The Curse of Knowledge

Implement: Communicate and Structure for Success - Overcoming Developer and User Bias

Learning Objectives:

- Describe the implementation phase of design thinking

- Explain why communication is difficult for people embedded in long-term design projects

Welcome to the final, Implement, phase of Design Thinking.

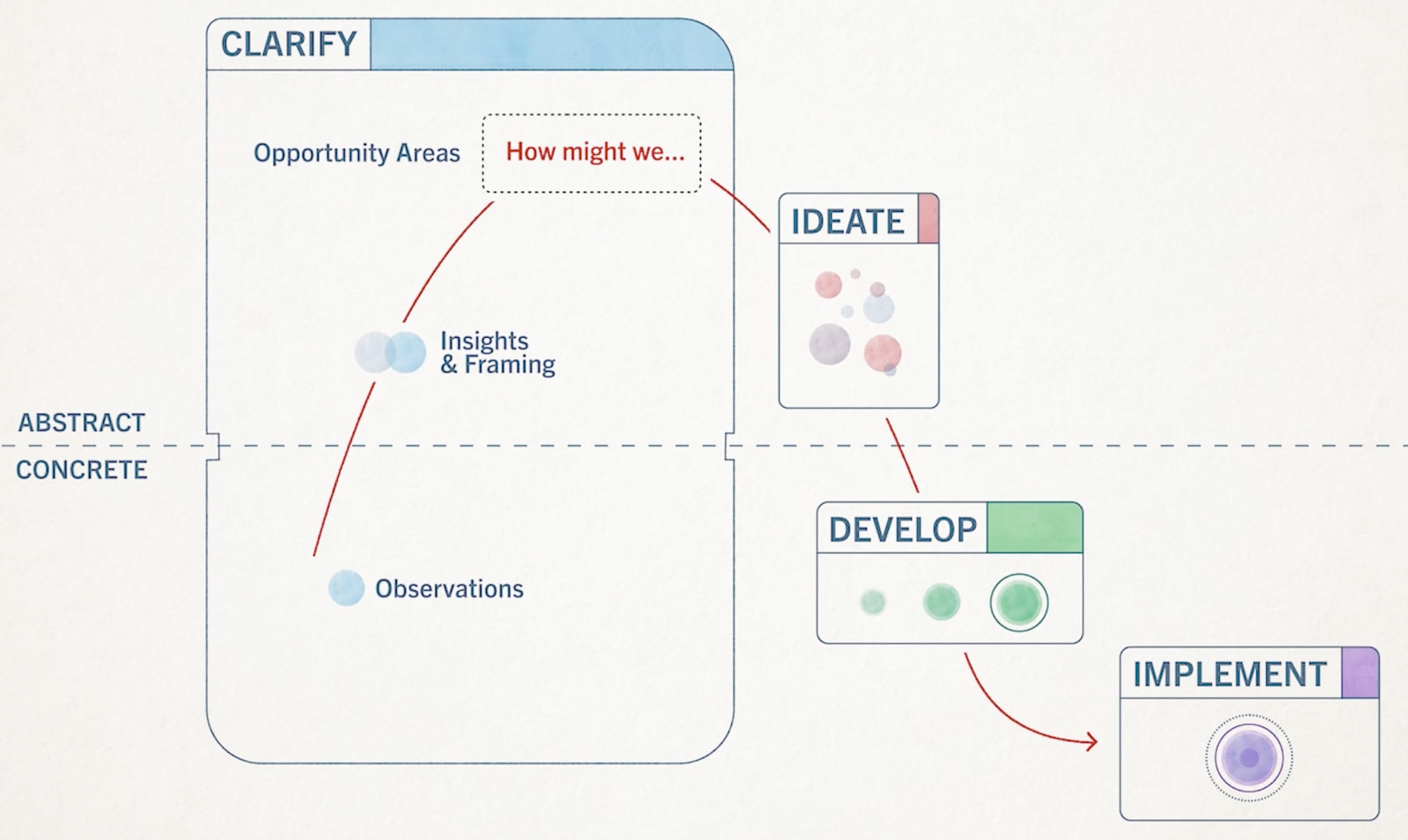

You are now familiar with the research, ideation, and development phases of design thinking. We will now focus on the last and perhaps most overlooked phase, implementation.

The fact is that many innovations fail even when they fulfill user needs, address pain points, and are demonstrably feasible and viable. The reasons for this are complex. Sometimes, bad timing or bad luck prevents a promising innovation from being successful. But another, more preventable cause is the significant gap between the developers who have been living with their innovation for months or years and the external users and stakeholders who might benefit from it but know nothing about it.

It is difficult to cross this gap to communicate the value of an innovation. But we will see you how to analyze and structure communications for an increased chance of success.

Finally, we will end the Design Thinking topic with a deeper analysis of another aspect of implementation, what it means to build a culture of innovation. This is not a hands-off process. Most businesses want to encourage and sustain innovation in the long term, but they run into familiar roadblocks.

We will explore the most common innovation inhibitors, as well as the characteristics that innovation leaders should strive to possess.

Once again, we will provide tools and frameworks for approaching this phase, including a structured way to analyze team composition.

Now, let’s explore the implement phase of design thinking!

In a 1990 psychology study at Stanford University, subjects were paired and each was given a role: either tapper or listener.

The tappers had to think of a song and communicate it to their partner. However, they could not sing or hum or recite the lyrics—they could only tap the rhythm on the table using their fingers. The listeners had to guess the name of the song just by listening to their partner’s tapping.

Before the experiment began, 50% of the tappers believed their partners would identify their song. The thing is - the song may seem obvious to the tapper, but the listener has an extremely difficult task. Let's understand the most important lessons that innovators and entrepreneurs can take away from this exercise:

DEAN DATAR: As you were doing the exercise, I think you realized that it's very hard for the listener to guess the song. It was a very simple song, so Old MacDonald Had a Farm, London Bridge Is Falling Down.

KOFI: Old MacDonald, that's the one I thought you did.

DEAN DATAR: It is very hard for the listener to appreciate what it is because for the tapper, the tapper is hearing the music playing in their head. So, if you are far away from where you were listening, the tapper thinks, it's not so hard. I said, London Bridge is falling down, falling down, falling down. London Bridge is falling down. So what's so hard about that? It's clear. But it turns out that, for the listener, it's very difficult. And, as your exercise suggested, when this experiment is done many, many times, only 2.5% of the songs are actually correctly guessed. It's that hard.

But the tappers, when they are asked how many they would get, and roughly along the lines of what you were describing, Giulia said that if you're a very good tapper, you said three out of five or four out of five, so 60% or 80%. Good listeners, simple songs, known songs, but the difference between 60-80% and 2.5% is huge.

DEAN DATAR: We refer to this as the curse of knowledge. So, when you're an innovator, you have to have that optimism that innovation is going to work, rather you'll never try something that different that has not been tried before. And, once you have that optimism that something is going to work, you're going to overestimate how much the other person knows because you've come up with something, and you say, will the world like it? Of course they're going to love it because I spent a lot of time thinking about whether they would love it or not. So why will they not love it?

But you're the tapper. As far as the listener is concerned, looking at your innovation, say, what's the big deal? What is this? Why should I be interested in what it is that you've done? It's of no great–and so a large part of when we're thinking about innovation is not just around what you have come up with, how you have prototyped it, as we have talked about, but about how do you communicate your innovation in a way that the listener is drawn into the innovation in a way by which they can begin to like it?

And, whenever you're innovating, it's not good enough to come up with a great idea that you think is great because you better think it's great as an innovator. If you don't think it's great–but it's not enough to stop there just because you think it's great. You have to pay great attention to doing it, and you have to be very aware of the tappers and listeners problem, that you're continually tapping out, this is so great, this is so great. This [MUMBLING]. I can't understand a word what you're saying, and why is it so great? It's nothing so great. And so they're only getting snippets of your innovation.

So how do you then, as an innovator, get people to do it? And someone like Steve Jobs, master as he was at innovation, he knew exactly how he was going to hook you in when the iPod comes on or the iPhone comes out. Whatever comes, it's this ability to understand what the listener is feeling and experiencing that is very important to have innovation really work.

While many teams believe they will identify 50% of the songs or more, they typically identify only 2.5%.

In a 2006 Harvard Business Review article, Stanford professor Chip Heath and business consultant Dan Heath use this experiment to highlight what they call “the curse of knowledge”. This is the idea that once we know something, it is extremely difficult to imagine not knowing it.

The experiment with tappers and listeners is easy to replicate at home with a partner or even by yourself. Simply tap the melody of a song on the surface in front of you. You will notice that it's impossible to avoid hearing the song in your head as you tap. It is very difficult to put yourself in the listener's position. And if you try this exercise with a partner, it'll be harder than you think. They may recognize the tune of the "Happy Birthday" song, but anything more complex will probably sound like an unusual rhythm.

How does this all relate to innovation? Just as tappers cannot unhear the melody as their fingers strike the table, businesses cannot un-know their deep understanding of their innovation's value. They often have trouble making clear communication about the products, services, models, and strategies that they have spent months or years developing.

In their 2006 article "The Curse of Knowledge," Chip and Dan Heath illustrate this application of the tapper and listener experiment through the example of Trader Joe's, a specialty grocery chain with unique offerings and a meticulously designed experience. They point to Trader Joe's mission statement. At the time, the mission was, "To bring our customers the best food and beverage values and the information to make informed buying decisions."

What does this communicate to you? What message do you think this mission statement is trying to convey?

- Their stores are user-friendly.

- Their stores offer good prices.

- Their stores provide helpful nutritional information.

- Their stores are transparent about their supply chain.

To the average person, this Trader Joe’s mission statement is quite vague. It’s hard to say which of these options is correct, even though shopping at Trader Joe’s is a unique experience. The organization communicates its unique strategy in other ways.

If you have ever visited a Trader Joe's store, you know that it defines value in a specific sense. Trader Joe's does not have sales, membership programs, or other incentives. They keep prices low through deals with third-party suppliers. And they rely on the brand and the store experience to sell their products.

The exotic foods, handwritten signs, outgoing employees, and focus on experimental and seasonal products all create this unique experience that delivers value. Because of this innovative model, Trader Joe's has a loyal cult following in the United States. It does not need to win anyone over.

But if this were a new innovation, the original mission statement would be an example of what Chip and Dan Heath call "CEO language." People at high levels of the organization know what value means in the context of Trader Joe's. But someone unfamiliar with the store would be puzzled. To the average consumer, the phrase, "to bring our customers the best food and beverage values and the information to make informed buying decisions" sounds like something any grocery store does.

Communicating an innovation's value in CEO language is equivalent to tapping the melody of a song and expecting your listener to guess the tune. At this point in the design thinking process, you'll be so close to your innovation that you may have trouble articulating its value in the right way to promote adoption and behavior change.

To make this process easier, we will review some structured ways of analyzing audiences and communications.

By the time you reach the implementation phase, you will know your final innovation extremely well. To avoid the “curse of knowledge” and communicate the value of your innovation effectively, you must maintain a human-centered approach by researching stakeholders and applying innovation tools to your communication and implementation strategies.

In this final phase, we will focus on these tools and strategies by examining, among others, the case of Royal Philips, commonly known as Philips.

Originally, a lighting company, Philips transformed in the 2010s from a highly diversified industrial holding company with falling revenues and increasing competition to an international leader in the healthcare industry.

CEO Frans van Houten came to his position in 2011 facing the challenges of a decade of underperformance. Foremost was the question of whether Philips should divest the company’s foundational business group, Philips Lighting, and shift to innovative healthcare solutions. To do so, Philips would need to develop a sustainable culture of innovation.

In the following video transcript, Frans van Houten shares more on the thought process behind this decision.

I'm Frans van Houten. I'm the CEO of Philips since 2011. I had the privilege of leading the adventure of reinventing Philips, which is a company of 130 years old, and to make it relevant for the future. So we had to do a complete portfolio reset to say, where actually are we differentiating? Where can we, let's say, apply our innovation strengths and solve the unmet needs of the world?

Because in a way, innovation is about discovering unmet needs. And then doing a better job to distinguish yourself versus your competitors. And to do that with longevity. In other words, a company of our size, it's not about doing one product very well because you will never get there, you will not beat that size.

So this analysis resulted in, over the next three years, of the first three years of being CEO, that we exited television, audio video, LEDs, lighting, as being all areas where commoditization was far advanced and the race to be in front with an innovative concept would be hard. Whereas, we chose health as representing a very large market.

And of course, we are all aware of growing population, aging population, more lifestyle diseases, so the health care market is growing. But also a market where society grapples with the cost. We need to reinvent how we look at health. And technology can really make a difference. And with technology, I mean, both software systems, services, the whole shebang.

And we had a good starting position in health care, although, at that time, it only represented about 20%-30% of the company. So we chose to divest of everything else and become focused on health. And within that, we developed a strategy to innovate in a meaningful manner.

If you look and analyze health care, it's, unfortunately, still today, very volume oriented, episodic, triggered by an incident. And it is not yet really end to end. And many health care practitioners work very hard, but frankly speaking, they are operating in silos.

And our vision was to create an end-to-end redefinition of health care, platform-based, whereby data would inform decisions at every point of the journey so that you can optimize effort and maximize outcome. We adopted what is called in health care the quadruple aim of care: driving better outcomes, higher productivity, and a better patient and staff experience.

So if you think about that, you go to tear down all the barriers in health care, between primary care, secondary care, tertiary care, between practitioner A, B, and C. All right. And think of it as, actually, a lean process. Think of it as a design cycle, right? And where you actually need to think about designing an experience that leads to a better outcome.

And if you use value stream mapping, you will find out what works and where is the waste. And if you then take the user perspective into account, whether it's a health care professional or the patient, and you look at the end goal, which is to help as fast as possible to bring somebody back to a decent level of health, you start organizing your processes differently.

Now, this is the context, and in that context we want to innovate.

The change to Philips’s strategy that Frans van Houten wanted to implement would require researching the day-to-day operations of their healthcare clients and investigating the needs of stakeholders across the spectrum of care. Crafting effective communications, and creating the right environment for innovation to thrive, would be key to making this transformation work.