Improving Motivation and Ability: The Fogg Behavior Model

Ideate - User Values and Behaviors - Designing for Behavior Change

Learning Objectives:

- Describe how the Fogg Behavior Model plots the motivation and ability of populations

- Evaluate whether motivational sparks or ability-focused facilitators are appropriate prompts for a population in the Fogg model

We will continue building on Insigne Health...

Personas take much of the information you processed in the clarify phase of design thinking and turn it into useful profiles. These profiles are a first step in evaluating the desirability of the innovations you have created. They allow you to easily ask questions like, “How will each persona respond to our virtual product?” and “Does the product solve the pain points of this specific group of users?”

- Lack of knowledge about current exercise and nutrition choices

- Healthy habits seem boring or uninteresting

- The status quo feels adequate

- Stress reduces mental capability to create wellness plans

- Friends and family don’t model healthy choices

- There isn't enough time for family, work, and health

Let's categorize these pain points as behavioral scientist BJ Fogg would in his behavior model. As you will learn, “ability” has an expansive meaning in the Fogg Behavior Model, including not only physical and mental capability, but also resources like time, money, or even the willingness to stand out from the crowd. Similarly, motivation is aligned to specific binaries like hope and fear, and pleasure and pain.

Motivation:

- Friends and family don't model healthy choices

- The status quo feels adequate

- Healthy habits seem boring or uninteresting

Ability:

- There isn't enough time for family, work, and health

- Lack of knowledge about exercise and nutrition choices

- Stress reduces mental capability to create wellness plans

Ultimately, Elizabeth Quinby’s team had to provide recommendations for how Insigne could engage the Silent Middle. As she learned from her research, engagement would mean initiating change around one or more of the behaviors that drove chronic disease. These unhealthy behaviors included food and exercise habits possibly linked to disease (and often related to limited availability of healthier options), tobacco use, and excessive alcohol use.

Now that she knew who she was designing for, Elizabeth Quinby needed a system or model that could help her design for behavior change. After evaluating possible models, she began with the Fogg Behavior Model.

The Fogg model was created by BJ Fogg, the founder of the Behavior Design Lab at Stanford University. In the model, behavior is defined as a product of three factors: motivation, ability, and prompts. All three are needed to initiate and maintain behavior change.

- Behavior = motivation + ability + prompts

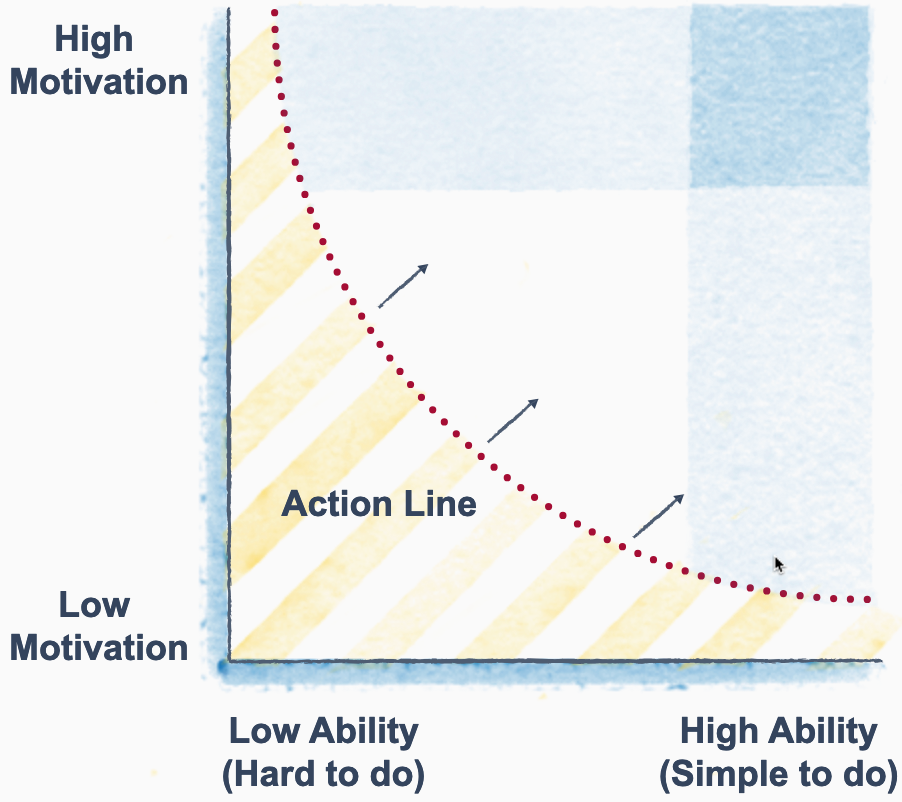

The first step of analyzing behavior in the Fogg model is graphing users’ ability and motivation along the x and y axes, as demonstrated in the following image.

Let’s learn more about the Fogg model’s first two components, motivation and ability, and how they are related to the “action line.”

The BJ Fogg Model centers on the action line, a curved dotted line running from the top left, where motivation is high, but ability is low, to the bottom right, where motivation is low, but ability is high. When users are above the action line, they are more likely to engage in a new behavior. They are also more likely to respond to prompts, which are cues to perform that behavior.

If users will not perform the behavior, however, then they are below the action line. Prompts will not work here because users don’t have enough ability or motivation to change how they behave.

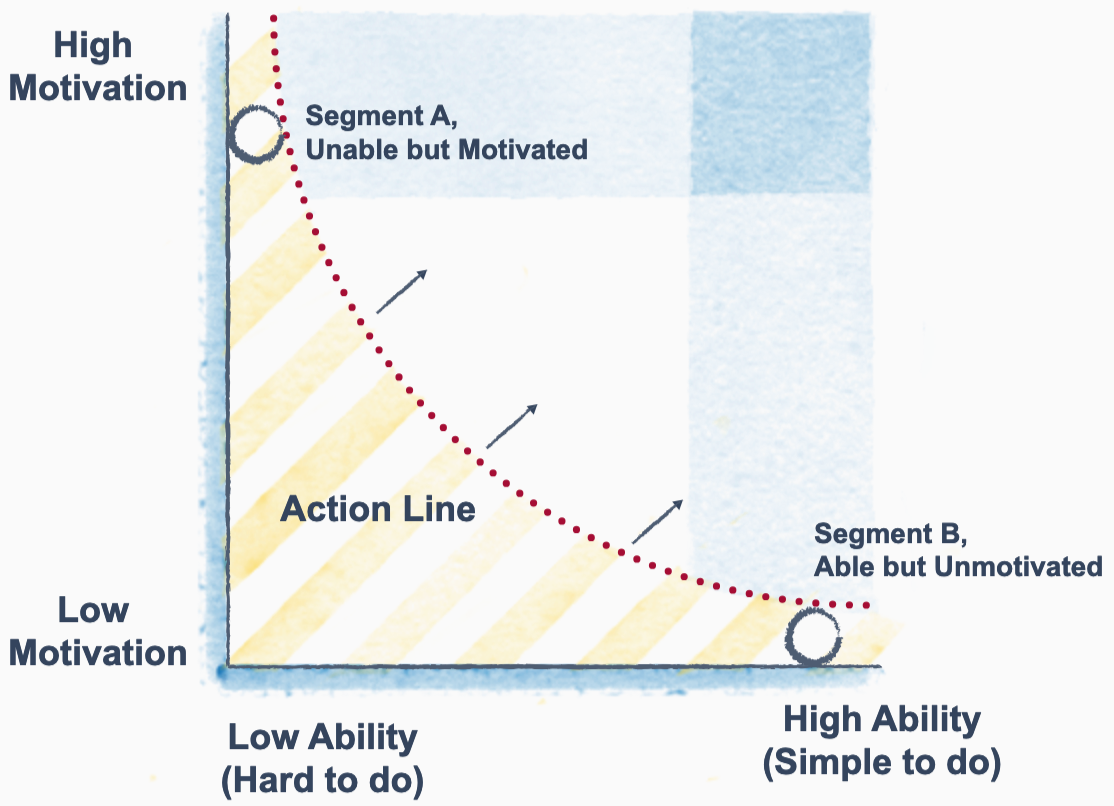

Let’s clarify by returning to our personas for the Silent Middle. Generally speaking, the people in Segment A have the motivation to engage in healthy behaviors. From their past experiences, they know the benefits of exercising, eating healthy, and avoiding tobacco. They want to live a long, healthy life for their families, but they lack the ability.

Ability is not just physical and mental capability. It can also be time, money, social pressure, or any other external factor that prevents someone from acting in a specific way.

Segment A (Unable but Motivated) is on the top-left on the Fogg Behavior Model graph.

Segment A has high motivation but low ability, placing them in the upper-left corner of the Fogg Model. Importantly, they would be below the action line because they’re not engaging with the app or performing the healthy behaviors.

The most common question is, how do I know exactly where someone is relative to the action line? The goal is to make the most reasonable estimate based on research and your understanding of the users. The Fogg Model is designed to inspire realistic conversations about where users are psychologically and how to allocate resources to inspire change.

Do users need more ability? Or do they need more motivation? If they need both, where should you start? If you’re more motivated to do something, it becomes easier to act. Conversely, if something is very difficult to do, you’ll need more motivation to overcome the challenges.

By identifying whether users already engage in the behavior and evaluating both their motivation and their ability, you can reasonably estimate where a user should be placed relative to the action line.

Now Segment B:

Each of these two user groups, Unable but Motivated and Able but Unmotivated, gets “hung up” on a different factor.

- Segment A (Unable but Motivated) has major constraints on energy, time, and other ability factors.

- Segment B (Able but Unmotivated) needs more pleasure, hope, or acceptance to increase motivation for their healthcare journey.

With this information, you proceed to the next step, which is asking:

What can I do to move users above the action line?

- If users are below the action line, prompts will only frustrate or annoy them.

- To establish the solid foundation for prompts to work, you must respond to users’ pain points related to motivation and ability.

Let’s start with Segment A, Unable but Motivated. This group of users is motivated to change, but they are limited in their ability. When we encounter the word ability, we often think of physical or mental capability, but “ability” in the context of the Fogg Model can mean so much more. In addition to physical and mental capability, what other factors might affect someone’s ability to adopt a new behavior?

BJ Fogg often refers to ability as being interchangeable with simplicity. He identifies several simplicity factors, including the following:

- The physical effort required to complete a task

- The thought or mental effort required to complete a task

- Time

- Money

- Compatibility with social norms

- Whether the task can be part of the user’s routine

Motivation is measured along three spectrums, with positive motivators more effective in the long term:

- Hope / fear

- Pleasure / pain

- Acceptance / rejection

When you wish to move users above the action line by boosting their ability or motivation, compare their pain points (from your personas or other research) to these simplicity and motivation factors.

- Ideas for Segment A to increase ability:

- Free healthy snack packs based on their interests (international foods, high-protein foods, sustainable or fair-trade products, etc.)

- Fun illustrations of quick stretches for workers who spend most of the day sitting or standing

- Ideas for inexpensive, healthy activities that can be completed as a family

- Ideas for Segment B to increase motivation:

- Weekly messages from healthcare professionals that emphasize patience and positive reinforcement

- Examples of realistic and attainable health goals

- A moderated community where people can share stories but avoid being exposed to negativity

Because Insigne Health is framing the problem as improving patients’ overall well-being, these ideas encompass work-life balance, mental health, and many other aspects of their lives.

These are simply ideas for discussion. Note that they are not prompts to engage in the desired behavior: They simply attempt to increase ability or motivation. Your focus must be on getting users above the action line—only then can you prompt them to engage in the behavior and reinforce it.

When users need equal help with motivation and ability to rise above the action line, BJ Fogg recommends starting with ability. As he correctly points out, it is simpler to make a task easier than to change someone’s internal motivation to complete it.

However, because ability is easier to improve, there’s a temptation to focus solely on ability. While this may help initially, remember that even users with high ability can fall below the action line if they lose motivation.

In conclusion, you need a deep understanding of your users to bring them above the action line. To increase users’ ability, you must understand the context of their lives. Their daily routines, environments, relationships, and time commitments are all relevant to their ability to complete an action. Similarly, to increase users’ motivation, you need to understand what drives them psychologically.

If your first attempts to convince users to adopt a new behavior fail, return to your research and look for new insights that might affect their relationship to the action line.

As you generate ideas for behavior change, review the focus of your results. Are you focusing too much on ability? Because we tend to think of making the task easier first, motivation is often an overlooked source for truly novel ideas.

In the following video transcript, Christi Zuber explains how the Fogg model changed her perspective on users’ psychological needs.

Around 2007 probably, I was at a conference, and BJ Fogg was speaking there. He was talking about the work that he was doing in behavior change. And long story short, I followed up with him after that, and he said he was just beginning these boot camps. And I asked, could I bring my team—because I have a core team of—there are 12 of us—to your boot camp?

And it was great, and we learned so much. And it really started to impact the way that we looked at the work that we were doing. And I think we were underestimating things, as you often see in health care industries and other industries of—if we just give people enough information about what this thing is, then I’m sure that they’ll do it because we are rational beings.

And we could list off on 40 pages all the reasons that you shouldn’t smoke, for example, give them out to people, and if they just read it, if they just look at it, clearly the evidence will be strong enough where people are going to stop smoking. We’ve, I think, approached behavior change that way for hundreds of years. Give people the information, and then they’ll do it.

And so it really started shifting in us at that point of saying, oh, well, there’s much more to it than providing information, which we knew. What kind of motivation do they have to do it? Is it very high? Is it very low? Does it change over time? Are we asking them to step out of our setting and go back into the real world and do something that’s really difficult? And do we think we’re setting them up for success when we do it that way?

So it made us really reflect and think about our interventions and our solutions in different ways and how we break it down and how to celebrate smaller successes because I think, like many people, we want things big and bold. And we’re in the innovation space. This needs to be huge. And it really made us reflect and say, really what it needs to be is impactful and sustainable. So huge isn’t the outcome. Impactful and sustainable is. And that can be achieved in many different ways.