The Elephant and Rider Framework

Implement: Communicate and Structure for Success - Strategies for Communicating Value

Learning Objectives:

- Describe the different perspectives on user behavior in the Elephant and Rider framework

- Identify opportunities to reframe implementation strategy in response to a challenge

The Elephant and Rider framework by psychologist Jonathan Haidt is another creative way to think about the motivation and ability required to promote behavior change and the adoption of an innovation.

In the Elephant and Rider framework:

- The rider is rational. They know the path and provide direction.

- The elephant is the power for the journey. It is instinctual and emotional.

These two characters are a metaphor representing the two different sides of the user. Without thinking, we might structure communications to appeal to one or the other: the rational or the emotional side. However, it is better to balance both.

In the metaphor, the elephant and the rider must work together to move in a specific direction. The rider may know where to go, but if the elephant does not want to move in that direction, the rider cannot force it.

Likewise, if the elephant is drawn in a certain direction, but the rider does not understand why or thinks it’s a bad idea, the elephant may be diverted later.

When you are crafting a communication strategy for your innovation, consider how you might convince the elephant and rider to work together. This involves helping the user understand your innovation in context, and giving them the motivation to adopt it.

Even when users understand the benefits of your innovation, they still may lack the motivation to adopt it. When this occurs, you focus on building personal connections. Christi Zuber explains in the following video transcript how her team led nurses through a complicated process innovation.

We were changing around shift change for nurses, which is shift change in a hospital setting is the transfer of information. Historically, it's been between nurses. And to kind of make a long story short, we wanted to change it to where it involved also the patients and their family members at the bedside.

That seems like a very simple shift. It was actually quite a substantial shift to do that. We changed around the dynamics, who's a part of what, how things are discussed, how they're captured, the technologies that are used, et cetera. And so in doing that, we realized that there were a lot of contextual things that would need to change, that interruptions during shift change of calls that would come into the unit, other requests that would come in, couldn't happen because the nurses would be in the patient's room.

So a lot of external things needed to change. We learned that it was very uncomfortable for nurses to do this for a period of time. It might just be a shift, it might be a week, it might be a couple weeks, but there was both a learning curve and a comfort curve that went into people doing this differently.

And what we learned is, if they get their own time to get some insights and observe for themselves and don't just have to take our word for it, it actually begins to get them more open and interested in the change.

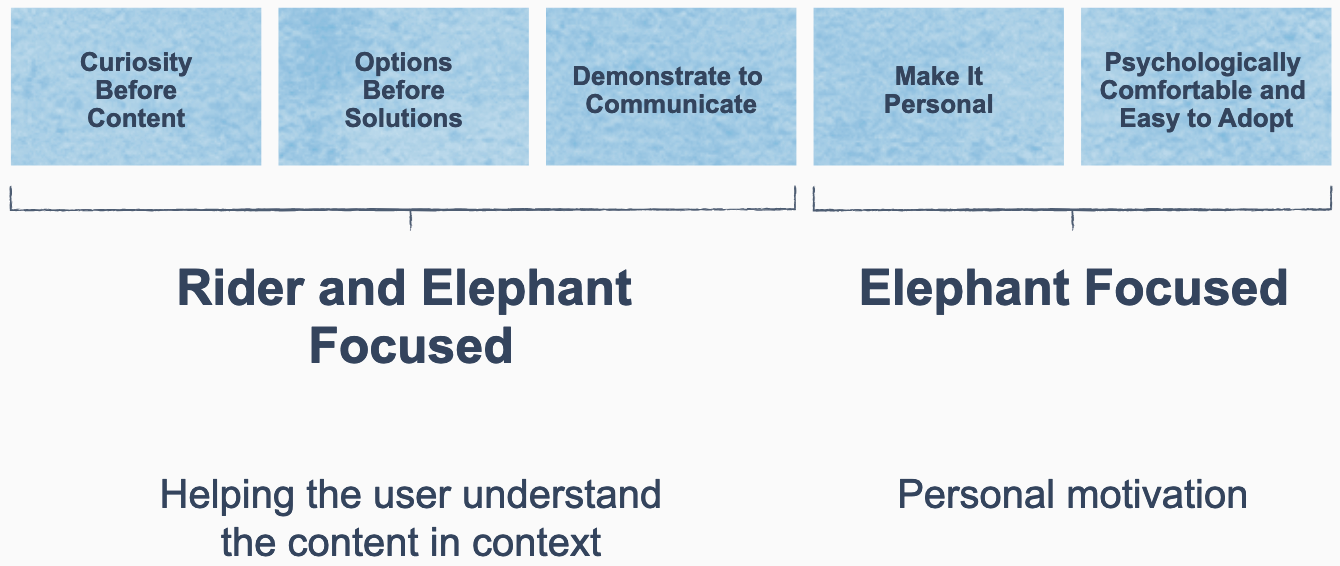

One useful approach to “convincing the elephant to move” is focusing on the principles of communication that help people understand how an innovation will fit in their life or routine:

- Demonstrate to communicate

- Make it personal

- Psychologically comfortable and easy to use

In Christi Zuber’s preceding example, the innovation would disrupt nurses’ processes and routines, and thus how they experienced the flow of work. The status-quo bias would be strong. What might you do to emphasize simplicity or compatibility—to make the “elephant” feel motivation to move?

CHRISTI ZUBER: We would say, OK, so for these first few shift times, all we want you to do is to track the number of patient and off-unit phone calls that come in during the shift. Because we've heard you say those are interruptions, and you're worried that those things will take you away from the bedside. So let's track how many of those come in.

So then it gave them their own insights about how busy was their unit, how many of these things would come in. And then we'd say, OK, so now based on that, what ideas might you have to address it? They'd come up with some of their own ideas. So again, getting into their own cycle of ideating.

What we learned over time is there's a handful of things that they would all almost come up with. But giving them the opportunity to do that. And then they'd try some of their own small tests. We're going to have it so that our charge nurse is set up to address calls so that the staff nurses can be at the bedside and not worry about missing calls or what have you, that we can focus on the patient. Great, let's do that.

It was a behavior change for the staff nurses. And you can't underestimate what that means. Just because you've told them this is how successful the pilot's been, this is what's going to happen, now you guys go forth and do it. People don't change in that way.

So I think when we're talking about scale and spread and implementation, and again, this is an example of a service design, but I think that bringing people into it in that way is really important. Now, it doesn't mean it's going to take that whole amount of time. This was something that we might do over let's say a week or two, and then they're up and running. But I do think that that's really important for implementation and scale is being transparent.

By guiding nurses to identify their own needs and pain points, Christi Zuber and her team convinced them to take ownership of the new process. “Demonstrate to communicate,” “make it personal,” and “psychologically comfortable” are all reflected in this strategy.

Remember this about the elephant and rider framework. If the elephant and rider disagree on direction, the rider will always lose. The elephant is more powerful and cannot be pushed around. This metaphor is applicable to innovation in numerous ways. You may be convinced that your innovation is superior to what is available in the marketplace, but you cannot expect solely rational appeals to always work in convincing users to adopt it. Users must want intuitively or emotionally to adopt it as well.

For comparison, think back to the Ideate phase and the complementary forces of ability and motivation when guiding behavior change. The Silent Middle in the Insigne health case were the patients at risk of chronic disease later in life, and yet, previous attempts to encourage healthier lifestyle choices had failed. Doctors and nurses made logical and perhaps even emotional appeals, but for a variety of reasons, the changes were too overwhelming to think about.

You can clear the path, and you can even convince users that it is the correct path, but if they do not want to move, they will not. Even in Steve Jobs's presentation introducing the iPod to the world, he was careful to balance rational appeals with emotional ones about our shared love for music and our shared frustration in not having it all available to us when we want it.

This is why user research and the tools for behavior change analysis can be useful again, even in this late phase of design thinking. Understanding pain points and user's current levels of ability and motivation will help you craft balanced messaging that addresses both the rational and emotional sides as they consider whether or not to abandon the status quo.

The lack of acceptance of seat belts was largely an elephant problem:

- Many drivers did not appreciate the full benefits of seat belts, even though those benefits could be explained rationally. For example, drivers assumed they were in control of their driving, and therefore in control of whether they would get into an accident. In reality, the drivers were not as safe as they believed.

- Drivers did not find the innovation compatible, either with their own perception of their driving ability or with their beliefs about government safety regulations.

Either of these considerations might lead to new communication strategies—such as passing child safety laws—which is the goal of the framework.

In his comments on overcoming skepticism of design thinking at IBM, General Manager of Design Phil Gilbert notes that building motivation often begins with creating buy-in with small, open-minded groups. The success stories of these groups may appeal to both the emotional and rational needs of skeptics.