Introducing Insigne Health

Ideate - User Values and Behaviors - Designing for Behavior Change

Learning Objectives:

- Identify pain points for a user group in the Insigne Health case

We will discuss behavior change in the context of the health insurance industry. Insigne Health is a composite case written to represent the general experiences of organizations that are both insurers and health care providers.

According to the details of the case, Insigne Health has operated in the United States for 20 years. As both payer and care provider, Insigne made prevention a key part of its strategy. Prevention was and remains crucial to keeping health costs down. After the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, which made coverage for many preventative services mandatory, Insigne decided to put even more support behind prevention. For example, they eliminated co-pays for most screenings and created incentives for clinicians to coach patients on prevention. These efforts resulted in a significant increase in prevention screenings and treatments.

But Insigne wants to go further. They aim to redefine what health insurance means to patients. Instead of merely being a solution for sickness, Insigne wants people to think of insurance and health care as an ongoing process of maintaining well-being. This shift in traditional problem framing calls for a new approach.

Caroline Hodgman, the VP of Member Engagement at Insigne Health, led the launch of an app called Health Tips. In addition to providing information about healthy behaviors, Health Tips tracks users’ progress in an incentive rewards program, offering prizes for engaging in those behaviors. Caroline Hodgman was particularly interested in research showing how healthy and unhealthy behaviors could spread through networks of social connections. The app was designed to leverage these connections through social features.

While the launch of Health Tips was partially successful, Hodgman suspected that the patients actively engaging with the app were the members Insigne was least concerned about in terms of future costs. To address this, she hired Elizabeth Quinby, a partner at Hamilton Strategic Design, a consultancy specializing in the health care sector. Quinby and her team were tasked with helping Insigne better understand its member base and uncover new opportunities for engagement.

While the launch of the HealthTips app was partially successful, Insigne Health’s Caroline Hodgman worried that the members engaging with the platform were those who would benefit least from prevention outreach: individuals who were already engaging in healthy behaviors, and individuals who were already addressing illness and illness risk with their care providers.

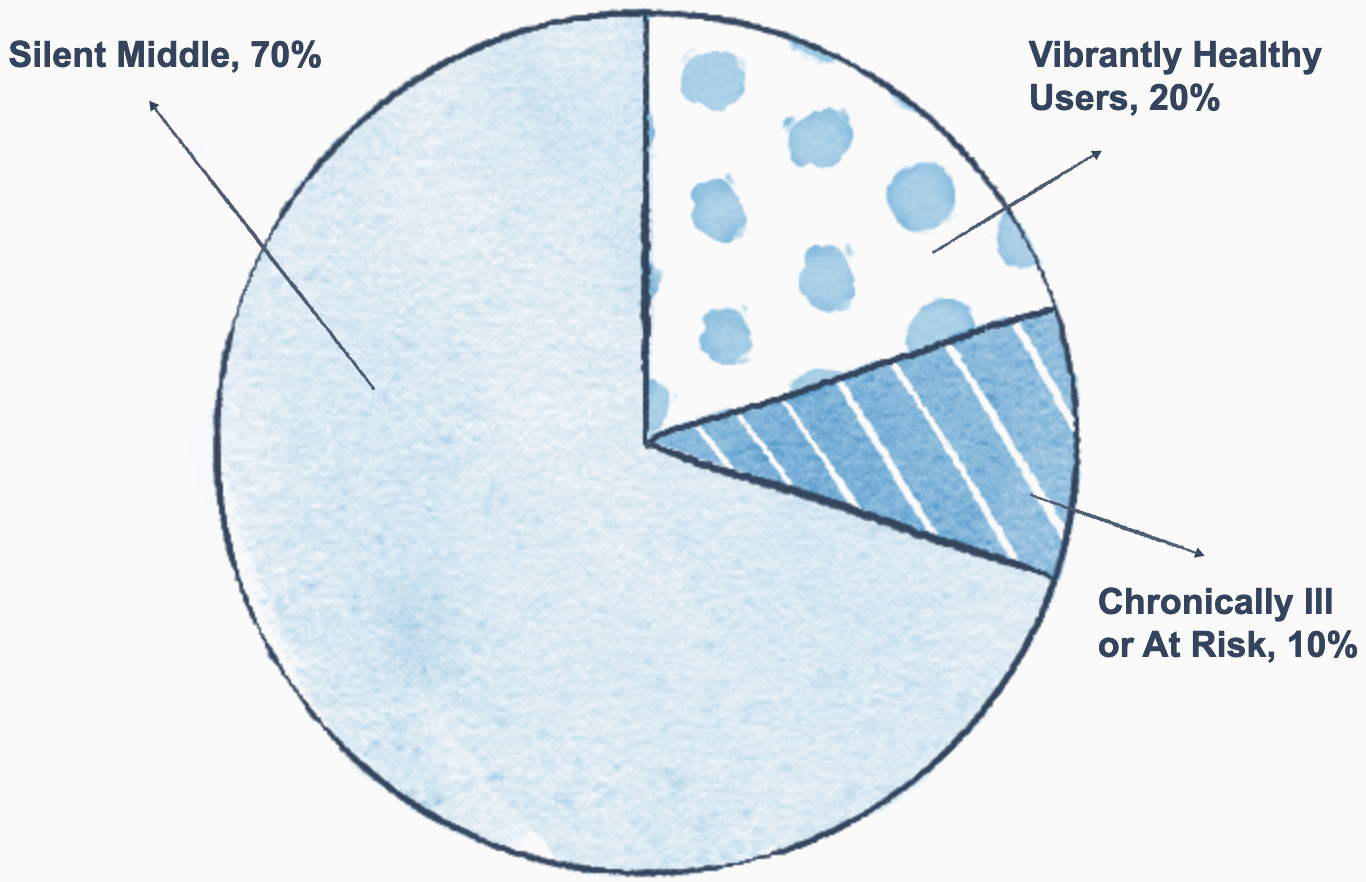

Insigne’s research confirmed that the two member groups engaging with HealthTips the most frequently were the 20% who were already in good health, and the 10% who were suffering from chronic conditions or at immediate risk.

The remaining 70% of members were not regularly engaging with the app—and while they were not experiencing chronic illness, they were not taking any steps to prevent the development of one in the future.

Insigne Health categorized the 70% of members not engaging with HealthTips as the “Silent Middle.” This majority of the membership was somewhere between healthy and chronically ill.

These were the members who would benefit the most from HealthTips. Members of the Silent Middle were not engaging in regular healthy behaviors, and some were actively engaging in unhealthy behaviors. Examples include:

- Not engaging in weekly aerobic physical activity

- Eating few fruits and vegetables

- Drinking large amounts of alcohol

- Smoking tobacco

As a result, the Silent Middle were at a higher risk of developing chronic conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure. However, they weren’t suffering from these conditions yet. In addition to the many other contextual reasons for these unhealthy behaviors, members felt little reason to change.

Insigne Health knew from research that the Silent Middle would eventually account for nearly 50% of their future health costs because of their likelihood of developing chronic conditions. If HealthTips could reach the Silent Middle and encourage them to change their poor health habits, Insigne could improve member health and significantly reduce costs associated with chronic disease.

In her research, Caroline Hodgman also learned that obesity rates among members reflected national averages, which meant they were increasing. This was another reason why the launch of HealthTips was so important.

In the case of Insigne Health and the Silent Middle, knowing exactly which members of the health insurance network to target was an advantage. Remember that the Look, Ask, Try framework from the Clarify phase encourages you to observe deeply, ask questions with an open mind, and try things for yourself.

In this case, researchers could have observed members’ daily habits and purchases. What did they eat? When and why? What behaviors did they choose instead of healthy ones like exercise? They also could have asked questions about the members’ daily mindset. How did healthy behaviors make them feel? Nervous and intimidated, or perhaps energized and joyful? Building rapport to understand their mindset would be equally important. Finally, they could try it for themselves. What would it be like to use the app during a busy lunch break or to fit in exercise at the end of a long workday?

Through research like this, Caroline Hodgman of Insigne Health would have developed a deep understanding of Insigne’s membership. However, she also recognized the tremendous value in bringing outside perspectives and capabilities to a problem. She had worked with Elizabeth Quinby in the past, and Ms. Quinby’s research had led to actionable insights.

Now, think about the times you or your organization asked for outside help. Why is this valuable? One reason is that you’re often so close to a problem that you can’t see it clearly. Additionally, teams may focus on the pain points in their own workflows and prematurely rule out ideas as too difficult without fully considering them. An outside perspective counteracts this by presenting situations in a new light, and it may help teams feel they have permission to pursue more difficult options.

To facilitate new opinions and ideas, Caroline Hodgman brought in Elizabeth Quinby and her strategic design firm to work on the problem. While it was an advantage to know the target population, Elizabeth Quinby also faced challenges that were specific to engaging the Silent Middle, such as:

- These members rarely interacted with their care providers.

- They spanned all ages and demographics.

- They did not share many characteristics beyond health-related factors (such as the amount of daily exercise).

- Their motivations were different.

When Elizabeth Quinby conducted research, she sought to identify patterns that would segment Insigne’s Silent Middle according to their shared pain points, what they valued, and what drove their behaviors (i.e., their motivators).

She started by analyzing why Insigne’s current strategy might not be working. Insigne’s offerings for preventative care were generous. For example, there were discounts on gym memberships and workout equipment, and rewards programs for hitting dietary goals. Elizabeth Quinby contacted Insigne’s healthcare providers first to ask for their perspectives on why patients weren’t taking advantage of these preventative care options.

Elizabeth Quinby held interviews with healthcare providers across the care spectrum, from primary care physicians and nurse practitioners to specialists treating patients with complications from their chronic diseases. The research team heard concerns about the same problem again and again: Why aren’t patients doing more to protect their health?

Think about the guidelines for good problem framings from the Clarify phase. Good problem framings should be deep, broad, emotional, and focused on the most interesting part of the problem.

One critique of the original framing is that it puts the responsibility for improvement entirely on patients, which isn’t a good perspective for meeting users where they are. A different framing, like “How might we make patients excited about changing the habits they can change?” would result in a different approach to interviews and ideation.

Healthcare workers would be an excellent source of insight into the beliefs and motivations of the Silent Middle. Dr. Christi Zuber was once a nurse and then a director of innovation for the healthcare organization Kaiser Permanente.

Because of her experience in the healthcare field, she offers a unique perspective on innovation in healthcare systems. In the following video transcript, Christi Zuber explains why healthcare and innovation can be a natural fit:

In terms of my role as a nurse, I had this really funny moment at one point. I was standing on stage at a large conference, and I remember looking out into the crowd. It was a conference about innovation, health care, and design. I thought to myself, I don’t know that the 20-some-odd-year-old nurse in me could have ever imagined what I’d be doing now. Back then, I didn’t even know that design thinking, human-centered design, or innovation practice was a thing.

But as a registered nurse, what I did know—like every other nurse—was how to understand a problem and how to creatively address it. Nurses are often described as masters of workarounds. They’re creative, nimble people, often because they have to be. The systems they work within don’t always provide everything needed to do their work effectively. So, nurses rise to the occasion, figure it out, and ensure that the patient and their family remain at the center of everything they do. For community or home health nurses, this focus extends to the individual in their home and community.

The human-centeredness of design thinking really resonates with nurses, and it certainly resonated with me as a nurse.