Establishing Focus with Design Principles

Ideate - Tools and Frameworks for Generating Ideas

In the upcoming articles, we will explore the ideate phase of design thinking in depth.

From Research to Design Goals

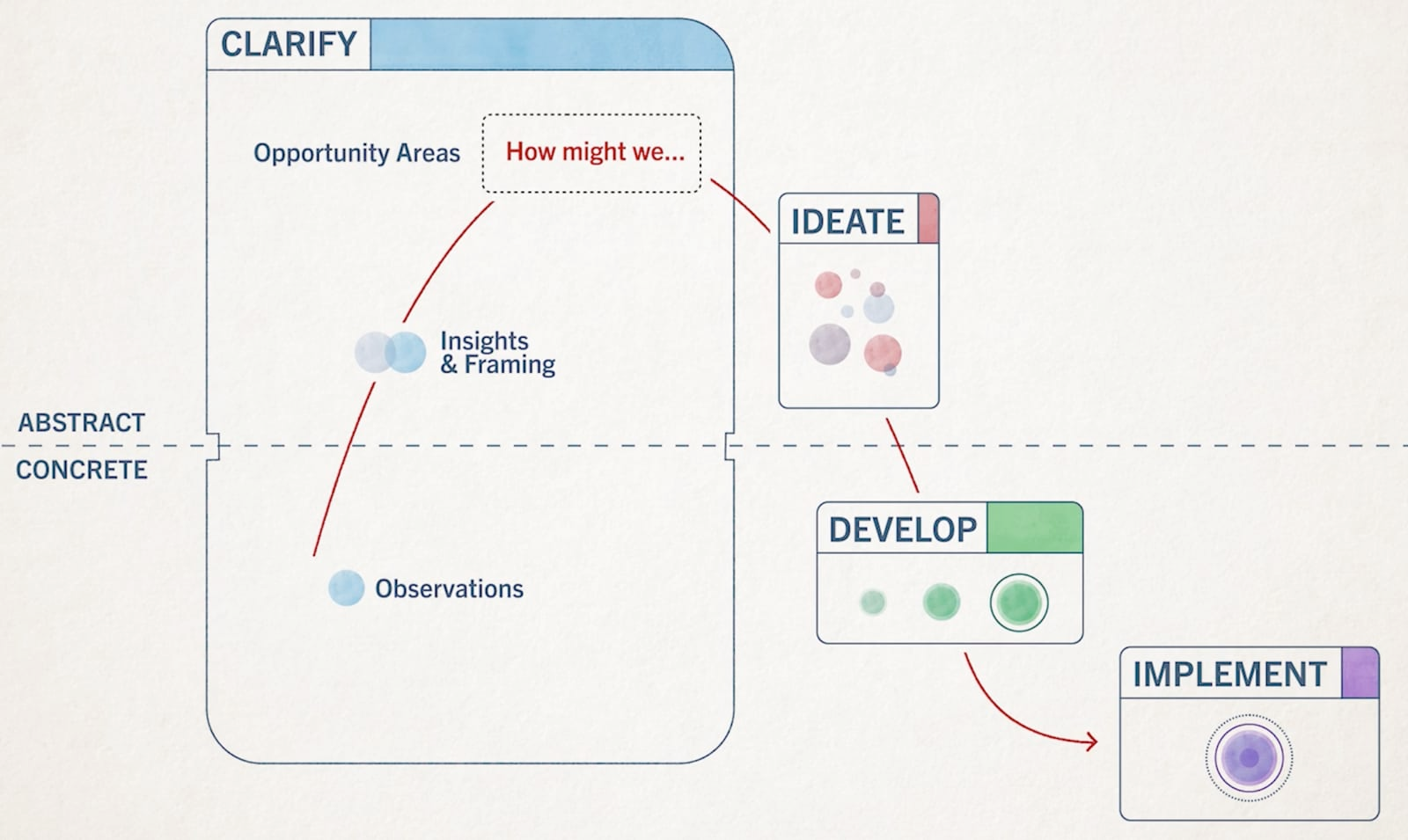

The first phase of the design thinking process was clarify. In that phase, we explored the importance of making concrete observations to identify pain points. We then moved into the abstract, using research insights to frame the most interesting design problem and identify areas for opportunity.

Now that you have laid this groundwork, you can engage with the second phase of design thinking, ideate. In the ideate phase, you will need to think creatively as you manipulate the various attributes and characteristics of a product or situation. This is difficult mental work, but we will provide numerous tools to help you rethink assumptions, come up with ideas, and evaluate them against user needs you have identified.

To complete this work effectively, you will need to become more aware of how you think and how this might interfere with the creative process. You will learn how to overcome common mental blocks called cognitive fixedness. Once you know how to move beyond these blocks, you will be free to ideate and brainstorm with confidence.

But before we begin, we have to start by defining how user research translates into guidelines for ideation. In other words, by defining our design principles.

In Clarify articles, we explored some of the pain points associated with mopping. Some examples are:

- Mopping is physically taxing.

- The mop can’t reach some areas easily.

- Users may need to stand on a chair to reach difficult places, increasing the risk of a fall or serious injury.

- The mop itself is difficult to clean - and takes a lot of time to clean.

- Cleaning takes time and leaves water on the floor to dry.

- The mop is too long or too short for some users.

- The user needs to be near a water source to empty and refill the bucket.

- The user is often unsatisfied with the level of cleanliness: this may result in lack of pride, embarrassment, and reluctance to socialize.

If you had to place these pain points in two or three categories, how might you name those categories? Think of broad commonalities in the types of problems they present.

I asked you to categorize a series of pain points because I wanted you to think about something very simple. What do these pain points have in common? This sort of comparison leads naturally into the next topic, design principles.

Design principles are the attributes that ideas must have to respond effectively to the identified pain points. The work you completed in the clarify phase established the foundation for the design principles that you will ideate toward.

It's important to make the distinction that design principles are not solutions. When you are thinking of the attributes of a possible solution, try not to anticipate what that solution might be. Simply look for commonalities in how the pain points could be addressed. The more general these characteristics are, the broader your solutions can be.

To illustrate what I mean, let's think back to the pain points related to mopping. For example, mopping is physically taxing, and it is difficult to reach certain areas in the house. Also, the mop was too long or too short for some users. What do these pain points all have in common? They indicate issues with ease of use and convenience.

What else is a problem? The mop gets dirty as you use it, and then you have to change the water. Otherwise, you're just spreading the dirt around. In fact, that dirty water might be left on the floor to dry, which is counterintuitive for a cleaning product. So another characteristic of our solution should be cleanliness.

Finally, there is the time it takes to mop. You take the mop out, fill the bucket, add the cleanser, mop the floor, empty the bucket, clean the mop, start over. As you observed, mopping a floor in the traditional way takes time. Another design principle is reduced time to clean.

It is helpful to think about design principles as the overlapping circles in a Venn diagram. Solutions that overlap with more design principles are more likely to have high desirability. In essence, this encourages us to aim for solutions that align with as many design principles as possible to create highly desirable and effective outcomes.

Design principles are the attributes that a potential solution must have to effectively address the pain points identified in your design research. They allow you to do the following:

- Establish goals for ideation

- Design principles help you keep team discussions focused on user needs.

- Comprehensively evaluate your ideas

- With clear design principles, you can evaluate how desirable an idea might be, and how it compares to other ideas.

- Identify and evaluate tradeoffs

- Some design principles may be impossible to fully implement together, and designers must often choose between two competing goals. Strong design principles help you decide what to prioritize.

Tradeoffs are especially important to consider at the beginning of the ideation process. Consider, for example, two critical design principles that often appear in IT security innovations: security and ease of use. They are in direct tension with each other - as in multifactor authentication, which makes systems more secure but inevitably makes the login process more difficult.

You cannot fully resolve that tension, but you can make an early decision about where on the spectrum you want your solution to fall.

What are some tradeoffs that you might have to consider in the three design principles for a floor-cleaning product: ease of use, cleanliness, and reduced time to clean?

The design principles “ease of use” and “reduced time to clean” may require compromises in the level of “cleanliness” that a potential solution can achieve. This is where you can refine ideas by considering strategic goals as well: Are you targeting the market for professional cleaning products, or are you competing for casual home users? These considerations will help you make ideas even more user focused.

Now that we have established the benefits of design principles, let’s focus on how to create them.

Observing people using a mop allowed us to express what might make the process easier: not scrubbing as much, not having to clean the mop, being more efficient with water, and so on.

- The goal when creating useful design principles is to translate concrete observations into more general, abstract phrases, like “easy to use.”

More generalized design principles expand the possibilities for a solution. For example, a design principle like “easy to lift” assumes that you need to lift something. “Easy to use” is a broader way of expressing the same idea, but it allows more freedom for exploration, such as using a robot to clean.

In addition to the explicit pain points for the mopping example, recall these latent pain points that we identified in the previous module:

- Users dread the task of mopping because there is so much repetition and perceived wasted effort.

- Users want to take pride in keeping their houses clean, but the effort required makes them put it off. This can lead to shame and other negative feelings.

- Worries about injury place a psychological burden on users, especially the elderly and their caretakers.

After considering these needs, we have selected three design principles: cleanliness, reduced time to clean, and ease of use / convenience.

Do you believe “low cost / low price” should be an additional design principle for an innovation on the traditional mop?

The value added from responding to the latent pain points - particularly lowering the sense of wasted effort, and reducing the worries about injury - would be large enough to allow for more value capture in the form of a higher price.

The choice to focus on price and cost will depend on context. In this case, of a cleaning product, the higher price is unlikely to be a significant burden for many users.

Reviewing user research to develop and refine design principles is important for establishing focus for ideation.

Design Principles in Use - The Creative Matrix

Systematic Inventive Thinking (SIT) is a structured methodology for innovation that focuses on using existing resources and constraints to generate creative solutions. Unlike traditional approaches that seek inspiration from external ideas, SIT works within the “closed world” of the problem, encouraging out-of-the-box thinking by leveraging what is already available.

Earlier, we explored design principles as overlapping circles in a Venn diagram. Moving forward, you will see them in the creative matrix, a table that provides structure for ideation.

The creative matrix was introduced in a slightly different form by the LUMA Institute, among others, to help organize the ideation process. The creative matrix encourages you to ideate systematically and broadly. You note the design principles in the column headings at the top of the matrix. There, they provide criteria for comparing your ideas to your research. Each row contains a tool you can use to generate ideas. Ideas are compared to the design principles and entered into the matrix.

The Creative Matrix is a brainstorming tool that helps generate innovative ideas by organizing potential solutions into a grid format. One axis of the matrix represents categories like user needs, features, or challenges, while the other represents influences like technologies, markets, or trends. By filling the grid, teams explore unique combinations, encouraging out-of-the-box thinking and structured creativity for problem-solving or product development.

For example, let's return to the mop problem. The core design principles we will keep in mind are cleanliness, reduced time to clean, and ease of use or convenience. With these principles at the top, you could then apply the SIT thinking tools or other approaches, like brainstorming. You simply plug ideas into the cells beneath the design principles they fulfill. If this seems like a lot to comprehend, don't worry. We will introduce each tool in upcoming articles individually, and as we proceed, you will gradually understand how to use the creative matrix and how useful it can be.

Since the mid-1990s, the design consultancy Systematic Inventive Thinking (SIT) has helped organizations develop innovative solutions to everyday business problems using their thinking tools and principles, which provide a structured approach to ideation.

The function of the tools is to inspire creative thought. The function of the design principles is to serve as a guide or reminder of your end goal.

In the upcoming articles, you will learn how to ideate using the creative matrix. You will quickly apply one of several thinking tools to generate ideas without worrying about feasibility, viability, and other concerns.

If an idea does not immediately fit at least one design principle, it is important that you do not simply dismiss it: place it to the side instead. These tools will be applied and reapplied throughout the creative process to re-evaluate, refine, and develop ideas.

The creative matrix provides a framework for assessing how well ideas might fulfill user needs. It does so by evaluating these ideas against your design principles.

How do you think problem framing affects the creation of design principles and the evaluation of different ideas in the matrix?

Different problem framings result in different design principles and different ideas. In design thinking, it is important to reflect on both the pain points and the problem framing before you create design principles and enter them into a creative matrix.

It is always useful to double-check your design principles against the problem framing before ideating. For example:

- “How might we make cleaning fun and easy?”

- The current design principles - effectiveness of cleaning, reduced time to clean, and ease of use and convenience - would match this framing well.

- “How might we make cleaning fun, easy, and environmentally friendly?”

- If environmental sustainability was crucial to the brand and target consumers, you might create different design principles to ensure environmental sustainability, and then evaluate ideas differently.

This is why it is so important to know the problem that you are trying to solve, and to frame it correctly at the outset.

Design thinking is a flexible framework, and you can take whatever you need from it to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of innovation. However, it is valuable in the beginning to learn the whole structured process - including research, problem framing, design principles, and the other tools and frameworks you will learn here.