Early Experiments: Paper Prototyping

Develop: An Experimentation Mindset - Prototyping: From Exploration to Validation

Learning Outcomes:

- Apply your understanding of critical questions to design quick paper experiments

- Evaluate a paper prototype using previously introduced tools

Exploring critical questions is the heart of prototyping. But the develop phase of design thinking also has a clear end, an innovation concept ready for implementation. Unlike the ideate phase, which encourages divergent thinking, your explorations here must evolve and reach a conclusion.

It was designer Bill Moggridge who said, “Fail early, fail often, succeed sooner.” But failure without development is unproductive. Each iteration must be followed by compromise and decision-making. It is a process that moves from exploration to evolution to validation.

As you progress, the number of ideas being tested in your concept should decrease. In exploration, you will focus on low-quality prototypes to discover, as quickly as possible, which assumptions are correct and which are incorrect. This is how the design of your innovation takes shape.

As you make decisions, prototypes will make the design of your innovation more refined, and the quality of your prototypes will improve. In the Two Ovens example earlier, the foam board prototype of the restaurant in the warehouse would evolve into experiments with a real oven and real food.

Finally, as you approach validation, the number of ideas being tested decreases again. You are now working with prototypes that are close to the quality of the final innovation. To return to Two Ovens, these would be tests in a pilot location.

We will explore the increasing complexity of prototypes further, including how you can manage the process of development that leads to validation.

One of the simplest forms of prototyping is paper prototyping, which involves creating a paper replica of an interaction or digital interface. This might mean using multiple pieces of paper and moving them around to replicate interactivity.

Paper prototypes are an excellent example of Tom Chi’s three principles of rapid prototyping (find the quickest path to the experience, doing is the best kind of thinking, and use materials that allow you to move at the speed of thought) because the result only has to look like the real thing—it doesn’t need full functionality. Even with limited time and resources, it is relatively simple to create a paper prototype and see how a user might interact with it.

In the following video transcript, Christi Zuber of Aspen Labs explains how a paper prototype developed into a digital experience in a maternity ward.

So, some examples of prototyping–I’ll give some examples of paper prototypes. And then I’ll give some examples of interactions and technology because there’s– just to have some things to anchor to.

One example of doing something as a paper prototype is when we were working with new moms around this journey from the time they found out they’re pregnant until six weeks after they had children. One of the things we were trying to change is how the communication was beginning to happen when they were in labor and delivery.

Lots of activities are occurring. People are coming in and out of your room all the time. It’s actually quite confusing for the mom that’s there, particularly if it’s their first child. And so we were trying to come up with, what are ways that we can make this more transparent for the mom so that they have a better understanding about what’s happening, how’s it going, and what to expect?

It was a lot of these expectations because when you don’t know what’s happening, you don’t know why someone’s in your room, you don’t know what’s coming next, that’s not a good feeling. And you don’t feel very empowered at that moment. You’re a new mom with a new child. And the last thing you need is something else that makes you feel like you don’t know what you’re doing.

After a baby is born, mothers and hospital staff perform a number of tasks. For example:

- Bonding and breastfeeding

- Meeting with a lactation consultant

- Cleaning, weighing, and examining the baby

- Vaccinations

- Paperwork (birth certificate, etc.)

CHRISTI ZUBER: And so we played around with lots of different things. We did a deep dive and came up with lots of ideas and literally sketched some things out on a big piece of poster board and made–it was like a calendar, I guess, of sorts, like a giant calendar that would list off, here’s all the things that need to be done.

And we went into the mom’s room with our poster, and we would say, “OK, if you had something like this, what questions would you have or what would you do?” And so we got feedback of, well, I don’t know. You know, if something didn’t happen at that time, I’d be a little concerned. You know, maybe am I behind schedule? What does that mean? I like seeing what the items are, knowing what happens.

So we took that feedback and said, OK, they like knowing what happens. Whew, hadn’t thought of maybe the times. That might be a little bit of overkill because I don’t know if we can control all the times things need to happen, but it sounds like knowing something is going to happen and that it’s been done is really important.

So then we went back. We evolved this poster board. We then went back out, got some feedback. Seemed like we were on the right track, so then we laminated them in an office-type setting. So we laminated them, brought them back into Labor and Delivery. We Velcroed them up on the wall. So it was a laminated poster board. We took a string, and we attached like a whiteboard marker to it. And we had these cards that we made, and each card was a representation of what the different activities were.

And then we had one column that said To Do and all these cards Velcroed there, and then we had another column that said Completed. And so the idea was, all these cards start off in one column– and it was Hearing, Hearing Screening, Birth Certificates, all these different things that needed to happen. And so, as they would happen, then we asked the clinicians coming into the room to just move the card over to the other column when they left.

So we did that, got feedback on it, and the moms said, that’s great. I can now see how many things that there are to do, how many things we’ve accomplished so far. I can tell, actually, I’m probably getting closer to being able to kind of move on. And so that was great. They had a sense of their timing and sequencing. But they said, you know, I have some questions about this screening thing, this hearing screening. What is that?

So then we mocked up kind of a brochure of sorts or something that they could keep at their bedside that had some of the details in it if they were interested. We put that into, eventually– it started off in three patient rooms, then we put it across an entire unit at a hospital. Then we did it into three units. And then we evolved that to the point where then we actually created–it was called the Journey Home board, and we produced them and put them into, at that point in time, I think it was 37 hospitals.

And those have now evolved into digital boards. So, within about the last five years, those evolved, now, into digital boards, and it’s the same kind of tracking, the same basic mechanism.

As this example demonstrates, rapid prototyping may begin with a paper sketch and evolve into a gradually more elaborate design. The experimentation mindset can improve even a small innovation—like a new way to inform users moving through an experience.

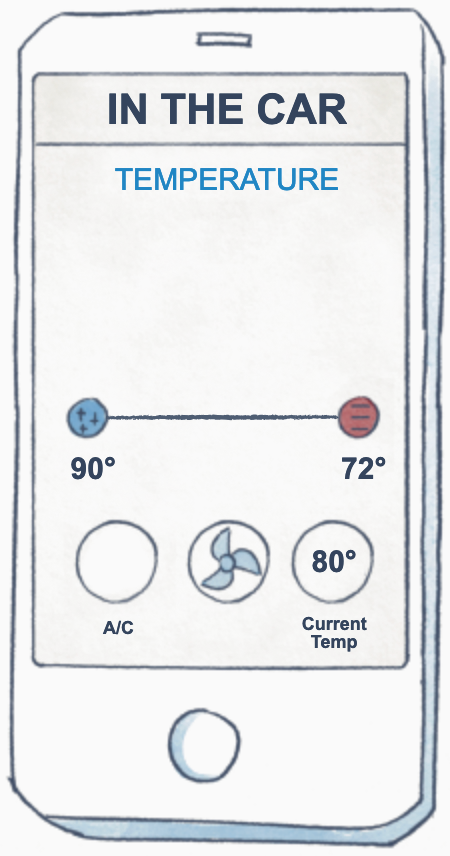

Imagine that you are designing a phone app for car owners that will allow them to perform functions like turning the car on, adjusting the heat, and so on. You are creating simple paper prototypes of these functions.

Let’s examine one specific prototype of the temperature modification screen. Instead of the evaluation tools, you can also use the design heuristics to interrogate the design.

Which changes would bring this design more in line with the “match mental models” heuristic?

- Changing the colors and/or patterns of the temperature dots

- In many temperature-related interfaces, red is associated with heat, and blue with cold. Switching to this color scheme is likely to make the controls more intuitive for users. Similarly, the snowflake-like pattern would be better associated with colder temperatures.

- Putting lower temperatures on the left

- In the US, people tend to think of numbers as increasing from left to right. Putting lower temperatures on the left would meet this expectation.

- Removing the fan icon

- A fan icon is common on traditional car dashboards. Displaying this option clearly will match users’ existing mental models.

- Raising higher temperatures above lower ones

- In the US, people tend to think of numbers as increasing from bottom to top. Raising higher temperatures above lower ones would meet this expectation.

So, options 1, 2, and 4 are correct.

Let’s examine one possible iteration on the temperature gauge design.

In this revised design, the colors now match users’ traditional mental models for temperature, with blue for cold and red for hot. And the vertical placement of the colors also anticipates users’ expectations, with warmer temperatures higher than colder ones.

This is where your prototype can evolve. What other critical questions can this experiment answer?

This is another time when feedback is critical. Paper prototypes are ideal for early experimentation because they’re often the quickest path to the experience. But importantly, they also make it easy to invite feedback from a variety of stakeholders.

Programmers, marketing, sales, and people in other positions would all have unique and valuable feedback. For example, you could learn if this design is possible to program, whether your ideas are compatible with branding, how the design looks compared to competitors’ offerings, how the design fits with what customers are demanding, and so forth.

Make sure that you invite feedback from diverse perspectives, especially when you’re working on early experiments like paper prototypes. This increases the likelihood that the final design of your innovation will match the needs of multiple stakeholders.