Impact, Difficulty, and the Innovation Sweet Spot

Develop: An Experimentation Mindset - Idea Selection and Evaluation

The next phase of design thinking, Develop, will begin with the critique process that focuses on combining ideas into combined, testable solutions.

Learning Objectives:

- Explain how to begin evaluating innovation ideas in terms of feasibility and viability

- Define the near-far-sweet model and the impact-difficulty matrix

- Apply tools to change the feasibility of an innovation idea

In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy struck New York City. Parts of the city flooded, and millions lost power, causing the communication systems that people relied on, particularly their smartphones, to fail. It was an older technology, pay phones, that allowed many residents to make life-saving 9-1-1 calls after the storm. For the first time in decades, people were lining up to use a communication device that many considered obsolete.

After the city recovered, these experiences with pay phones caused leaders to pay more attention to the value of that infrastructure. They wondered, could pay phones be reimagined for the 21st century? Here, you will hear from designers who tackled this question and how they used tools from our next phase of design thinking, the develop phase, to address it.

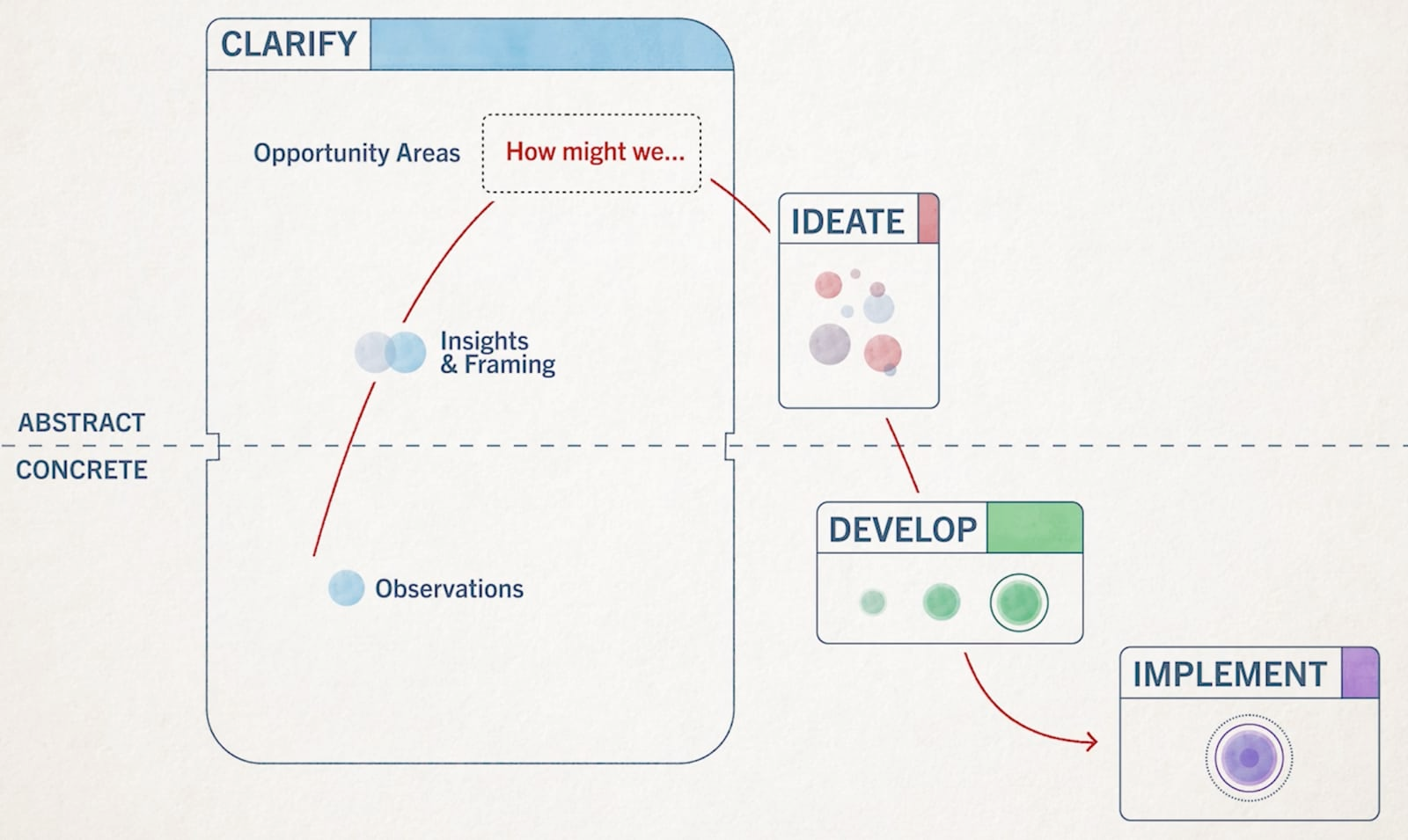

The develop phase has three complementary parts: idea selection, evaluation, and prototyping. These parts support and build on one another, but they are not necessarily linear. For example, you may combine ideas into a well-received concept, but prototyping may reveal a critical flaw in your new product, service, business model, or strategy.

Just as design thinking as a whole is non-linear and iterative, so are these parts of the develop phase. As you will learn, it is important to evaluate concepts and create prototypes early and often so that you can foster an experimentation mindset and develop tested solutions that are ready for implementation.

Before you make a model of your innovation idea, you should take the time to closely examine the results of ideation. Just as you made sure you were defining the correct problem in the clarify stage, you now want to make sure you are prototyping the correct innovation concept.

In the following video transcript, members of the Frog Design consultancy explain why they were attracted to solving the pay-phone innovation problem in New York City, and why a diverse team is valuable in imagining a complex new offering.

ADAM WRIGLEY: You walk down the street in New York, there are pay phones everywhere. Something like 10,000 locations of pay phones still on the street. As a New Yorker, they’re sort of iconic. And then we have the old iconic phone booths. You don’t often get a chance to design a new icon.

JONAS DAMON: It’s about people, it’s about communication, it’s about the city, it’s hardware, it’s software, it’s a service. This looks like a perfectly frog-shaped program to address.

LISA SCHEIRING: The premise of this was redesigning a pay phone and reinventing a pay phone. But is there really a need for a pay phone going forward? We all have devices that we carry around with us every day. So it was really changing the value proposition of a device on the street to be the future of communications and community communications within cities, and thinking about how that device on a corner could provide value in broader ways for a community.

ADAM WRIGLEY: And it was right around the time of Sandy that pay phones actually became a huge use during that. All of a sudden, they were being used more than they ever had in years because no one’s cell phones were working.

JONAS DAMON: Nobody, I don’t think, expected to be caught off guard like that, where you have no power, no communication, right in the middle of New York City in Manhattan.

TURI MCKINLEY: There was a very tangible sense of real on-the-ground research with the Beacon project, because we had lived through Sandy, we’d done work with FEMA to think about what are the needs, how does the city change when it’s in crisis. So we saw ourselves as part of the user base of this.

JONAS DAMON: We had some industrial designers, a mechanical engineer, software technologists, strategists, and a design researcher available—a whole group of people. Sort of the diverse team that you really need to think about something as interesting and as complex.

TURI MCKINLEY: So you get a bunch of people internally who are curious, engaged, and really kind of our thought leaders. And they came together to come up with the initial idea of the Beacon project.

ADAM WRIGLEY: We had the design concept out there. It got a lot of press. A lot of people actually came to us. And we designed this for just a design competition for the city. But fairly soon after that, they actually had a request for proposals from everyone for literally replacing all the pay phones.

Evaluating and critiquing ideas can be useful for all the reasons listed here: it may help you reduce costs, save time, increase the quality of the final innovation, and acquire additional observations and insights. Different reasons may take priority, depending on the context.

Many of the tools introduced here are idea-selection tools. Whenever you ideate, you will have numerous ideas to evaluate—and combine.

When you conclude an ideation session, you may have 40, 80, or hundreds of ideas for addressing an innovation problem. You have performed a preliminary evaluation through the Function Follows Form principle, and you can now combine these ideas into testable concepts.

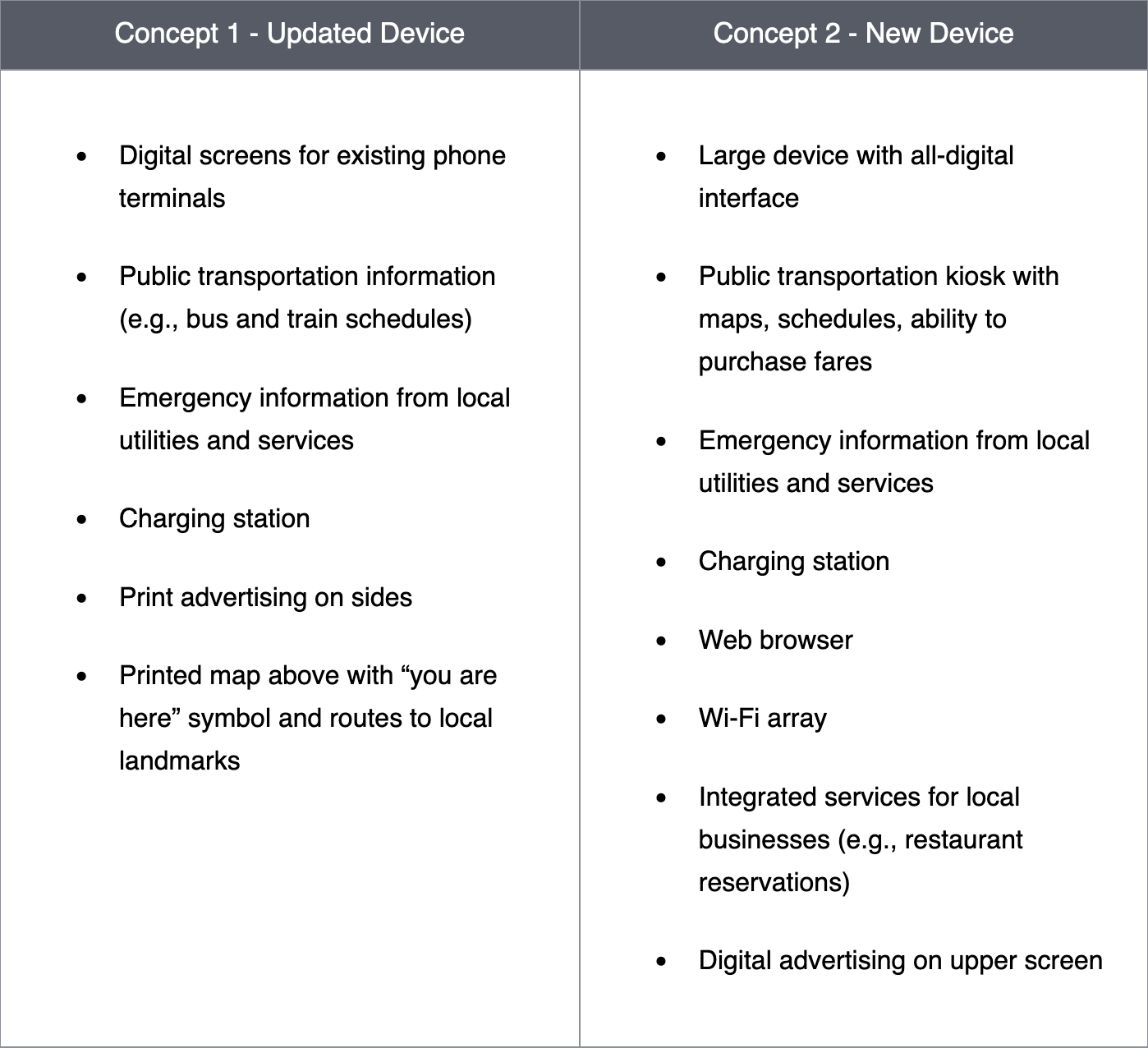

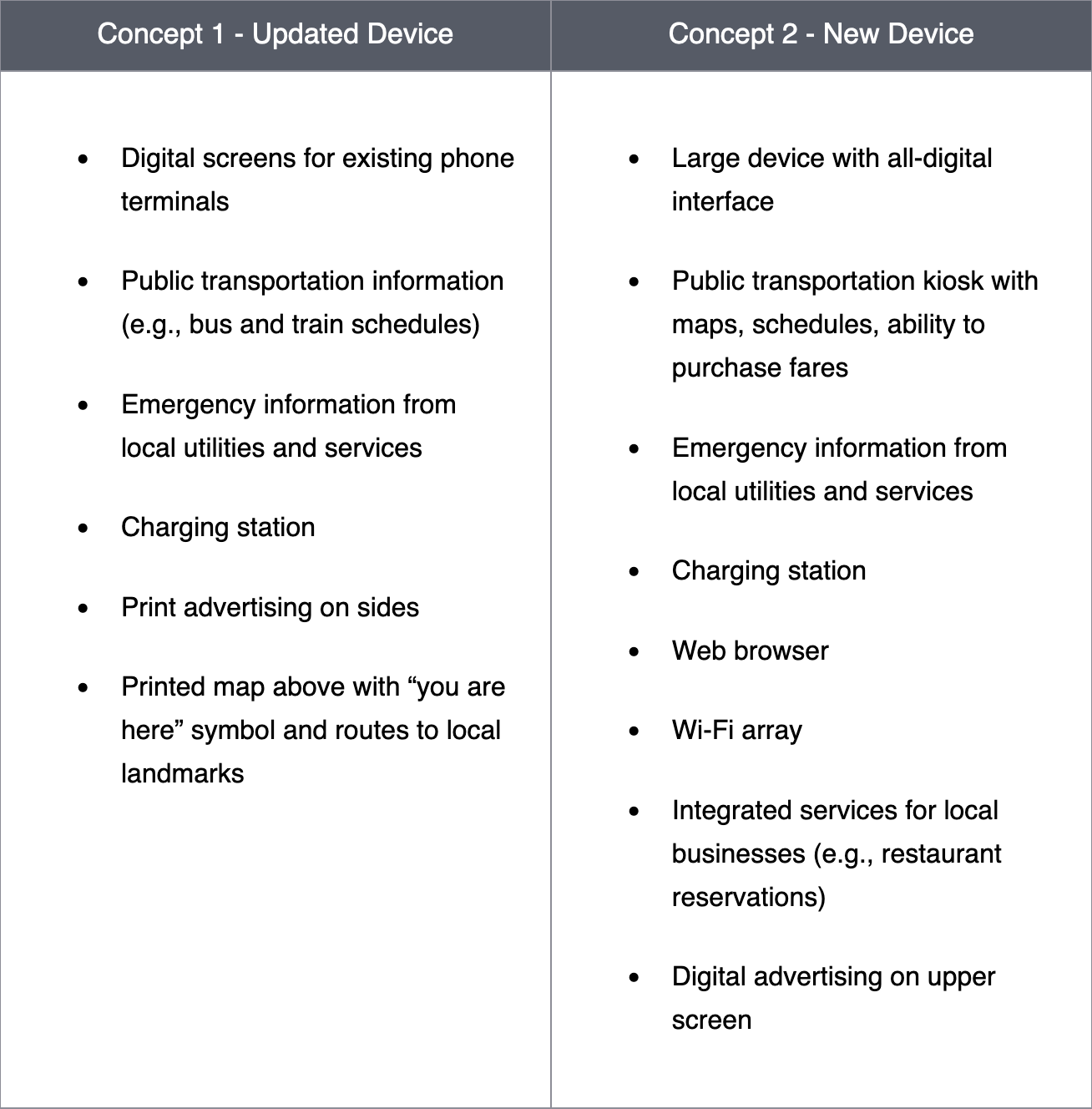

Experimenting with different combinations of ideas is an important part of evaluating the right path forward. For example, the following are two basic concepts for the redesign of New York City pay phones.

At this point, I want to clearly define two terms—ideas and concepts. The results of your ideation work are ideas. For example, your casual brainstorming may have resulted in ideas, like a digital interface, a Wi-Fi hotspot, or a kiosk for making calls and paying for public transportation.

When you combine ideas, you have a concept. This is when we switch to truly convergent thinking. What combination of ideas will best meet user needs? How do we begin to compare these concepts? Think of the iPod, Apple’s disruptive innovation in the music world. It was not one idea but many. The portable player, the distribution model via iTunes, the ability to purchase individual songs as well as whole albums, and even the player’s minimal interface—these ideas together formed a strong concept. And importantly, some would be easier to implement than others.

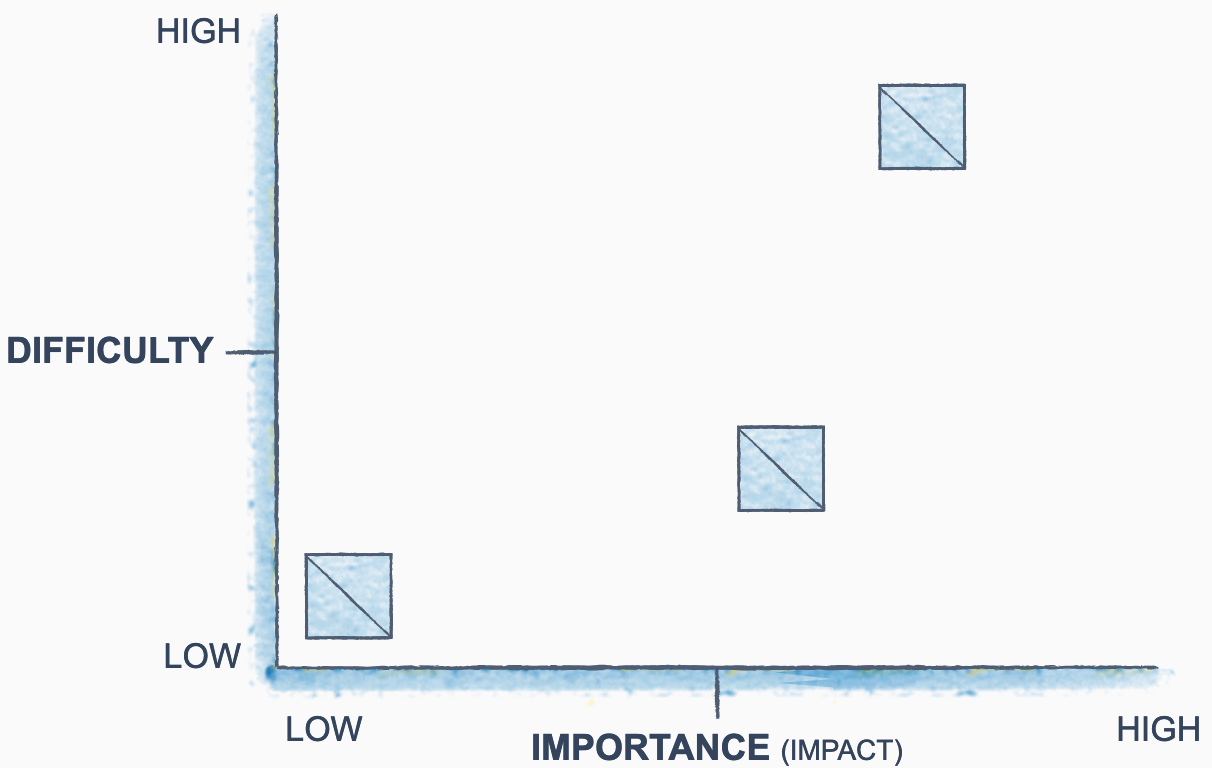

Let’s explore a tool that brings out these differences in ease of implementation—the impact-difficulty matrix. Adapted from a tool used by the LUMA Institute, the impact-difficulty matrix compares the potential impact of a concept against how difficult it would be to implement.

Creating the matrix is simple. You start with a horizontal line, then plot your concepts on the line from left to right according to how big of an impact they would have. In the pay phone scenario, for example, upgrading to digital interfaces would have a relatively low impact compared to transforming them into Wi-Fi hotspots that also provide local community services.

Once the x-axis is established, create the y-axis by raising up each concept according to how difficult it would be to implement. For example, we might raise the digital transformation idea up about halfway, but the full community Wi-Fi solution up near the top.

Ranking the possible impact of your concepts first and ranking their difficulty second allows you to quickly build a graph showing how the concepts compare in terms of strategy and implementation.

- Both impact and difficulty are subjective and dependent on context.

- You should rank each concept relative to the other concepts. All concepts may be impactful, but some will be more impactful than others.

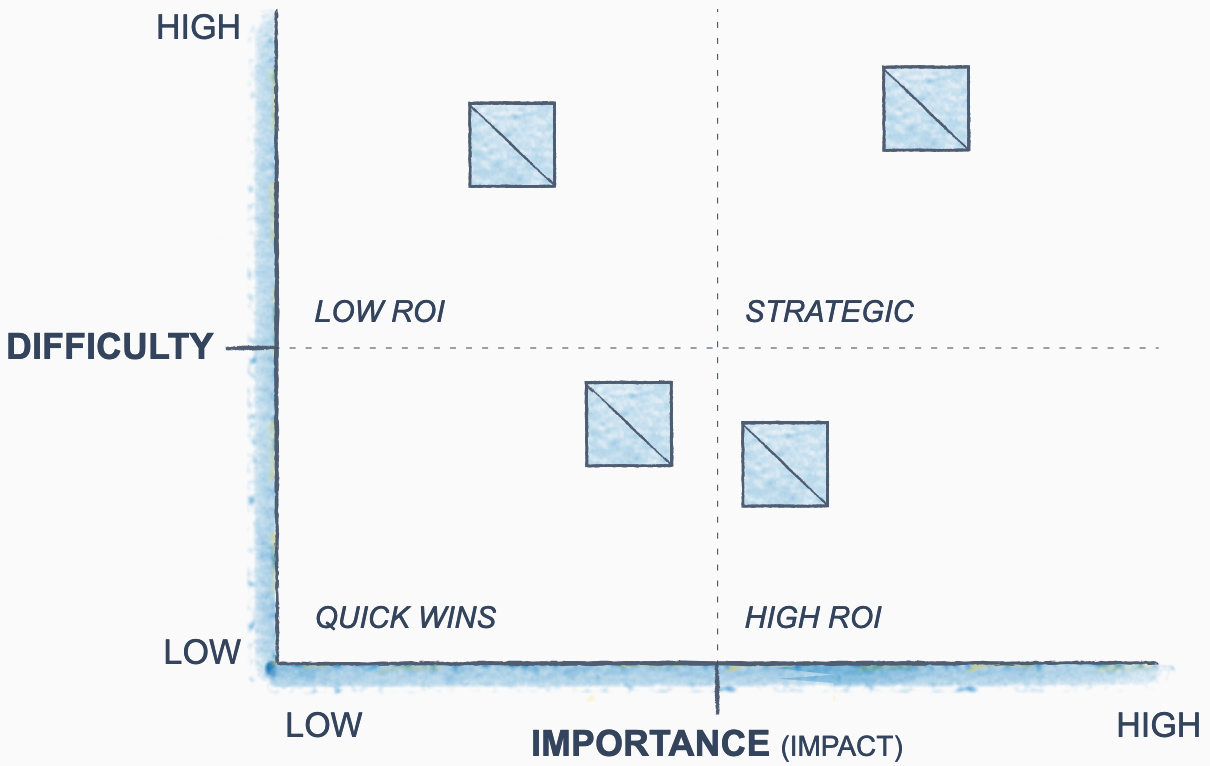

After plotting the impact and difficulty of each concept on the graph, you can divide the impact-difficulty matrix into quadrants. Each quadrant tells you something about the strategic advantages and disadvantages of the concepts within.

- Lower-left: Quick Wins

- The concepts in this space have a low impact but are easy to implement. They may offer positive short-term results, but they may also prevent the organization from considering more difficult options with greater potential impact.

- Upper-left: Low Return on Investment (ROI)

- The concepts in this quadrant have low impact and high difficulty. They are not worth pursuing.

- Lower-right: High ROI

- These concepts are ideal. They have high impact and would be relatively easy to implement.

- Upper-right: Strategic

- These concepts have high impact but would also be a challenge to implement.

Let’s return to the two example concepts for the redesign of the pay phone:

All rankings will be subjective, but remember that you should always rank your concepts relative to each other. For example, if you were ranking Concept 1 and Concept 2 independently, you might declare that they are both long-term strategic ventures to replace existing infrastructure.

By comparing the concepts to each other, you can note their strengths and weaknesses and analyze them more deeply. Concept 1 updates the existing terminals, but Concept 2 suggests constructing a new, larger device. Both concepts integrate public services like transportation schedules and emergency communications, but Concept 2 includes private partnerships with local businesses and the ability to purchase bus or train fares.

Because of these and other factors, one could argue that Concept 2 is more difficult and might have a bigger impact, and that Concept 1 is relatively a Quick Win. What does this mean for implementation, and how might we make Concept 2 easier to accomplish? We will explore these questions in the upcoming articles.