Evaluating Ideas

Opportunities are Everywhere

Let's dig into the economics of a venture. There are many potential opportunities in the world, but how can you determine if an idea is good? We’ll introduce some tools for evaluating ventures. We’ll estimate how much customers are willing to pay, the total size of the market, the level of operating and capital costs, and the cost of capital. A great opportunity is one in which the discounted present value of cash inflows is much higher than the present value of outflows.

Evaluating An Idea’s Value

Let’s start with a hypothetical venture - let’s call it Motion Alert. Suppose the owner John has a new idea for a battery-operated, wireless home safety device that detects motion in rooms and notifies the owner. John estimates that he will have to spend $1 million to perfect his design, apply for patent protection, arrange for another firm to manufacture and ship the device, and contract an independent sales organization. He has no employees on his payroll, and he owns 100% of the company.

Based on research and interviews, he thinks the product will retail for $15, a price that is significantly lower than the competition. John can buy the devices from the manufacturer for $6.00. The sales organization wants $2.00 for each unit sold, and the retailer needs $3.00. That leaves John with a pre-tax profit of $4.00 per unit. He has a personal tax rate of 40%. He prepares a simplified cash flow forecast for his venture, detailed below.

Assumptions:

| Year | 0 | 1-3 |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Investment | ($1,000,000) | |

| Units Sold | 1,000,000 | |

| Retail Unit Price | $15.00 | |

| Retailer Margin | $3.00 | |

| Price to Motion Alert | $12.00 | |

| Manufacturer Price | $6.00 | |

| Selling Unit Cost | $2.00 | |

| Retail Sales | $15,000,000 |

Forecasts:

| Year | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenues | $12,000,000 | $12,000,000 | $12,000,000 | |

| Cost of Goods Sold | $6,000,000 | $6,000,000 | $6,000,000 | |

| Gross Margin | $6,000,000 | $6,000,000 | $6,000,000 | |

| Selling Expense | $2,000,000 | $2,000,000 | $2,000,000 | |

| Operating Profit | $4,000,000 | $4,000,000 | $4,000,000 | |

| Taxes @ 40% | $1,600,000 | $1,600,000 | $1,600,000 | |

| Net Income | $2,400,000 | $2,400,000 | $2,400,000 | |

| Net Cash Flows | ($1,000,000) | $2,400,000 | $2,400,000 | $2,400,000 |

Creating a model of a venture’s basic business model and cash flows is critical to understand how to select, build and finance a venture.

As you can see, John has an idea that requires a modest investment ($1 million) and generates attractive cash flows for three years. John assumes that competitors will develop similar products and enter the business, which is why his sales drop to $0 at the end of three years. Competition makes it harder to sustain prices and profit margins.

Cost of Capital and Present Value

Suppose I told you that you could choose between receiving $1.00 today or $1.00 one year from now. Most rational people prefer cash sooner to cash later. You could spend it immediately or invest it and earn some rate of return. Then you would have more in a year and could decide then if you want to spend it or reinvest it.

Similarly, if someone borrows money from you, you want compensation, so you charge them interest. There is a market for money in which savers and borrowers determine how much it costs to borrow and how much the saver gets paid to lend. That cost of money depends on the length of the loan and how risky it is.

If the cost of money for one year is 10%, for example, then I can determine the future value of $1.00 invested today and the present value of $1.00 received one year from now. If I invest $1.00 today, I will have $1.10 at the end of the year ($1.00 * (1 + 10%)). Or, if I will receive $1.00 at the end of a year, the present value is $0.909 ($1.00 / (1 + 10%)). That makes sense because, if I invest $0.909 for one year at a 10% rate, I will end up with $1.00.

Obviously, if I change the time involved, the values change. If I invest $1.00 for 2 years at 10% per year, I end up with $1.21 ((1+10%) * (1+10%) * $1.00). If I get $1.00 in two years, that is only worth $0.826 ($1.00 / ((1+10%) *(1+10%))).

Almost all entrepreneurial ventures involve investing up front in hopes of getting returns at some point in the future. The obvious question is: How do I consider the timing of possible cash flows in a venture? That is why we apply a discount rate to annual free cash flows to reflect the time value of money and the riskiness of any investment.

In the simple example, I have applied a discount rate of 10%. Deciding what discount rate to apply is very complicated. Most investors would want a higher return from a risky entrepreneurial venture.

If we assume that the discount rate (the opportunity cost of capital) is 10%, then the present value of the cash flows is approximately $6 million and the net present value after subtracting the required investment is $5 million. This seems like a very attractive project - if he can pull it off.

There is a gap between the present value of inflows and outflows. John thinks his idea can generate retail revenues of $45 million over three years. John’s venture only collects $36 million of the $45 million, with the retailer getting $9 million. Motion Alert pays $18 million to the manufacturer, $6 million to the independent sales organization, and $4.8 million to the government for taxes, leaving $7.2 million for John. If I adjust these totals by discounting them back to the beginning at 10% per year, which is the cost of capital, I get this:

| 3-Year Total (millions) | Present Value (millions) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Value From Customer | $45.0 | $37.3 |

| Retailer Margin | $9.0 | $7.5 |

| Sales Organization | $6.0 | $5.0 |

| Manufacturer | $18.0 | $14.9 |

| Taxes | $4.8 | $4.0 |

| Motion Alert | $7.2 | $6.0 |

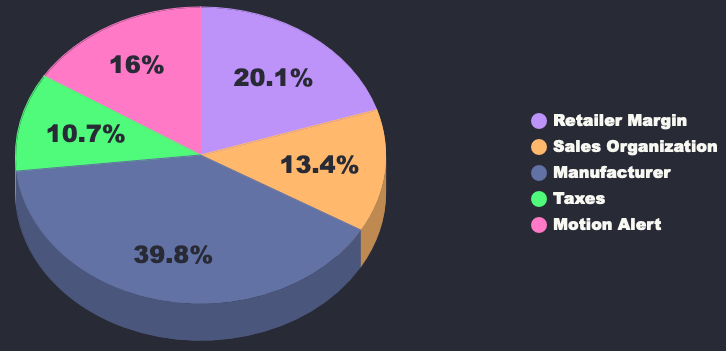

The size of the pie reflects the total amount customers are willing to pay (in present value terms) for John’s product ($15 million for three years, discounted at 10%). The slices represent the cost of acquiring resources from the retailer (for distribution), the manufacturer, the sales organization, and the government (as taxes). The remaining slice belongs to John - that is the value of his idea. He owns 100% of the stock but keeps 16% of the value pie ($6 / $37.3) because he needs external resources.

This example captures important elements of the entrepreneurial process - identifying an opportunity (a product for which customers are willing to pay more than costs), marshaling resources (suppliers, sales reps, retail access, etc.), executing on the idea, and harvesting (converting an investment to cash).

Sizing the Market

One of the most important issues confronting entrepreneurs (and investors) is figuring out the total market size for any proposed venture and the possible share of that market that the venture can capture. In our simple example of Motion Alert, we made some assumptions about how many devices he could sell at a certain price through retail channels. If the total US market were $250 million per year, then John and Motion Alert would be estimating a 6% share. That might be feasible given John’s low costs and proposed low price.

One of the key goals in estimating total market size and the share that might be possible is to make sure that there is a big enough payoff to justify launching a venture. You don’t want to incur lots of risk if the upside is low, or you would have to attain an unrealistic share of the market to justify the investment of human and financial capital.

To see how the market size estimation process works, consider a relatively recent venture called Casper, which introduced a new mattress, shipped directly to customers. Casper intended to bypass the existing retail channels. Customers would order online, Casper would stuff the mattress in a small box (the mattress is made from a viscoelastic, foam material), and it would be delivered to the customer’s doorstep. Prices were well below existing comparable quality mattresses, and Casper offered a 100 day, money-back guarantee.

Here is some information about the US market in 2014:

- US Population: 276 million

- Average mattress price (all types): $1,100

- Median Household Income: $53,657

- Current market shares by mattress type:

- 60% Spring mattresses

- 25% Foam Mattresses

- 11% Airbeds

- Number of mattress manufacturers: 429

- Top three manufacturer market share: 47%

- Distribution channels:

- 47% Specialty Stores

- 38% Furniture Stores

- Average time to buy a new mattress: 8–10 years

- Total annual revenue: $8.7 billion

Assuming that every US household needs at least one mattress, and assuming that each household is at least 2 people = 138 million households. Assuming 25% of those households have foam mattresses = 35 million would be a reasonable market share. Given that most US households have at least one mattress, the initial market share is large. However, based on the further information provided, you can see that only 25% of the market share is foam mattresses. Furthermore, the top three manufacturers share 47% of the market and the remaining 426 share the rest of the market share. It seems to be a quite competitive market. In addition, current distribution channels are predominantly in-person stores. Having said this, there is a large opportunity for market disruption based on this data.

Casper is focused on only a segment of the total market of 35 million mattresses. They are selling a foam mattress in a limited number of sizes to adults who are willing to buy online without testing it in a store. Casper probably can’t expect to capture a high percentage of the total market, particularly if there will be competitors using the same business model. However, it might be possible to get a few percentage points of this huge market, which would represent annual sales of over $200 million. If the costs - manufacturing, customer acquisition, returns, etc. - are reasonably low, they might be able to build a profitable business.

Another attractive aspect of this opportunity is that there are obvious product extensions. If the company is successful with mattresses, it might be able to sell pillows, mattress covers, futons or other types of furniture. There might be a global opportunity to use the same business model. In many businesses, there are other opportunities once a company is in the market and achieves some success.

For every venture, the entrepreneurial team must assess the total market and the share they might reasonably win. They also need to identify possible product and geographic extensions. This is a difficult process, but precision is not the real goal. The idea is to convince yourself and your stakeholders that there is enough market potential to justify launching the venture. Also, most ventures get going and discover opportunities only once they are in the market.

Changing Assumptions

The business model and market assumptions you start with can be changed in useful ways. Let's return to the hypothetical Motion Alert example. Suppose John wants to get a partner to invest half the $1 million of required capital. He must give her a share of his slice of the pie. If the partner gets 50% of the equity in return for putting up $500,000, then she earns $3.6 million over the three years ($3 million in present value). That still leaves John with substantial upside. Or, John could have invested all the capital but hired someone to run the venture, giving that person a share of the pie.

Another assumption to explore relates to the duration of revenues from the idea. What if John and Motion Alert can extend the time there are profitable sales from three years to four years. That adds $2.4 million in total cash flow to the pie. John might be able to extend the life of the project by spending money to enforce his patent to defer entry. That is the basic goal in filing for patent protection - to build a barrier to competition that protects a cash flow stream. But, without vigorous enforcement, a patent is not very valuable.

Or, John could invest in marketing and advertising to build a brand that would increase sales or lengthen the economic life of the project. John might also pay the sales rep firm more, or provide a higher margin to the retailer. Obviously, he would be willing to spend a significant amount each year to continue to benefit from the cash flows generated by the project. He might also be able to introduce additional related products into the marketplace.

He would use the same process outlined with the original product - sizing the market, forecasting and discounting cash flows - to evaluate any new product. Even within stable businesses, there are always new opportunities to be considered.

You can begin to see how the elements of the customer value creation and capture process fit together at all levels in an entrepreneurial venture. Customers vote with their pocketbooks and assign a value of $15 to each device - John assumes there are 1 million customers each year who are willing to pay $15 or higher, given product benefits and alternatives. The retailer is willing to allocate shelf space to John’s product because they can make a decent profit relative to selling another product.

The sales firm has choices too about what products they will try to sell - in their case, John and his company are the customer. If that firm charges too high a fee, then John might look for another firm to represent his product. Or John might decide to hire an internal sales force.

It’s the same story for the manufacturer. That firm has choices about which products to build for different customers. They bid for the right to make John’s new device. They set a price that gives them a profit and agree to payment terms (i.e. when they get paid). John might have several firms compete for the contract and will select the firm with the best combination of price, quality, service and payment terms.

Successful entrepreneurs are problem solvers and organizers - they figure out how to create a venture that delivers value to customers, pays all the resource providers, and leaves something for them.

Value Creation and Capture

In our simple example of John’s motion-detection device venture, we made some assumptions about prices, costs, competition, and total demand. We need to dig a little deeper into each of these factors to understand entrepreneurial opportunity.

In economics, we define willingness to pay as the highest price a customer is willing to pay for a product or service, based on their preferences, circumstances, and the external environment. Typically, the higher the price, the lower is total demand because fewer buyers assign a value equal to or higher than the price.

At the same time, suppliers agree to build and sell a product or deliver a service, depending on the price they receive. The higher the price, the more they are willing to supply, given their costs. Where willingness to supply meets willingness to pay at the margin determines price and quantity in a market.

Building Competitive Advantage

If I have a relatively simple product like milk, it’s easy to describe how the market works. Consumers want milk - some are willing to pay more than others. Dairy producers have costs - if they can sell milk for more than their marginal operating and capital costs, they will participate in the market.

The market price is determined by matching supply and demand. In a commodity market like milk, there are many competitors and limits on how much profit any company can make. If price and profits are high, then existing or new suppliers increase supply, driving down prices and profits. It’s very difficult to create a sustainable wedge between revenues and costs when a company doesn’t have some edge and ways to limit competition.

What if someone could develop a new milk product that costs the same to make as regular milk but tastes much better and is healthier? That product might sell for a higher price, allowing the inventor to earn extra profits. But, if all the other suppliers could quickly imitate the new production process, they would increase supply, eliminating the extra profits.

If the inventor could get strong patent protection, they could stop other suppliers from entering the market. The inventor would earn extra profits, selling at the higher price but producing at the same cost. That extra profit would continue until the patent expires, assuming no other major shifts in technology.

The same result would arise if an inventor could develop a patent-protected method for producing high-quality milk at a lower marginal cost than any other supplier. If that inventor sold milk at the “market” price, they would earn excess profits, at least while they kept other suppliers from copying the new technology. In fact, if they could supply all the market, they would drive all the suppliers out of the market.

The idea here is simple - companies that command a price premium and/or produce at lower cost (or both) can earn extra profits. They will benefit until one or more competitors come to displace them.

John’s home monitoring device project is a situation in which there is a big difference between market price and cost, at least for the first few years. Customers are willing to pay $15 per unit, but the total cost is only $11, before taxes. The project earns a rate of return higher than the assumed cost of capital of 10% per year - the internal rate of return is 234%. That is why John owns a valuable slice of the pie.

If John didn’t have an edge on the competition, then his profit margin would be lower, and he would no longer earn a high rate of return relative to the cost of capital. Competitors would enter the market and drive prices down until they (and John) earned no more than the cost of capital. In the model, if prices fall to the point that John’s company only earns $0.67 pre-tax profits per unit ($0.42 per unit, after-tax), then the present value of cash flows is exactly equal to the required investment of $1 million. At that point, the net present value of the project is $0. John might still launch the project, but he might decide to abandon it and search for other high return, low-risk possibilities.

Network Effects - Winner Take Most

The examples used so far - a new home monitoring device and milk - are relatively simple products. Willingness to pay, costs, market size, and competition are more complex in most markets. For example, there are marketplaces like eBay in which the value of the network to any participant, and their willingness to pay, depends on how many suppliers and buyers there are. At eBay, the company needed many buyers and many sellers to justify charging fees for transactions or services.

Companies like eBay benefit from what are called network effects - the value of the network grows exponentially as you add suppliers and buyers arithmetically. In such markets, there is likely to be one winner or perhaps a few. These kinds of opportunities require that the entrepreneur try to win the race because the second-place competitor can’t do very well.

Uber is another example of a marketplace that depends on attracting many users and drivers. Uber offers certain benefits to users relative to the most obvious competition - taxis and limos. Drivers find they can make enough money as Uber drivers because so many customers have the app and want to use the service. Uber can’t charge customers too much or take too large a transaction fee, or the market will disappear. Uber expanded its range of services - from Uber Pool to Uber SUV - to capture as many customers as possible at different price points.

Compound Products

Another consideration could be if you sell a compound product, like a razor and a blade - you might project how much customers are willing to pay in total for shaving, but then charge different prices for each component. Famously, Gillette made low margins on its razors but high profits on its blades. The same was true of printers and ink cartridges - once a customer bought a printer, they were dependent on the original manufacturer for ink, though this dependence eventually changed as new players introduced substitute supplies at lower prices.

A final consideration relates to when customers pay. To illustrate, if you launch a magazine, or a software service, you might get customers to pay in advance of delivering the service. If you get paid up front, that has a dramatic impact on how much capital you will need and ongoing operating cash flows. No matter what business you are in, there are limits to what customers will pay and when they will pay. Customers have options.

Pricing Strategy

Finally, your pricing strategy, which is different from willingness to pay, may involve setting introductory low prices, or even offering your product or service for free. Indeed, in some cases, you might be willing to pay customers to use your product or service because you have other potential revenue streams like advertising or lead generation. At Facebook, for example, the company spent most of the early years attracting users rather than generating revenues. When the platform was large enough, Facebook could get advertisers to pay for access to highly targeted potential or existing customers.