Insights and Problem Framing

When you have collected and organized observations, you can analyze them for insights - these can be overlooked pain points, latent needs, or even new ways to frame the problem. Insight is the revelation of a novel perspective. It is an experience closely connected to creativity and problem-solving.

We covered the Observations part of the Clarify phase in the concrete space, and in this article we are going to talk about Insights & Problem Framing in the abstract space of the Clarify phase.

From Observations to Insights

We will define insight and use user research and pain points to generate insights and possible solutions.

To demonstrate, we will explore the T Puzzle, which asks you to construct a capital T using four specific shapes.

T Puzzle

The T Puzzle is a classic dissection puzzle where the goal is to form the shape of the letter “T” using a set of specific pieces. Typically, it involves four distinct shapes that can be arranged in only one correct way to create the “T” shape. The challenge is to figure out how to position these pieces correctly, as they often seem to fit together in multiple ways that don’t quite form the desired shape.

Key Characteristics:

- Pieces: The puzzle usually includes four pieces of various shapes, each with straight or angled edges.

- Objective: Arrange the pieces to create a perfect “T” shape.

- Difficulty: Despite the small number of pieces, the puzzle can be quite challenging and is known for requiring spatial reasoning and trial and error.

The T Puzzle is popular for problem-solving exercises and is often used to teach spatial awareness and logical thinking. It’s a fun, compact puzzle that offers a surprising level of difficulty given its simplicity.

The T puzzle appears simple because there are only four pieces. However, most adults struggle with it. In one study, no teams solved it within 5 minutes, most took up to 30 minutes, and some even declared it impossible.

The key insight is that the five-sided piece cannot be one of the end points of the T, so it is the most important piece to start with.

Insights occur when we recombine knowledge (the maps in our brains) in a new way, breaking through blocks to a desired mental path.

Insights can be acquired in any circumstance, but there is a reason why so many stories exist of people reaching insights while taking a bath or going out for a jog. Shifting to a focused, low-pressure environment is often a good way to stimulate insights and creative thinking.

Some of you might point out that you feel the most creative when you are under pressure. While insights also occur in high-pressure environments, they are less likely to occur than we think.

Research shows that people overestimate the amount of creative thinking they do under pressure. When people are working long hours and juggling multiple cognitive tasks, it can be difficult to find the mental focus for insight.

Research and analysis are both challenging, but you can improve both of them with practice. We will begin to explore the best working environment for insight later. First, let’s practice converting observations into insights.

Let's complete a field work assignment. We are managers who need to increase the productivity of low-wage workers without raising wages and without incentive programs. These are obvious solutions, and we want innovative solutions based on observations and insights.

We must go out and interview three or four workers. These people can work at a restaurant, a retail store, or in any low-wage position. We want to learn these workers' pain points and then identify insights that could lead to innovative solutions. We will now have a chance to examine real examples of this work and create our own insights.

For this assignment, we interviewed technicians at a nearby pharmacy. The technicians’ main responsibilities were assisting the pharmacist, processing new patients, filling prescriptions, and closing the transaction with customers. There was also a customer-service element to their role.

The pharmacy technicians’ explicit pain points were the following:

- Interacting with angry customers

- Pressure from pharmacists to keep up with the backlog of prescriptions

- Repetitive work - taking orders, counting pills, and processing customers at the register

- Feeling worn down by the need to serve pharmacists and customers simultaneously

Remember that insights cut to the true nature of a situation. What insights do you perceive in this situation, in the form of latent needs or a new perspective? And what possible solutions could you imagine for improving workers’ morale - without raising wages?

Technicians have the following latent needs:

- They want to feel valued and respected.

- They feel smarter than the role, and underutilized.

With these insights, we could begin to imagine creative solutions:

- Allowing technicians to wear lab coats or another official-looking uniform

- Assigning specializations in certain aspects of the job, like inventory management or specific kinds of medication

It is important to record your ideas as they happen. Insights come and go quickly. You risk losing the creative impulse if you wait.

The ARIA Model, based on research and concepts developed by David Rock and Jeffrey M. Schwartz, identifies four steps related to the experience of insight: awareness, reflection, insight, and action.

To foster an environment where insights can occur, consider giving teams the time and space to explore ideas in these four stages.

- Awareness: Quiet the mind and simplify the problem as much as you can.

- Reflection: Seek cognitive control by reflecting on the thinking process itself and how you are approaching the problem.

- Insight: Allow time for thinking until you have a moment of realization.

- Action: Act immediately - writing your idea down, or sketching it out - before you lose the insight.

People devote their time to meetings because they believe it benefits the business - but they often overlook the toll this takes on creativity. Meeting for hours a day and juggling multiple tasks can prevent insights from occurring. Consider the following advice for engaging with the ARIA Model:

- Give people uninterrupted time to think on their own.

- Encourage everyone to share ideas ahead of a meeting.

- Discuss the results together in the meeting, and have one discussion at a time.

What is Problem Framing?

Let's see how problem framing affects the solutions generated in the innovation process. Another important component of insight in the innovation world is problem framing. Framing refers to the scope, context, and perspective of the problem you are trying to solve.

Problem framing is one of the most important steps in the innovation process because it affects the types of solutions we generate. If we don’t consider a problem from different perspectives, we may end up focusing on a limited number of mostly traditional solutions.

Examine the following image of a kettle:

Imagine that you are frustrated with how long it takes for water to boil for your tea in the morning. How would you frame this problem in question form? Use this format: “How might we...”

How you frame the problem, based on observations, has a significant impact on the ideas you will generate for a solution. Let's analyze the tea-kettle problem and broad the approach.

The people who designed this kettle found that it was taking too long to boil water. And people were in a hurry. They wanted to boil the water faster.

As you look at this kettle, just think about different ways in which you might be able to change the design so that you can boil water faster.

If you discuss this with people, you will see that intuition pushes us to adopt a narrow framing at first, such as “How might we improve the power of the coil?” This leads to ideas about improving the size of the coil or increasing its power.

However, another way to frame the problem is, “How might we get more heat into the water?” This question seems similar, but it is actually much broader - it opens up possibilities beyond the coil itself. For example:

- Changing the shape of the kettle

- Preventing bubbles of air from insulating the coil

Finding New Problem Framings

We will now see how to:

- Apply “how might we” question starters to a variety of business situations

- Identify the criteria for productive problem framing

Most of the time, knowledge and expertise have enormous value in problem-solving situations. But when we need to challenge our usual ways of thinking, they can be an obstacle. This is because education and experience lead to the creation of patterns of thinking that can be hard to disrupt.

A good way to practice reframing problems is to use "How might we?" questions. This means simply rephrasing a problem from a different perspective using a question that begins with the phrase, "How might we?"

For an everyday example, imagine that a child is constantly late for school. The initial problem is, "We need her to get to school on time." But we could reframe it as, "How might we ensure everyone wakes up early?" This shifts the focus to additional people, time frames, and activities. The goal is to encourage discussion from a different perspective.

Many creative organizations such as IDEO and Google encourage the use of “how might we” questions, but the process was first defined by business creativity researcher Min Basadur. It is readily applicable in a variety of business contexts. For example:

- We need an app that helps people understand their 401(k) options. → How might we ensure that no one regrets their financial choices after they retire?

Reframing helps in two ways. First, it helps you tackle a broader spectrum of pain points. Second, reframing opens up possibilities for new ideas - including ones that would be considered “out of bounds” in traditional framings. For example:

- “How might we ensure that no one regrets their financial choices after they retire?”

- This framing expands the journey map to consider additional pain points related to lifestyle, family, and customers’ relationship with the brand both leading up to and after retirement.

- It leads to broader ideas, such as data modeling that compares all fund options to lifestyle goals.

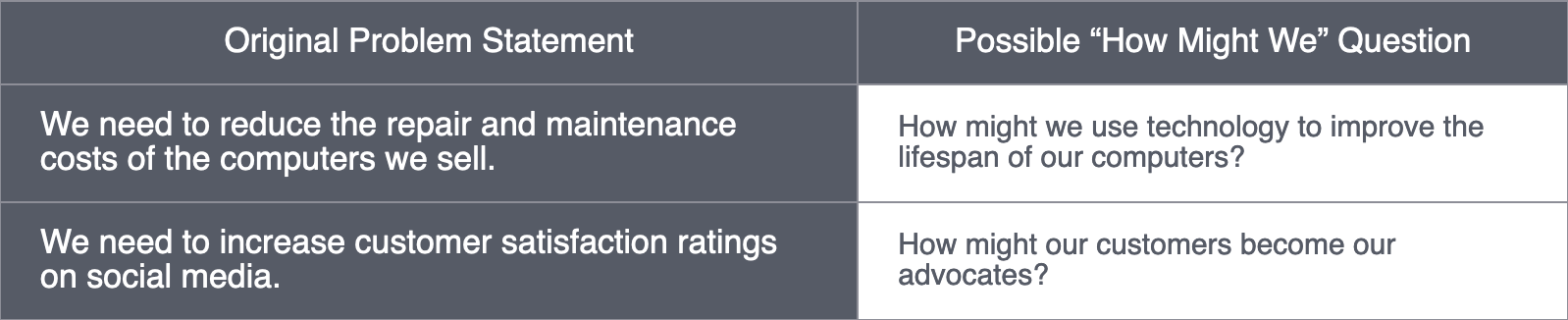

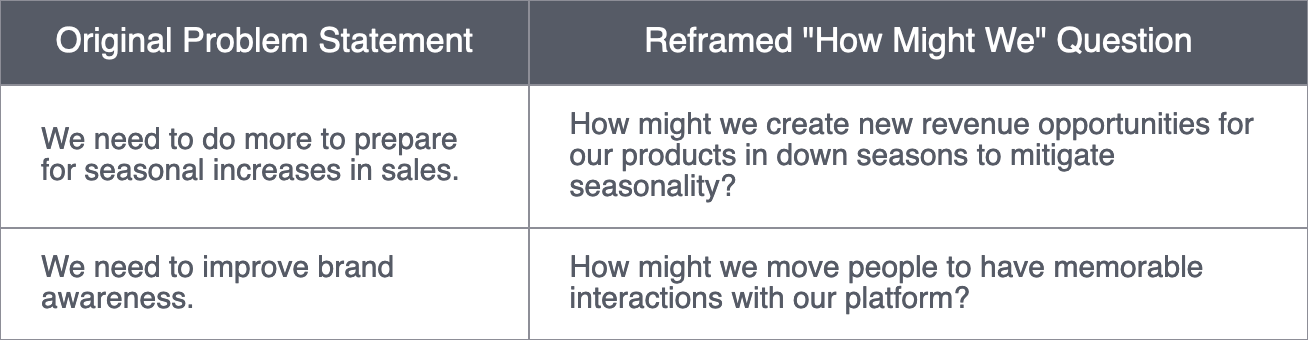

Let's see some broader “how might we” questions for the following problems:

The following are examples of multiple framing evolutions in Amazon’s strategy and business model:

- Strategy: Amazon frequently reframes the strategic problems it is trying to solve.

- How might we sell books online? → How might we sell other products online? → How might we use the technology we have developed for other purposes?

- This is how the infrastructure for selling books evolved into Amazon Web Services.

- Business Model: In traditional retail, Amazon continues to reframe processes around research into customer needs and behaviors.

- How might we reduce checkout costs when shopping? → How might customers check themselves out? → How might we eliminate the checkout process altogether?

These new framings allowed the organization to successfully challenge assumptions about how assets and processes should be employed. Ideas that might sound illogical from an operational standpoint - like an online book retailer selling cloud computing solutions as well - become possible when you consciously reframe for innovation.

One good test of reframing is whether you can generate new ideas in response to the new pain points and latent needs that come into focus.

Consider the original problem statements and new framings in the following table.

Do you think the new framings are broad and would lead to interesting new ideas? Why or why not?

“Broad” is only one characteristic of potentially innovative problem framings. There are four ways to approach an innovation problem from a new perspective: deep, emotional, broad, and dynamic.

- Deep rather than shallow: Does it offer a deep examination inward toward the finer details of the problem?

- Shallow statement: How might we increase sales of items in our online store?

- Deeper statement: How might we understand each customer well and serve products they are more likely to buy?

- Emotional rather than only functional: Is there a personal component to the question based on user research or observations?

- Purely functional statement: How might we increase customers’ willingness to buy environmentally friendly but more costly products?

- Balanced statement: How might we make customers feel good so that they see more value in environmentally friendly products?

- Broad rather than narrow: Does it shift the focus to a larger context or scope?

- Narrow statement: How might we change our compensation package to attract talented candidates?

- Broad statement: How might we create an exciting environment to work in?

- Dynamic rather than static: Does the framing build from unusual or interesting observations, or encourage wild solutions?

- Static statement: How might Apple improve the performance and market share of the Macintosh brand?

- Dynamic statement: How might Apple use digital computer capabilities to create an entirely new market for digital music?

Reframing to Find the Most Interesting Problem

Let's see how to:

- Apply a new framing to an innovation problem and explore the results

- Explore an innovation problem using the webbing tool

In addition to the four characteristics of innovative problem framing - deep, emotional, broad, and dynamic - there is another aspect of effective framings to explore.

Consider the following four problem framings. What do they have in common?

- We need to increase customer satisfaction ratings on social media.

- We must reduce shipment delays related to quality issues in the supply chain.

- How can we increase security against phishing attacks?

- What can we do to prepare for seasonal increases in sales?

The most important similarity is that all of these problems are anchored in the status quo. If your thinking is based on the existing context, your solutions will probably be limited and not truly transformative.

With that in mind, this is the final characteristic of an innovative problem framing:

- It should identify the most critical, interesting, and game-changing part of the problem.

To see how this works in action, let’s consider the case of a premium wine producer in California’s Napa Valley.

It's September and nearly harvest time at the Freemark Abbey Winery in Napa Valley, California. A storm is approaching the winery. The vintners here have a difficult decision to make. Usually, they would leave the grapes on the vine to ripen for a few more weeks, but the storm makes that risky.

Freemark Abbey is a major producer in Napa, including Riesling wine. This close to harvest, a storm could be bad for Riesling grapes. They are sensitive to temperature, and a cold shower would decrease the quality of the resulting wine or possibly even ruin the crop.

However, there's an interesting twist. If the storm brings a gentle, warm rain, it will actually make the resulting wine even better than usual. This type of rain can cause Riesling grapes to grow something called botrytis mold. This mold concentrates the sugars and gives the wine a more complex flavor. Wine connoisseurs pay a premium price for botrytis Riesling. If the Riesling grapes end up getting botrytis, the winery would gain significant prestige and profit with a price more than double the usual amount paid per bottle.

With the storm approaching, the vintners have to decide. According to weather reports, this storm is coming from warm waters, so there is a 40% chance that it will be the right kind of rain for botrytis. This would result in doubling their profits. Or they could harvest the grapes now, avoiding the risk and collecting an average crop.

And there are additional options Freemark Abbey could consider, such as bottling the wine under a different brand name if the rain has a negative effect on the grapes, or even selling the grapes or the wine in bulk.

There are many options for this simple framing of, "Do we harvest the grapes or not?" What would you do?

This initial problem framing focused heavily on short-term value creation and concentrated on maximizing the value of the harvest. You might have thought of harvesting a portion of the grapes to hedge your risk, or you might have thought of covering the grapes so you could continue keeping the grapes on the vine after the storm passes. Or you might have simply taken the chance and hoped you would get botrytis. You might have been guided by the additional benefit to the Freemark Abbey brand of producing a botrytis wine that would make you even more willing to take the risk.

However, the question to ask is, was this the most interesting framing? It produced a number of interesting solutions. And you would be pleased with these solutions if you were approaching the problem from a purely operational standpoint.

But we are approaching this problem from an innovation context. From that perspective, the framing did not address the most interesting part of the problem - the botrytis. Botrytis was the most game-changing part of the problem. And none of the solutions generated by focusing on the value of one harvest would have addressed how to get botrytis more often.

We should encourage debate around the original framing of "Should we harvest or not?" to highlight the danger of short-term thinking and how it affects our ability to frame problems in an innovative way.

Now that you know the more interesting problem framing - “How might we get botrytis more often?” - what alternative solutions could you imagine?

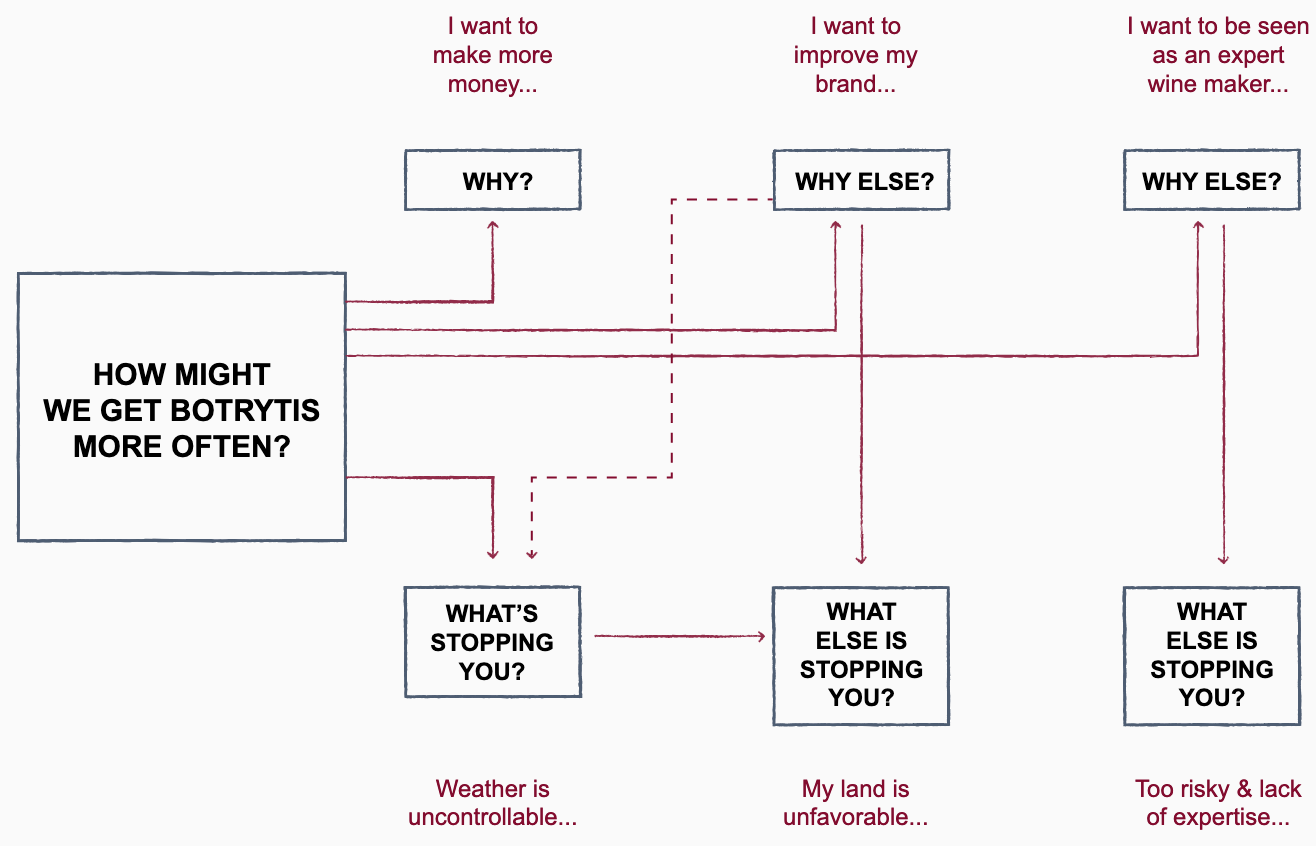

Let’s explore a simple tool called webbing, which was developed in this form by Gerard Puccio and others at the International Center for Studies in Creativity at Buffalo State University:

- Write your “how might we” question in the center of the page.

- Along the top, explore the reasons why you want to solve this problem.

- Along the bottom, answer the question, “What’s stopping you?” Why can’t you solve this problem now?

The following is a template for how the Botrytis question might be explored. As you answer “why” and “what is stopping you,” you can explore connections and different starting points for forming a “how might we” question:

The goal is to dig deeper into the reasons you want to pursue the problem, and what the imagined roadblocks are. Webbing organizes these thoughts in a way that encourages new problem framings.

Why would Freemark Abbey want to produce more botrytis wine, and what is stopping them from doing so?

The following are some possible answers:

Review the following webbing template for the botrytis problem.

Each of these answers could lead to more “how might we” questions. For example:

- How might we make more money?

- How might we improve the brand?

- How might we reduce risk?

- How might we get more favorable land?

For the partners at Freemark Abbey Winery, the most valuable insight was reframing the problem geographically. Are certain areas more likely to experience the correct rain for botrytis?

After conducting research, they learned that this was true. And after negotiating with another vineyard, they bought land and shifted their Riesling production to the preferred spot. This led to more frequent production of botrytis Riesling and more prestige for the winery.

There is an enormous gap between Freemark Abbey's original framing, "Do we harvest the grapes or not?" and the more interesting framing of, "How might we get botrytis more often?"

This example is effective because every design problem might have its own botrytis. A more positive and exciting framing can lead to an innovative solution.

Just as the storm's approach constrained Freemark Abbey's time to make a harvest decision, businesses feel enormous pressure to produce results. And those constraints on time can block your view of what the real long-term problem is.

You as business owners and managers will inevitably encounter pressure and operational complications. If your goal is innovation, you will need to navigate these difficulties in two worlds - the operational world and the innovation world.

If issues are approached from a purely operational mindset, you may be tempted to jump to the easiest and seemingly the safest solution. You then solve one operational problem and then move to the next. This is sometimes a good strategy.

But if you can cross over to the innovation world and reframe from that perspective, you convert an operational problem to an innovation problem and gain valuable opportunities to revise your approach and develop unexpected solutions.