Open-Ended Approaches to Generating Ideas

Ideate - Tools and Frameworks for Generating Ideas

Creative Problem-Solving and Problem Stories

Learning Objectives:

- Identify what creative problem-solving means in the context of defining a problem

- Construct a problem story of undesired phenomena and practice reversing cause-and-effect relationships

As we have discussed, the SIT thinking tools are designed to be simple to apply. You apply the tools, create a virtual product, and then evaluate the results. This is the standard approach when following the Function Follows Form principle. Its simplicity is a benefit, as breaking fixedness is mentally challenging.

But what can you do when the root cause of the problem is difficult to define? What if, after extensive research in the clarify phase, it is still challenging to find a problem framing? In cases like this, we turn to less structured approaches that are more appropriate for open-ended situations, like creative problem-solving.

Creative problem-solving helps you address a problem without defining it. This approach is best used when you don’t know or can’t agree on the root cause of a design problem or issue, but you still have a clear endpoint in mind and know what the desired solution might look like. It focuses on processes in addition to the use of quick tools.

We introduce just enough structure and focus to generate desirable, feasible, and viable ideas. I like to describe this as a shift from tool-based to rule-based ideation. While there are still tools to apply, the emphasis is on developing new perspectives and fostering experimentation.

User research is always worth doing, because if you can find insights into the root cause of a problem, that gives you a significant advantage in the innovation process. However, in some cases, you may not have enough time to find the root cause of the problem.

Moreover, the clarify phase does not always produce a problem framing that everyone can agree on. Teams with multiple perspectives may not be able to find consensus. To someone in marketing, it will be a marketing problem. Operations, sales, and finance may all have their own ideas about problems and solutions.

When this occurs, one approach developed by SIT is to stop investigating the root cause and instead try to tell the problem story, which consists of a chain of undesired phenomena.

Imagine that you work at a major bookseller, and you have recently noticed a drop-off in sales among rewards members. Interviewing them, you find out that their lives are getting busier. They want to read more, but they are too busy running errands and balancing other work and home tasks.

Why is this a difficult user problem to find the root cause of?

Especially for a major bookseller with thousands of rewards members, the customer base is broad and diverse. The general pattern is that customers are too busy to read, but the reasons why they stop reading are too wide-ranging to pin down and address. For example, some may be too busy with young children, while others may be too fatigued from long hours at work, among many other reasons.

You can use original research or an existing journey map to create a problem story, which is a sequence of undesired phenomena (UDPs) linked by cause and effect. Both problem stories and journey maps help you identify opportunities for intervention.

Let’s explore how we might build a problem story for the reader example. We can start with any negative outcome. For example:

| The customer has less time to read. |

To go up in the chain, or forward in time, we ask the question, “So what?” Why is this a problem? What is the next possible negative outcome?

In this case, the customer has less time to read. It may then take them longer to finish the book, and they may lose interest altogether. Then, they don’t purchase another book they wanted to read.

| The customer doesn’t purchase another book they were excited about. |

| The customer loses interest in reading. |

| It takes the customer longer to finish the book. |

| The customer has less time to read. |

The problem story you develop might be different. That is OK. It is helpful to experiment with different problem stories. The point is that we built this chain up by asking “So what?”

To go down in the chain, or backward in time, we ask, “Why?” Why did this happen? What is the cause? Try this with the problem story we have just constructed:

| The customer doesn’t purchase another book they were excited about. |

| The customer loses interest in reading. |

| It takes the customer longer to finish the book. |

| The customer has less time to read. |

Expand this problem story one step “down” by creating a cause-and-effect event leading to “The customer has less time to read.” Ask “Why?” to generate this event.

In this case, why does the customer have less time to read? Perhaps the customer has become busy with tasks at home. You can read this problem story from top to bottom by asking, “Why?”

| The customer doesn’t purchase another book they were excited about. |

| The customer loses interest in reading. |

| It takes the customer longer to finish the book. |

| The customer has less time to read. |

| The customer becomes busy with tasks at home. |

We will soon discuss how to break this chain of UDPs, but first, review SIT’s guidelines for creating useful problem stories:

- Choose a random UDP to start the chain. Because you’re building out the chain in both directions, it doesn’t matter where you start.

- Ask “So what?” and “Why?” from the perspective of the problem owner, the person most affected by it. (In this case, we focused on the customer who loves reading, but you might also focus on the bookseller.)

- Each UDP should be one sentence, and each sentence should present only one UDP.

- There must be a cause-and-effect relationship between the UDPs.

- Make sure there isn’t a big gap between each pair of UDPs. Small gaps maximize the opportunities for breaking the chain.

A problem story can become quite complicated. Some UDPs might split off into different branches, for example. For now, we will stick to the basic linear structure.

Let’s apply the problem story to another business-oriented situation. Imagine you are a manufacturer. Your customers are fickle, and to ensure that you’re able to meet their needs, you maintain large inventories of various products.

Can you create a problem story for this manufacturer? Remember, to move up the chain, ask “So what?” To move down the chain, ask “Why?” Try to include at least four UDPs in your response.

Review this sample UDP chain:

| I have lower profits |

| I have a high cost of inventory |

| I have high inventories of different products |

| Demand is highly uncertain |

| Customer preferences are fickle |

Once you have a problem story, you can focus on breaking the chain. The first step is to pick two UDPs that are next to each other. This should represent a direct cause-and-effect relationship. You can visualize it as a graph, with the earlier UDP on the x-axis and the later UDP on the y-axis.

Next, describe the existing situation as it would appear as a line on the graph. For example, the more uncertain the demand, the more inventory I will need to keep. In this case, the line ascends from the lower left to the upper right because it reflects a positive relationship.

Once you have described the existing situation, you can begin experimenting with qualitative change through one of two methods: inversion or neutralization. This involves asking two questions: Can I change this relationship so that the opposite occurs? Or can I completely neutralize this relationship?

In inversion, the cause remains the same, but the effect is reversed. For instance, what if the more uncertain the demand, the less inventory I needed? Neutralization, on the other hand, eliminates the cause-and-effect relationship entirely. For example, what if the more uncertain the demand, the less it bothers me because nothing happens?

Inversion means reversing the cause-and-effect relationship, while neutralization eliminates the cause-and-effect relationship entirely.

We start by selecting two adjacent UDPs. For example, in the problem story for the bookseller, we could select “The customer becomes busy with tasks at home” and the UDP immediately above it, “The customer has less time to read.”

The SIT tools of inversion and neutralization, when applied to the reader example, could mean this:

- Inversion: The busier the customer becomes with tasks at home, the more time the customer has to read.

- Neutralization: When the customer becomes busier with tasks at home, it has no effect on the time the customer has to read.

Let’s think about inversion specifically. Generate an idea that supports this inverted relationship: “The busier the customer becomes with tasks at home, the more time the customer has to read.” Could you apply an SIT thinking tool to create this idea?

Breaking a chain of UDPs through inversion or neutralization requires overcoming resistance related to cognitive fixedness. How can you eliminate the need to keep more inventory when demand uncertainty is high? How can a person have more time to read when they are busier?

The other SIT tools can help you overcome this fixedness. For example, earlier, we mentioned one possible solution to the inventory problem: just-in-time (JIT) inventory systems. By subtracting inventory and implementing a JIT production system, you could neutralize the relationship between demand uncertainty and inventory levels.

- Now let’s apply the other SIT tools to the bookseller example:

- Multiplication: What if you (the bookseller) gave customers another way to read—one they could do while cooking or running other errands? You might develop a new strategy around audiobooks, allowing customers to get a free or heavily discounted audio version of any physical book they buy. (The books you sell are multiplied, with the qualitative change that they are now audiobooks.)

- Division: What if you took free audiobook samples and combined them into a new “sample mix” that customers could listen to while doing chores? They might find it exciting to try out several books at once, when their attention span is low, and you could track which ones generate the most interest for further promotion. You could also divide books into new sections according to customer needs (such as the length of time to listen) so that customers could match them to the tasks they need to complete.

- Task unification: Could you allow customers to use their phones to quickly add books to an audiobook “wishlist” through an app? (The phone’s camera takes on the additional task of scanning the book cover to catalog which books the customer wants to read.)

All of these ideas have the potential to alter the relationship between how busy the customer is and the amount of time they have to read.

If open-ended thinking and the SIT tools did not disrupt this cause-and-effect relationship in the problem story, you could simply try another point in the chain. Each relationship in the story is an opportunity for engaging with cognitive fixedness and making a creative leap to innovative ideas.

You do not need to create a chain of UDPs to apply inversion or neutralization. These techniques are also valuable as standalone thought exercises, even outside of problem stories. Consider the strategic approaches of Google and Yahoo during the early days of internet search engines.

Yahoo’s strategy followed a traditional approach to information management. The cause-and-effect relationship was straightforward: the more information we have, the more we need to curate. This method mirrored how people had managed information for centuries—think of libraries and databases. It seemed intuitive for Yahoo to adopt this approach.

However, Google challenged this assumption with a different question: What if, the more information we have, the less we need to curate? As the internet grew, Google created a search engine that empowered users to navigate information themselves. Instead of curating, Google allowed people to personalize their search results based on their own words, location, and other factors.

We all know who won that battle. Yahoo, like AOL, struggled to compete with the customized experience Google’s search engine offered. This example illustrates that the old way of doing things isn’t always the best in new contexts, even though cognitive fixedness often leads us to assume otherwise.

Alternate Worlds

Learning Objectives:

- Explain how the Alternate Worlds tool helps to break cognitive fixedness

- Apply Alternate Worlds to a service example and evaluate advantages and disadvantages of results

Imagine that you are designing a new carpet. For inspiration, you want to think broadly, and perhaps even abstractly, about other things that perform a similar function. What else covers a surface? Reply with something that comes to mind.

There are numerous examples for this exercise. You might think of upholstery, bathroom tiles, or tiles on a roof, but you could draw inspiration from nature too: scales covering a fish, or fur covering a dog.

Following the line of thought from bathroom tiles: Why not have carpets made of smaller pieces instead of one big piece? Once installed, it might be easier to replace one piece instead of the entire carpet. Smaller pieces might also lead to new customization options.

This leads us to another open-ended technique for breaking cognitive fixedness, inspired by the LUMA Institute’s “Alternative Worlds.”

- Alternate Worlds is a tool to identify and use perspectives from different industries, organizations, or disciplines to generate fresh ideas about a problem.

Considering alternate worlds requires empathy. Not everyone can easily put themselves in the place or mindset of someone in a different career, or in a whole new framework. It takes time and practice.

Let’s consider another example. To treat cancer, doctors need to attack or remove the tumors that grow in the body. What alternate worlds involve attacking or destroying something?

Examples include:

- Controlled burns and demolitions

- Armies attacking a city

- Predators encircling prey

This is simply a starting point for beginning to think differently about a problem. For example, just as armies encircle a besieged city to prevent escape, could tumors be attacked from multiple directions? This is actually something that occurs in radiation treatment, with less powerful radiation sent from different points of origin meeting and providing intensity only where it is needed.

So far, we have presented basic examples of how you might use the Alternate Worlds tool in creative problem-solving. Initially, it is helpful to choose simple alternate worlds that you are somewhat familiar with. This is because, regardless of the world you choose, a person from that world will not be available to tell you what they would do or say. However, if you do have the opportunity to ask someone, please do—and then compare their response with what you thought they might say.

Starting with a world you know, even a little, can build your confidence. As you practice, you will gradually acquire more skill in applying empathy and placing yourself in the mindset of another. Over time, you can venture into alternate worlds that are further from your own, broadening your horizon for ideas.

For example, consider the contemporary circus producer Cirque Du Soleil, which we mentioned in the article on subtraction. By applying subtraction, the company removed a key component of traditional circus shows—the animals—and created something innovative. But what alternate worlds could they have explored when designing their shows?

Let’s think about other forms of entertainment. How might an opera designer stage a circus? How would a rock band design a circus? What would a pyrotechnic expert contribute to a circus design? How might a puppet show influence a circus? In Cirque Du Soleil’s focus on song and dramatic staging, you can see traces of how these alternate worlds might have been applied to create their unique experience.

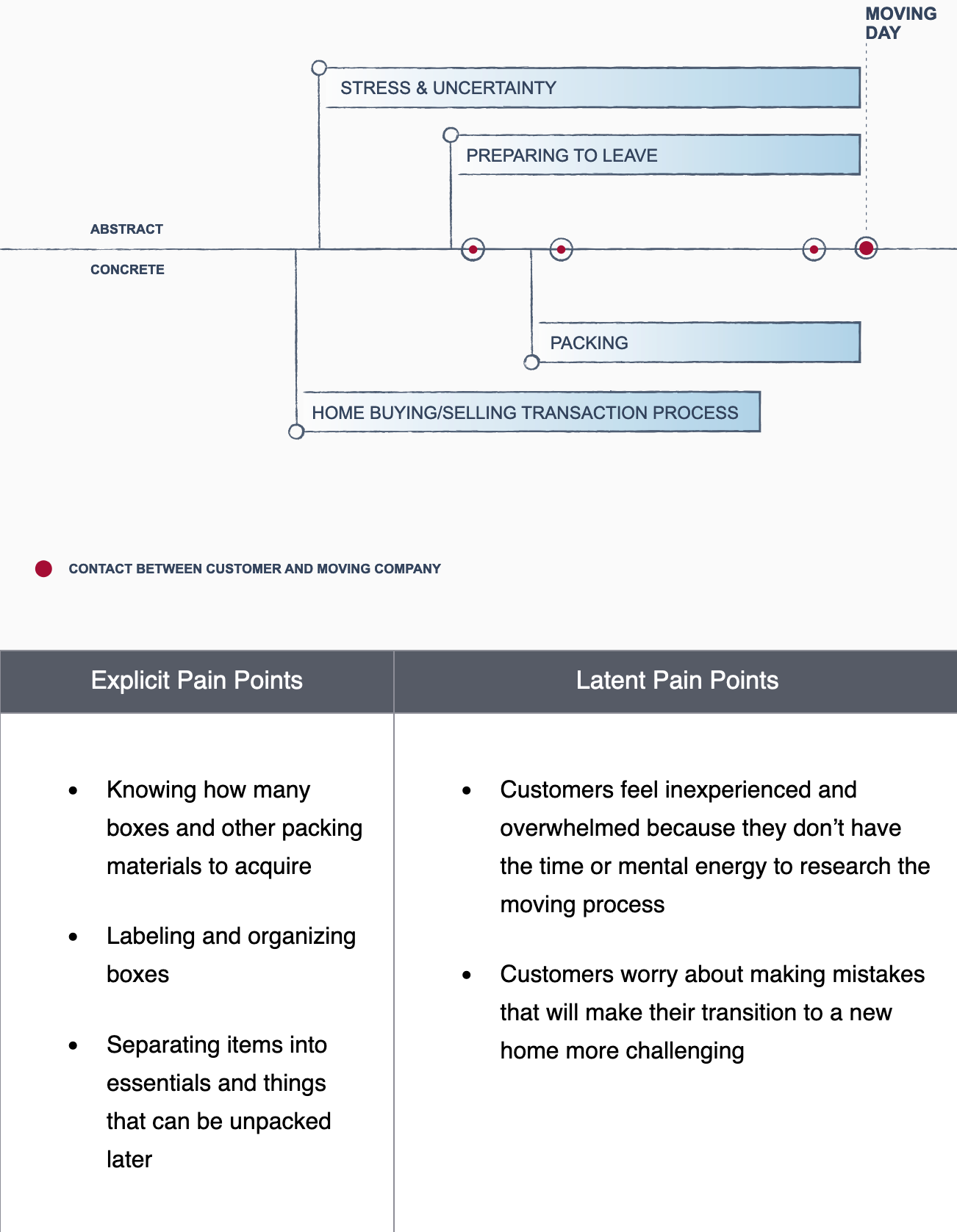

To begin applying the Alternate Worlds tool, let’s return to the journey map for customers of Gentle Giant Moving Company. Consider the following journey map and example pain points.

Remember that good problem framings help you solve the most interesting part of the problem. Given this information, what are some innovative ways to frame the problem?

Now that you recall the context around Gentle Giant and its customers, let’s review a more detailed process for applying new perspectives from alternate worlds:

- Create “how might we” questions:

- How might we help customers feel better about their efficiency and time management?

- How might we relieve customers’ anxiety in the days leading up to and following the move?

- Think of alternate worlds, starting with what is familiar:

- What other worlds are concerned with time management and transporting goods efficiently?

- What other worlds are concerned with transporting clothing? What other worlds are concerned with keeping clothes clean and ready to wear?

- In what other worlds is managing complex tasks with multiple stakeholders important and done well?

- What other worlds are concerned with time management and transporting goods efficiently?

- How do these worlds address these challenges? Think of how they solve the problem, and how these strategies might be transferred to your world.

- Repeat with other worlds.

The following are some alternate worlds that deal with time management and maximizing space and efficiency:

- Administrative assistance

- Project management

- Food transportation

- Garbage and recycling

- Dry cleaning

What would someone from these alternate worlds do to help moving customers? What advice would they offer to a moving company? Come up with two ideas, and evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of each.

There are many possible responses to this activity, but let's explore real-life examples in the context of alternate worlds for efficient packing and relieving worries about clothing transportation.

It can be challenging to come up with alternate perspectives on everyday items. Let’s revisit the initial task by thinking about alternate worlds where people routinely transport goods in ways that maximize space and efficiency.

Moving, for example, is exhausting, and dealing with boxes before and after the move is a hassle. What do waste disposal companies do to make containers more useful and efficient? They design containers to be durable and stackable. Think of how recycling bins stack together when empty.

What if a moving company could rent durable, stackable boxes? Customers wouldn’t have to worry about taping boxes together or breaking them down afterward. Additionally, because the containers are sturdy and reusable, the moving company could emphasize the reduction in cardboard waste. While there are challenges to implementing such an idea, U-Haul introduced this concept in 2017 with its Ready-To-Go Box.

Now, consider another alternate world. How do dry cleaners and people in the fashion industry hang and transport clothing? These businesses deliver clothes ready-to-wear by keeping them on hangers, even during transport. What insights can you draw from this? For instance, you might design a cardboard box with an integrated rack for hangers. This would allow customers to transport wrinkle-free clothing that’s ready-to-wear upon arrival. U-Haul also introduced a similar product called Wardrobe Boxes.

These are just two innovative ideas inspired by alternate worlds. And we’re only talking about boxes here! Many might initially think, “How can you innovate on a box?” Just as some might have believed innovating on a mop was impossible. This demonstrates the value of the tools, helping you push beyond assumptions and overcome cognitive fixedness.

An excellent tool for applying Alternate Worlds is the LUMA Institute’s Round Robin discussion. The Round Robin is a group-authorship activity that is useful in many collaborative situations.

The Round Robin has two strengths: It engages multiple team members in developing an idea, and it allows a team to consider multiple alternate worlds at once.

This is how to use it:

- Each team member selects a different alternate world. They describe the results on a piece of paper.

- Team members then pass the sheet of paper to someone else, who reads and critiques their idea. When you receive someone else’s idea, ask yourself:

- What won’t work? What is weak about this idea? What issues or problems come to mind? Be critical but constructive, and record your thoughts on the same piece of paper.

- Team members pass the sheet of paper to a third person. This person reads the original idea and the critique. The idea is now theirs—the potential, problems, and all.

- How could these issues be addressed? Apply the SIT thinking tools, Function Follows Form, or any other structured technique to follow through with the idea.

- Come together as a group and share the results.

Note: Although this activity is traditionally done in person, it could easily be recreated online using collaborative tools.

This process is beneficial for many reasons, but mainly because the person with the original idea does not become stuck in that alternate world. An outside perspective is applied at each step of the process.

Opportunities in 2 by 2 Frameworks

Learning Objectives:

- Identify the different types of tensions that a design team might encounter

- Explain 2 by 2 frameworks and apply one to a design problem

Many business problems can be interpreted as a clash of tensions. For example, the tension of cost vs need or the tension of constraints vs freedom.

Every innovation—even innovating on processes and strategy to increase the focus on design thinking—involves navigating tensions that are created by opposing forces. When encountered in a complicated problem, tension can seem difficult to navigate. Examples include:

- Now vs later

- Alone vs together

- Emotional vs logical

- Perfection vs good enough

Once you have identified these tensions, how might you use them to encourage ideation? To answer that question, let’s return to the mopping example and build a 2 by 2 framework.

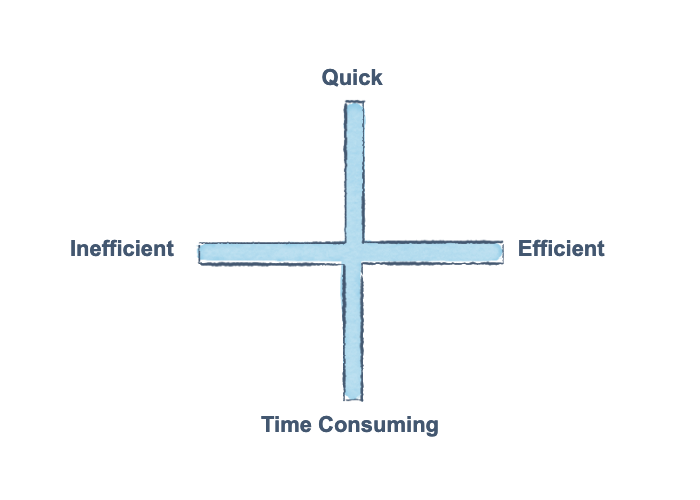

- Created by the Stanford d.school, 2 by 2 frameworks are a tool for exploring and negotiating tensions.

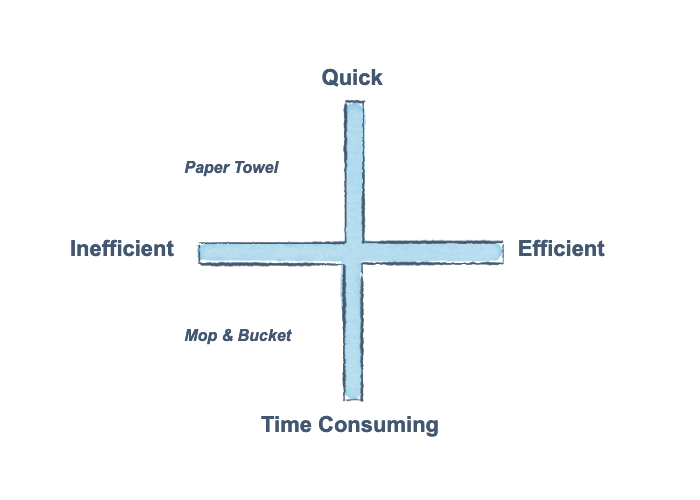

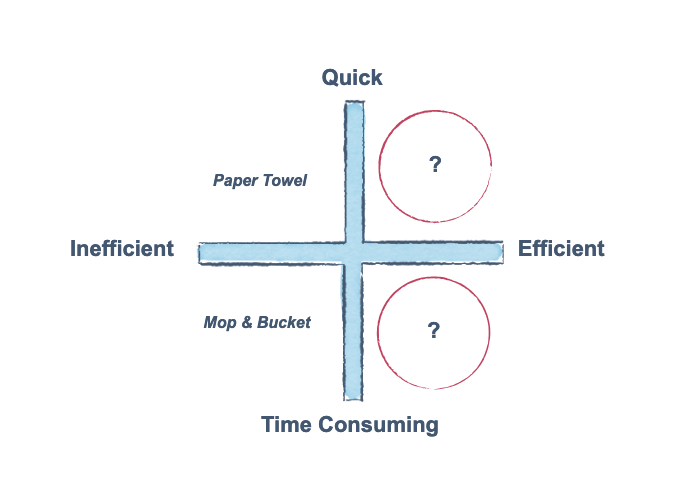

The following are some tensions in the mopping case: inefficient versus efficient (how thoroughly the product cleans), and quick versus time-consuming (how quickly the product cleans). By plotting these tensions on x and y axes, we create four quadrants.

For the purpose of cleaning floors, where would you place the mop in this framework? And what about paper towels?

In this case, the traditional mop and bucket fit in the lower-left quadrant: Research revealed that it is inefficient and takes time. Products like paper towels would fit in the upper left because they are quicker but also inefficient in cleaning an entire floor.

What about the unfilled quadrants: quick and efficient, and efficient and takes time? What products and services might fit in these quadrants, and how might we name these quadrants to categorize the solutions that would fit there?

According to authors Alex Lowy and Phil Hood in The Power of the 2x2 Matrix: Using 2x2 Thinking to Solve Business Problems and Make Better Decisions, quadrants make creative thinking more efficient in these ways:

- We let tension lead us to important questions. In the 2 by 2 framework, conflicting goals turn into markers that create focus.

- We develop a set of plausible options by considering conflicting needs.

- The four areas we identify will be rich in explanatory and provocative power.

In addition to mapping your existing products and services, you can consider other questions:

- Where do competitors fit?

- Where do you have a competitive advantage?

After analyzing the situation in this context, you can use other tools, like brainstorming or the SIT thinking tools, to generate ideas that fulfill specific strategic objectives.

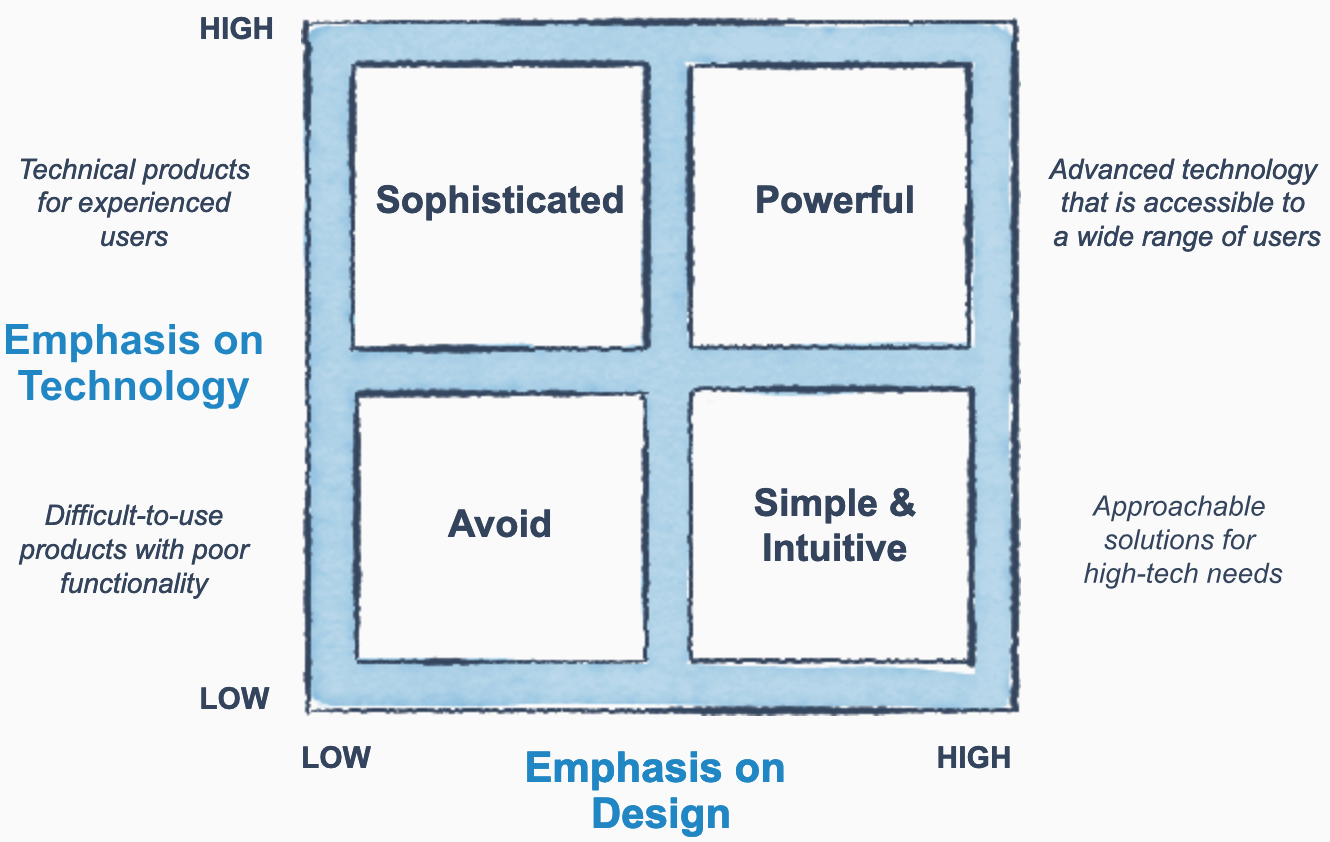

At IBM, when they were introducing design thinking, one of the many tensions they have identified was: technology versus design.

One axis will be “low-to-high emphasis on technology,” and the other will be “low-to-high emphasis on design.”

In which quadrant do you think IBM’s strategy was located in this framework before the adoption of design thinking? And which quadrants do you think they were targeting with the new design program?

IBM’s earlier strategic emphasis on technology and IT personnel put its efforts in the upper-left quadrant: sophisticated solutions for experts. What about simple and intuitive products for all users? Or powerful offerings that remained user-friendly?

The following are some examples of where this thinking led them.

- Simple & Intuitive quadrant: In 2015, IBM’s Digital Strategies and Interactive Experience (iX) group applied design thinking to help the financial services organization State Street Bank.

- State Street’s IT personnel believed they needed a cloud-based solution for a new trading platform. However, the traders themselves valued system uptime, availability, and resiliency more than automatic cloud updates of data.

- To bring the cross-functional teams into alignment, IBM’s iX group suggested a simple solution: Create a custom software application instead of a cloud solution.

- IT personnel were skeptical, but they knew a cloud application might crash the traders’ CPUs. Ultimately, they agreed to the custom software solution. The result was a reliable program that allowed traders to build intuitive custom interfaces for their needs, and IT personnel could focus on pushing data updates to the software.

- Powerful quadrant: In 2016, IBM launched Data Science Experience, which eventually became IBM Watson Studio. The program provides a friendly interface for complex data and analytics tasks using artificial intelligence. Despite its complexity and powerful customization, IBM Watson Studio is an approachable solution for data scientists.

The State Street Bank case is a great example of how IBM’s new approach balanced design and technology: The bank’s IT team wanted the most advanced cloud solution possible, but research proved it wasn’t necessarily the right solution for everyone involved.

By analyzing tensions in a 2 by 2 framework, identifying and researching opportunities, and then applying additional ideation tools like attribute dependency (price and resource usage), IBM also did scaffold a path toward innovative ideas that can be combined with others into a new concept or strategy - IBM Z mainframes applied to all aspects of the concept—including pricing.

How might IBM’s tailor-fit pricing for mainframes be an example of SIT’s attribute dependency?

In the original IBM pricing scheme, there was no relationship between the price paid for the mainframe service and what customers needed from it. In the new structure, the price a customer pays for a cloud solution depends on workload volatility, resource usage, and other factors—customers pick a plan based on their needs. As a result, IBM created a dependency between usage and price.

The 2 by 2 framework illustrates how the tension between design and technology permeated the IBM case, not just in specific disagreements between designers and engineers but also in IBM’s overall strategy. Before the introduction of design thinking at IBM, this tension was skewed in favor of technology. Product development teams prioritized sophisticated solutions for expert users, while user feedback and design considerations were secondary.

When this tension was balanced, however, new opportunities emerged. For example, the framework highlighted “simple but intuitive” products in the low-tech, high-design quadrant and advanced yet approachable technologies in the “powerful” quadrant. This demonstrates the strength of the 2 by 2 framework—it helps analyze complex situations as a set of competing interests. Rather than seeking a single correct solution, the aim is to gain understanding, perspective, and insight.

Interestingly, amplifying the tension between design and technology increased opportunities for IBM. It’s important not to let one side dominate, as both hold value. Thesis and antithesis lead to synthesis. The framework also compels us to consider options that might otherwise be dismissed, including those with high benefits despite high costs.

This underscores why generating ideas before evaluating them is crucial. Teams with high levels of trust and psychological safety can navigate this process more effectively, often uncovering surprising and innovative ideas.

The tension in the IBM case was organizational, but you can also plot strategic and even individual tensions in a 2 by 2 framework. The following are some examples:

- Strategic tensions = Product vs. market, cost vs. benefit

- Organizational tension = Internal vs. external, change vs. stability, speed vs. scale and scope

- Individual tension = knowns vs. unknowns, urgent vs. important, meaningful work vs. ability to succeed

Remember, the goal of 2 by 2 frameworks is not to find a single solution. Instead, it is an open-ended exercise designed to explore opposing tensions and provide guidance for brainstorming or applying the structured tools from Ideation. As different tensions surrounding a design problem are resolved, new ones will naturally emerge.

In the IBM case, the focus on design versus technology was just one tension. Other tensions included centralization versus distribution—how do you ensure consistency while empowering individuals to innovate?—and empathy versus data-driven insights—how do you reconcile these when working with AI technology? Plotting these tensions in a 2 by 2 framework and examining the quadrants can provide clarity and focus for ideation while uncovering opportunities.

It is important to note that tensions evolve over time, reflecting a continually changing set of dynamics. Learning often requires unlearning, and progress in one area frequently demands sacrifices in another. A win in one dimension can come with a loss in another. This fluidity underscores the importance of remaining open to new possibilities and regularly re-evaluating the tensions you map in a 2 by 2 framework.

A good starting point is to focus on fundamental tensions that are almost universal, such as costs versus benefits, internal versus external considerations, and change versus stability. The framework can even be applied to more abstract tensions, such as the conflict between head and heart—what is logical versus what is right.

Rather than limiting progress, these tensions should be used to expand the scope of ideation and uncover new possibilities. Let them guide your exploration rather than serve as obstacles.

Brainstorming

Learning Objectives:

- Describe the process of brainstorming and when to use it

- Practice preparing for a brainstorming session

You just practiced with frameworks for ideation like alternate worlds and 2 by 2 frameworks. But what if you want complete freedom in generating ideas?

Merriam-Webster's dictionary definition of brainstorming is “a group problem-solving technique that involves the spontaneous contribution of ideas from all members of the group.” The key words are spontaneous and group—these lead to our common understanding of brainstorming, which is discussing a problem together and following spontaneous ideas wherever they lead.

In the modern workplace, brainstorming is often done with sticky notes or a whiteboard (or the digital equivalents), and the results are dependent on the dynamics of the group and the problem being discussed. Some find it productive; others do not.

What are the downsides of unstructured brainstorming, in your opinion? Have you found it useful in the past?

Brainstorming allows you to think about pain points and unmet user needs without regard to any particular framework. Once you have invested deeply in understanding a problem and gaining insights, new approaches and ideas will start coming to mind.

As with the SIT tools and the principle of Function Follows Form, the goal is to generate as many ideas as possible (by whatever means) and then to consider the benefits and challenges (in that order).

However, while brainstorming can result in interestingly radical ideas, it can also result in ideas that may be difficult to implement, and it can easily lead to differences of opinion. Since there is no structure or process that everyone shares, each person may think they are right. This can lead to unproductive interactions.

There are times when brainstorming is the most suitable approach for tackling an innovation problem. Brainstorming allows you to freely imagine ideas without structural constraints. After investing deeply in understanding a problem and gaining insights, new approaches and ideas will naturally start to emerge.

Like with the SIT framework, the goal of brainstorming is to generate as many ideas as possible before assessing their desirability, feasibility, and viability. While brainstorming can lead to intriguingly radical ideas, it also has the potential to produce ideas that are too far-fetched or difficult to implement. Additionally, the lack of structure can result in differing opinions, as each participant may feel their ideas are correct, leading to unproductive interactions.

For this reason, structured brainstorming is often more effective. It aligns with my earlier advice to work individually first and then refine ideas as a group. Here’s how it works:

1. Start by brainstorming individually. Each participant should generate ideas on their own.

2. Come together to share ideas. Allow everyone to present their contributions without immediate judgment.

3. Evaluate and discuss as a team. Once all ideas are shared, evaluate them collectively, focusing on one conversation at a time.

This approach ensures that everyone has the opportunity to contribute and participate meaningfully in the discussion. Although brainstorming doesn’t rely on specific tools, you can use any of the ideation tools introduced here to expand and refine the results effectively.

These are the guidelines that the design firm IDEO recommends for brainstorming productively:

- Encourage wild ideas: Brainstorming provides the most freedom for creative thinking. Let the group decide if an idea isn’t worth pursuing.

- Go for quantity: The more you have to discuss, the easier it will be to maintain momentum.

- Be visual: Try sketching ideas as well as writing them out to activate different parts of the brain.

- Be respectful to others.

- Defer judgment: Keep the focus on the idea, not the person, and be genuinely open-minded.

- Build on the ideas of others.

- Focus on the task.

- Have only one conversation at a time. A moderator should keep everyone on task.

- Stay focused and avoid distractions.

Review: Ideate - Tools and Frameworks for Generating Ideas

In the last couple of articles, our focus was on Tools and Frameworks for Generating Ideas in the Ideate phase of design thinking.

We explored a large number of tools and processes in the ideate phase of design thinking. As we have stressed throughout, these tools are not part of a rigid process. The goal is to find what works for the context of the problem, and then use whatever tool or process you need to begin ideating and generating solutions.

Let’s review what we covered:

Design Principles

- Design principles are the bridge between user research and ideation.

- They provide a lens for evaluating the user focus and desirability of innovation ideas.

- Design principles form the column headers of the creative matrix.

- The most useful design principles are general and allow for the broadest possible ideas (e.g., “improved focus on task”).

SIT Tools for Innovative Problem-Solving

- Task unification

- Multiplication

- Division

- Subtraction

- Attribute dependency

Open-Ended Ideation

- Creative problem-solving: problem stories, UDPs, inversion, and neutralization

- Alternate worlds

- Tensions and 2 by 2 frameworks

- Brainstorming

There are many tools and principles covered, don’t worry if you cannot remember them all right now. The goal isn’t to memorize them perfectly, but to improve your ability to apply them through practice. Over time, you will develop the skill to overcome cognitive fixedness and view innovation problems from fresh perspectives.

In the realm of design thinking and innovative problem-solving, another balance must be maintained. We’ve discussed that skipping to the ideation phase without conducting user research can lead to solutions that offer little value to users. However, an exclusive focus on user pain points can also stifle open-ended exploration.

Sometimes, it’s beneficial to use these ideation tools without considering user input. This is perfectly acceptable. In a true design-thinking process, you would eventually return to user research to refine and validate your ideas.

Innovation is about learning to break fixedness and embracing the tensions within ideas. This takes both time and practice.