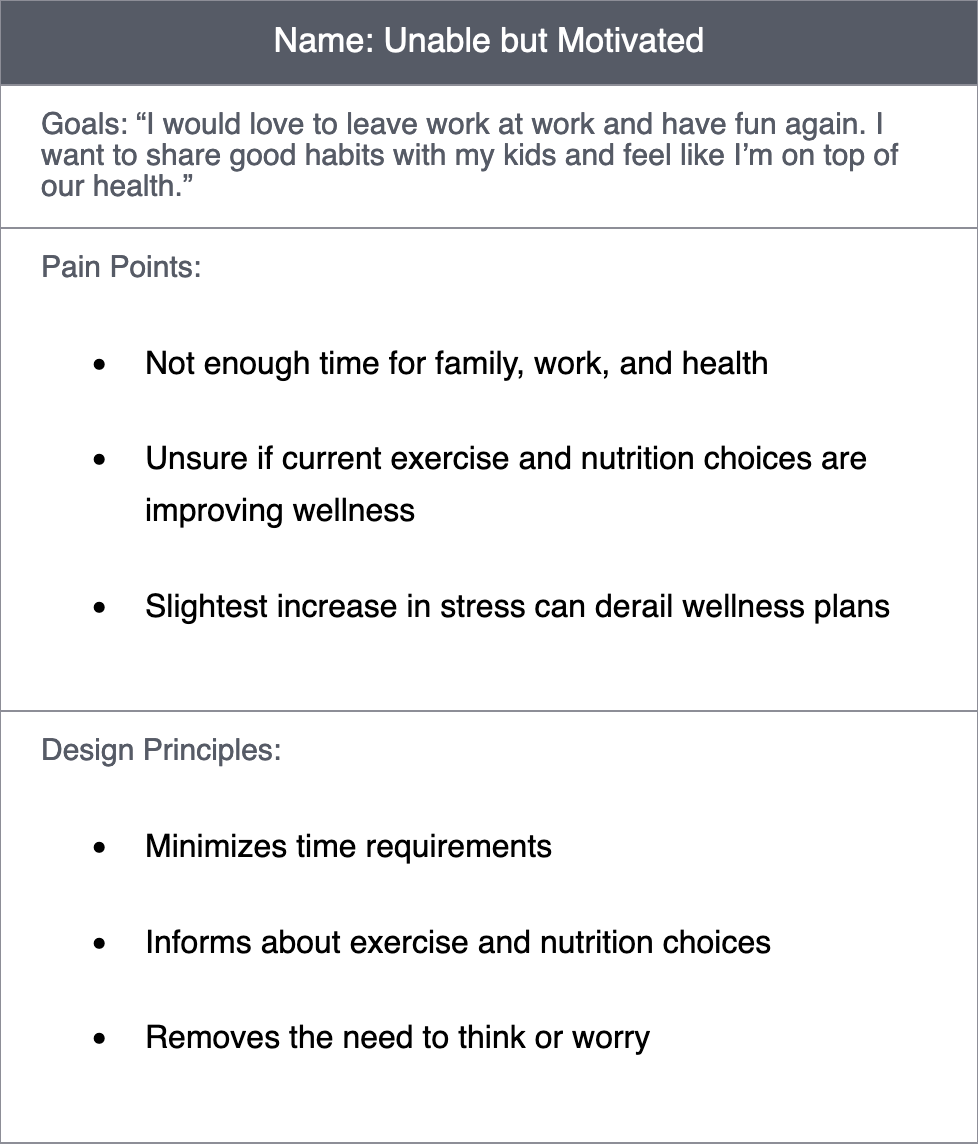

With this information, Elizabeth Quinby had the three things needed to construct a useful persona for Segment A: member goals, their pain points, and some design principles for a solution.

- Goals:

- I would love to destress from work and spend free time with family.

- I want to share good habits with my kids, especially the importance of exercise, eating better, and balancing work and life.

- I’m usually happiest when making good choices.

- Pain Points:

- Not enough time for family, work, and health

- Unsure if current exercise and nutrition choices are improving wellness

- Slightest increase in stress can derail wellness plans

- Possible Design Principles:

- Minimizes time requirements

- Informs about exercise and nutrition choices

- Removes the need to think or worry

Remember, design principles should focus on attributes a solution needs to have, rather than specific solution details, in order to avoid limiting possibilities. Design principles also depend on the problem framing.

In Insigne’s case, the app was not successful in addressing the needs of the Silent Middle—they didn’t use it. So Insigne needed to ideate more broadly, including ideas beyond the app itself.

At this point, Elizabeth Quinby constructed a user persona for Segment A from her research:

The name of the persona summarizes the shared behaviors of the group. The goals statement offers a simple comment from the users’ perspective that encapsulates their group’s shared goals. The user pain points associated with reaching those goals are also included, as are the basic design principles of a solution that addresses those pain points.

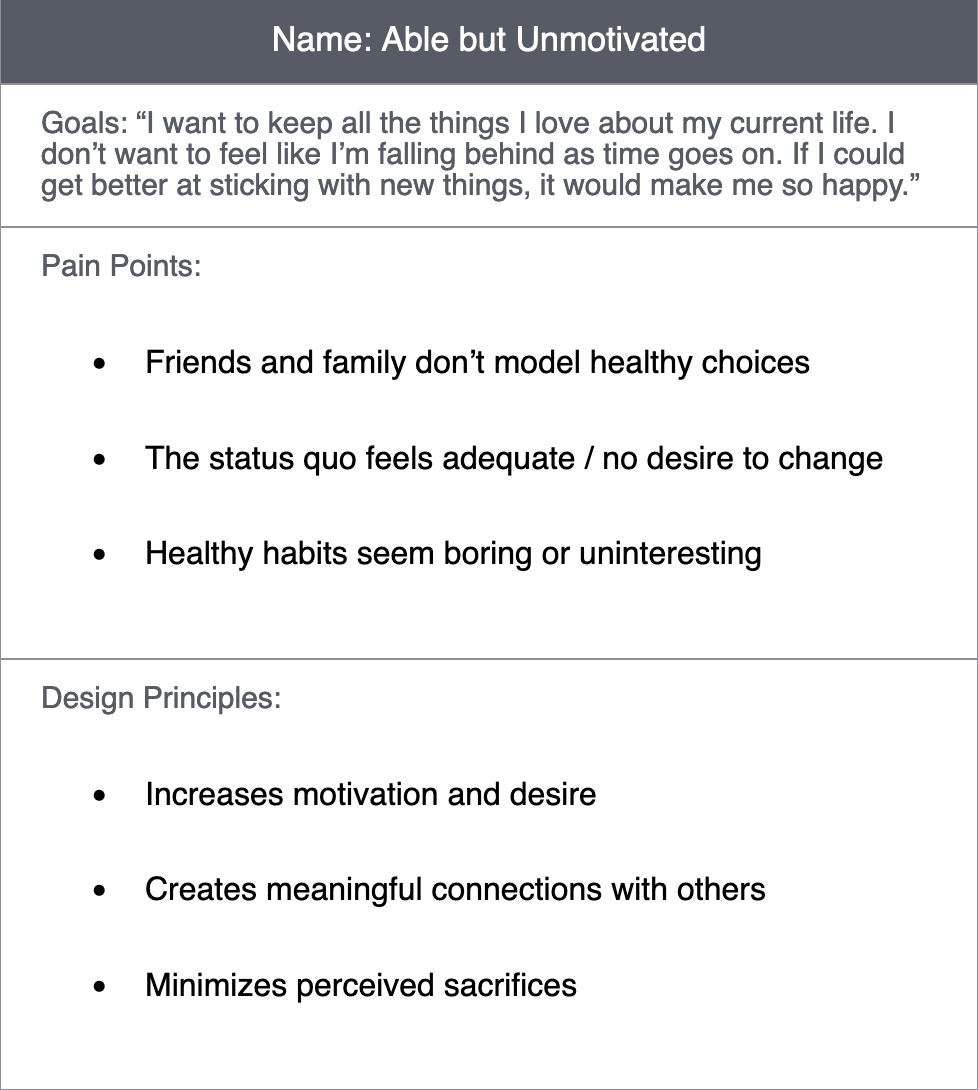

Segment B

The second pattern in the responses Elizabeth Quinby identified, Segment B, is exemplified by the following responses.

- “I think I am okay in health for my age. I want to stay where I am. That may not sound so ambitious, but when the natural trajectory is decline, it’s a reasonable goal. I don’t want to become a burden.”

- “It can be hard for me to stick to something. Challenges come up, and it gets easier to stop than to keep going. I definitely make excuses for myself. I wish I could change.”

- “My partner loves beer. Ten years ago, that was not an issue. But now when we visit our grandkids, they bring us to the local breweries. This doesn’t seem like such a big deal, but I’m uncomfortable that our socializing revolves around alcohol.”

- “I have a habit, I admit, of putting things off. Especially when something really interesting comes along, and that alternative doesn’t require sweat.”

The general persona descriptor for Segment A is “Unable but Motivated,” but Segment B is different in key ways: These members have more time, but they don’t feel the same urge to change. They don’t have the same history with healthy habits as Segment A. They see healthy behaviors as appealing, but they have little motivation. One possible name for Segment B is “Able but Unmotivated.”

If you were doing research for Insigne Health, you would now have two powerful personas to use in innovation discussions. They are based on research and free from subjective assumptions and demographic information. Most importantly, they are simple and easy to apply. Asking, “How would Unable But Motivated react to this app feature?” would result in a focused discussion of goals, pain points, and design principles.

I want to emphasize that this is one of many ways to approach personas. There are other excellent approaches, and some people use them for an additional purpose—storytelling. Later in the design thinking process, for example, you may be communicating the value of a new innovation to internal stakeholders. In that case, applying subjective details and demographic information can make for a more compelling presentation. Those who aren’t familiar with your innovation or the process of developing it might respond more strongly to the journey of Donna instead of Unable But Motivated.

The goal of building personas is to help with ideation by keeping discussions focused on the results of your research in the clarify phase.

Developing personas can be a useful tool for understanding the motivation and ability of your users, but it is not always an easy tool to use. It can be challenging to get personas right. In the following video transcript, Christi Zuber shares more on developing the right personas for your users:

I think some other common mistakes with personas is trying to make them too professional, if I could say it in that way.

You know, I think with personas, the purpose of a persona is to get you to connect and feel for someone who might be different from you. And so I think in corporate America, we’re often accustomed to putting things together that has a kind of mechanical feel to it. It has a certain look and feel. It’s more business language.

And I would say in personas, personas is–it’s the embodiment of a group of people that are living, human beings. Don’t be shy about bringing emotions into it.

I would probably say that about every step, honestly, of the design thinking process, is, design thinking is a beautiful way of acknowledging that we’re human beings. We’re living, breathing human beings, and we’re not logical creatures, we’re emotional creatures.

And so when you create a persona, bring some of that. Breathe life into it so that you can better connect with people as people when you’re looking at it, not just as objects that you’re trying to change or sell to or what have you.

They’re living, breathing human beings, and so try to let the persona begin to bring that to life for you and your teams.

In addition to personas, another way to create lifelike and valuable profiles from your observations is to use point of view statements.

- POV (Point of View) Statement: A statement of the problem you are trying to solve, for whom you are trying to solve it—this could be many people—and why.

To start, use the POV template created by the Interaction Design Foundation: “[User] needs a way to [verb] because [insight].” For example, we could generate one of many POV statements from the research into mopping that we studied earlier:

- “[Aging man] needs a way to [reliably and safely clean (e.g., reach high and hidden spaces)] because [he takes pride in his home and enjoys entertaining.]”

- As we explored in Clarify phase, an insight is the revelation of a new perspective. In this case, we may not have assumed, before research, that entertaining and taking pride in cleanliness were important to the target users. Realizing this insight through research would guide the creation of design principles, personas, and POV statements.

Like a persona, a POV statement helps you evaluate how user focused your ideas are, and judge whether you are truly creating value for the target audience.

One possible POV statement for someone from Segment B in the Insigne Health case is the following: Middle-aged parent needs a way to feel interested in or excited about healthy habits because they’re worried health might affect their lifestyle soon if they don’t make a change.