The Ideation Process - Getting Started With SIT

Ideate - Tools and Frameworks for Generating Ideas

We started exploring the ideate phase of Design Thinking and introduced Design Principles to establish focus, SIT and Creative Matrix. In this article, we will dive deeper into SIT.

Ideation and Cognitive Fixedness

We will:

- Define the scope of the ideate phase of design thinking

- Explain cognitive fixedness and identify the different types

Imagine that an organization wanted to innovate on the design of bicycle helmets. The team working on the project developed the following design principles:

- Strong to absorb impact

- Fashionable/attractive

- Easy to store

Do you think these design principles would lead to a variety of innovative solutions? Explain why or why not.

Remember that design principles must be general enough to allow for creativity and exploration. This often means checking your assumptions about what a solution might be.

In the case of redesigning a bicycle helmet, a design principle like “strong to absorb impact” might suggest that the solution will be hard or large, like a traditional helmet.

In reality, two Swedish designers launched an inflatable bicycle helmet, the Hövding, in 2011. The helmet fit in a pouch that the rider wore around their neck. It inflated, much like an airbag, when sensors in the pouch detected that the rider was in an accident.

The creators of Hövding, Anna Haupt and Terese Alstin, marketed it as a high-fashion item, which is another break from what we assume safety equipment should be.

Innovative problem-solving is difficult because our brains are wired to approach problems in traditional ways. As we explore the SIT methodology and other approaches to ideation, you will learn how to overcome the different types of cognitive fixedness that can prevent people from generating original and insightful ideas.

Cognitive fixedness is a state of mind in which we consciously or unconsciously assume that there is only one interpretation or approach to a situation. For example, the idea that a cup can only be used to drink liquids, and likewise, that you cannot drink from anything but a cup.

Is cognitive fixedness unbreakable? Obviously not. Or else no one would ever generate creative, new ideas. But cognitive fixedness is difficult to overcome. And cognitive fixedness is usually a benefit. It functions like a mental shortcut, allowing our brains to rely on past experiences to solve problems. We don't want to stop and think about what we should use to drink water every time we are thirsty, so we don't even consider alternatives. And that is fine in day to day life.

Cognitive fixedness increases the efficiency of our thinking, but it can also prevent us from imagining new possibilities, which is an important part of the ideate phase of design thinking.

We will examine three different types of cognitive fixedness and how the tools in the creative matrix can help you overcome them.

Functional fixedness limits us to considering only the traditional use of a product or service. For example, you may think of a coffee filter only as a filter when it could also be used as a small disposable bowl or as a soft layer when packing dishes.

Structural fixedness limits us to considering objects and services as whole things that cannot be divided or rearranged. For example, think of a television. For years, TV sets were large boxes with screens, speakers, knobs, controls, and various electrical components. Could a TV set possibly be divided? We know that it can because these attributes were separated over time. For example, the controls were taken off and placed on a remote.

Relational fixedness limits how we interpret the relationship between attributes of a product or service. Specifically, we understand them as fixed and unchanging. For example, a business might assume customers should pay the same for packages, no matter when they're delivered because that is how things have always been done. However, there is no fixed relationship between the shipping attributes price and time of delivery. A customer could pay less if a package is delivered later or more if it's delivered sooner.

These are a few quick examples of cognitive fixedness. In each case, we start with an existing product, service, or model, and then we explored how we might use it differently or change it. As you practice with the SIT thinking tools, you will become better at identifying these mental blocks and overcoming them.

The following is a brief review of the types of cognitive fixedness presented in the video.

- Functional Fixedness - Considering only the traditional use of a product or service

- Structural Fixedness - Considering objects and services as whole things that cannot be divided or rearranged

- Relational Fixedness - Interpreting the relationship between the attributes of a product or service as fixed and unchanging

For each of the following scenarios, identify which type of cognitive fixedness best fits the statement - functional, structural, or relational:

- The freezer is the top compartment of a refrigerator - Structural Fixedness (assumes that the compartments of the refrigerator cannot be rearranged)

- Customers order drinks when they are in the café - Relational Fixedness (assumes that the relationship between the act of ordering and the time or location of ordering is fixed)

- You use a key to open a door - Functional Fixedness (overlooks other uses for a key, such as using it as a hook)

- The mug’s temperature changes when it is filled with hot coffee - Relational Fixedness (assumes that the relationship between the temperature of the mug and the temperature of its contents is fixed)

As you attempt to break cognitive fixedness, you can approach the problem from two complementary perspectives:

- Voice of the customer: When we generate ideas in response to user pain points, we are starting with the voice of the customer. For example, we might ask, “What new ideas do you have for making the cleaning process take less time?” This is the powerful approach traditionally associated with design thinking.

- Voice of the product: Another approach to ideation starts with cataloging and then experimenting with the existing resources around you. We might ask, “What would happen if we subtracted something essential from one of our current cleaning products?”

- By listening to the voice of the product, you create new forms that might fulfill user needs in interesting ways.

The SIT thinking tools balance both approaches, but they often begin with the voice of the product. Instead of trying to think of new products and services from scratch, you change what already exists and evaluate how novel and useful the new form might be.

Yoni Stern of SIT elaborates on these two approaches and how they complement each other:

At SIT, we believe that innovation needs to start from a mapping of the current situation. The current situation is usually a compilation of what's happening with the users or the market at that time and what exists as your resource base as an organization, as a company, that's looking to innovate to provide more value for your users or to, perhaps, even open up a new market. And therefore, what we look is always to listen to the voice of the customer, of course. That's very important. If we don't understand who our customer base is or who we're providing value for, you're not going to get a valuable innovation at the end. However, what we find is that many organizations and many approaches ignore the second half of the entire environment. And that's the environment of your resources of the product, of the system itself that you're looking to innovate the situation of the use of that system, and all those elements that aren't related specifically to the market or the user and what are the resources that are there in the existing situation in order to figure out how you can best leverage them, how you can think differently about them, and how you can utilize them in order to meet those needs that you uncover or even uncover new, latent needs that the customer might not have even been aware of and know that they wanted or needed or found any benefit of. So if you have that dual system, where you're scanning both the voice of the customer and listening to what they're looking for, whether it's through empathy or ethnography or others, more standard research methods, and you supplement it and complement it with listening to the voice of the product or listening to the voice of the system, a deep understanding of what you have as a resource base, then you have a much fuller picture and a much greater wealth of resources in which to use in order to create true innovations that sometimes even surprise the user and surprise the market.

Task Unification and The Closed World

We are going to:

- Define task unification

- Apply task unification to different design problems and justify the desirability of a solution

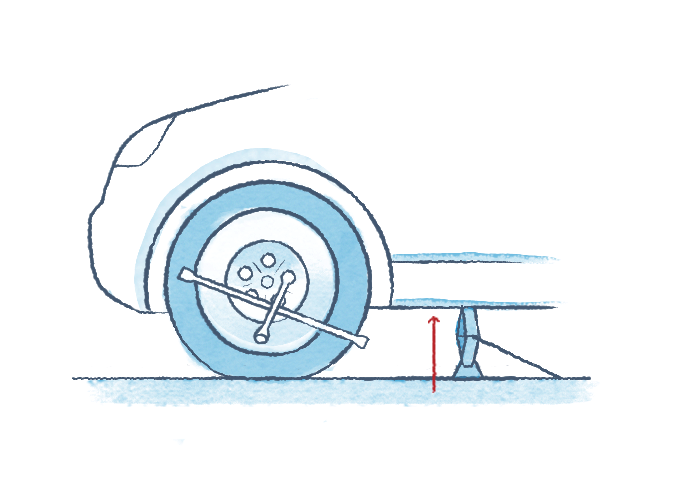

Imagine that you are driving to a job interview and you get a flat tire. You rush to change the tire, lifting the car up with a jack and then using a cross wrench to unscrew the nuts on the tire.

Suppose the first four nuts come off easily, but the fifth is rusted and won’t move. What would you do in this situation to get to the job interview?

There are a number of creative solutions to this dilemma. You might break the rusted bolt using a tool in the trunk, or you might apply a lubricant to it, such as oil from the engine or a cream you may be carrying with you.

Another innovative solution uses only what exists in the image, and it gets both you and the car to the interview with little time and effort: You lower the jack and use it to apply extra torque to the wrench. This loosens the bolt so that you can change the tire as normal.

Once you know this solution, it seems very simple. But under pressure and worrying about the interview, many people struggle and do not think about repurposing the jack. This is because the jack is already being used for its intended purpose.

This is a powerful example of functional fixedness. Once we associate an object with a specific task, we tend to overlook other uses for it.

Overcoming functional fixedness opens up many possible solutions, and one SIT thinking tool for addressing it is task unification.

- Task Unification: the assignment of new tasks to an existing resource

When we discuss the scenario about a flat tire, you would not believe the solutions that are proposed before someone suggests using the jack to loosen the bolt. People will call a towing service like AAA or suggest hitching a ride from a stranger. But we are here to think creatively and innovatively. While those other solutions may work, their complexity compared to simply using the jack proves that innovation sometimes occurs when we limit our thinking to what is in front of us. This leads us to the first SIT thinking tool in the creative matrix, which is task unification. Task unification involves assigning a task to an existing resource. This process forces you to reflect on your functional fixedness.

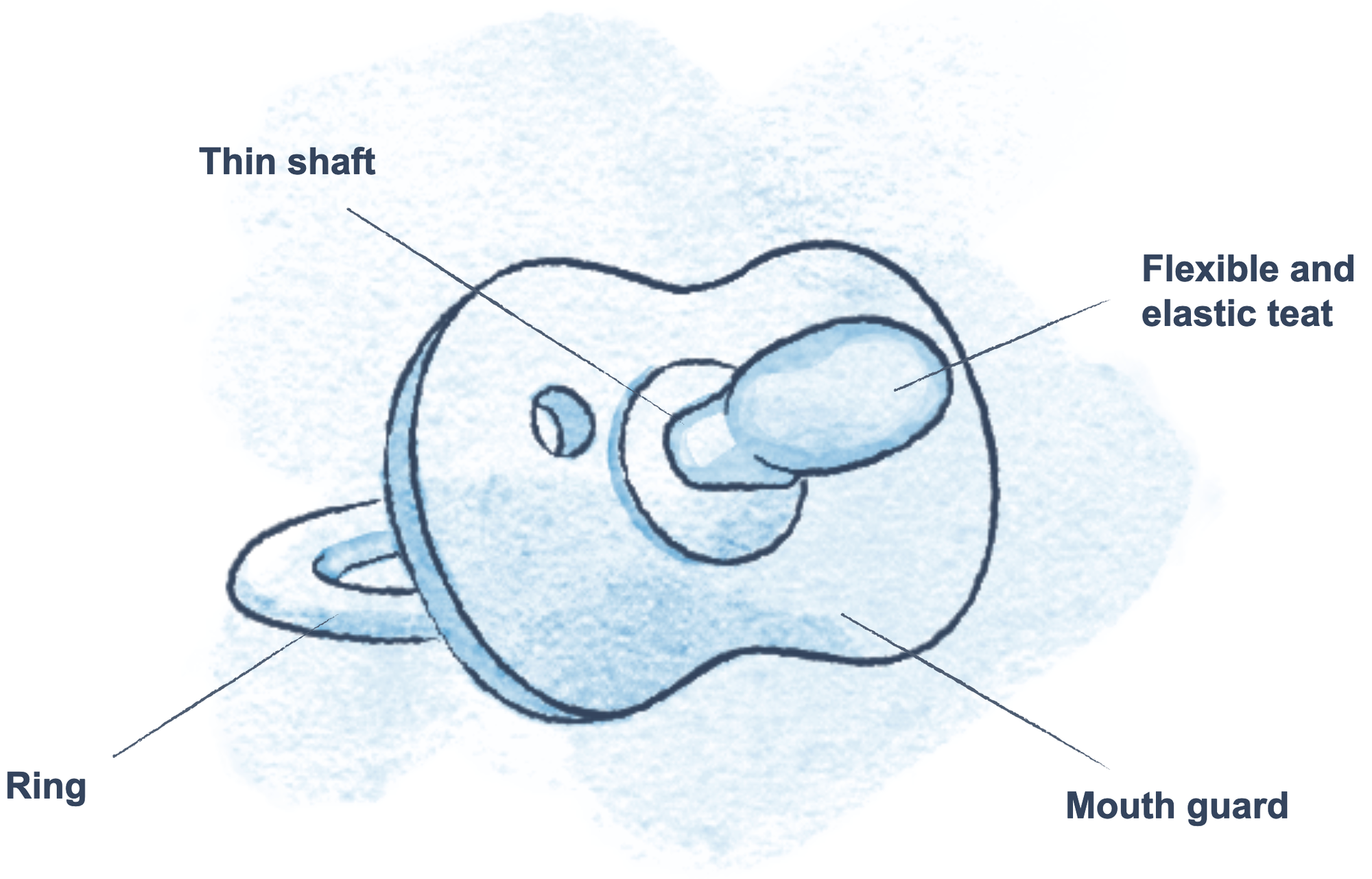

Let's take a look at some examples of this common and extremely useful tool. A vehicle like a bus, van, or taxi can be used as an advertising medium. This example has been around for many years. The existing resource was the vehicle, which was given the additional task of displaying messages for people outside the vehicle. The side of the bus became both a structural feature and a billboard. There is also the example of Uber. The creators of Uber took existing resources, other people's personal vehicles, and assigned them the additional task of transporting customers for a fee. The Uber app allowed users to switch between these tasks for their cars.

Or let's consider a service example. Do you remember the days of long lines to check in at the airport? Now we use our phones to check ourselves in and to board the plane. Smartphones have opened up numerous possibilities for task unification. So we see it everywhere in the world around us.

We tend to think of innovation as an outward expansion of what is possible, but creativity frequently occurs within limitations. If we are restricted, we have to find original ways to use what we have.

Task unification and other SIT thinking tools reflect the SIT principle called the Closed World, which suggests we should solve problems by considering how to use the resources that already exist in an environment or situation.

One of the basic principles of the SIT method is the closed world principle. The closed world principle dictates that when you're looking for an innovative solution, or you're looking to create new product value, the only resources you're allowed to use are those resources that you already have available to yourself. And oftentimes, that sounds quite counterintuitive because in the world of creativity and innovation, we're constantly taught to think outside the box and think beyond what you have right now. And that's probably because there's a natural tendency of people to believe that if they already have the solution under their noses, they would have seen it long ago. And therefore, if they are embedded in a tough problem, or they can't think of what their next-generation product is going to be, it's probably because they don't have the resources right now to do it. So they have to look externally to bring in completely new resources in order to make that happen. That's a fallacy, actually, in the world of innovation.

What the research shows and what we find time and time again is that you really have many more resources than you originally thought. When you're too focused on listening to the voice of the customer, and you're getting inputs only externally, you try to find solutions externally also. And t's very hard to be introspective about what you already have in order to provide more value.

Therefore, with a closed world, whenever we start applying a tool, the first thing we'll do is to build our closed world. A great term for the closed world is an inventory. When you're looking to start innovating, start with building an inventory. When you take inventory of the goods that you have in your warehouse, you don't decide in advance what's important and what's not important. You just make a checklist of everything that you have. That way, you know what you have in store, what you have in-house.

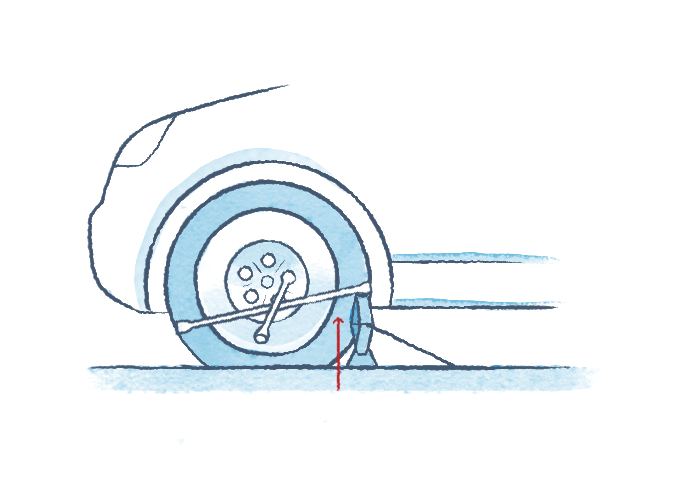

Let’s practice with task unification. A baby’s pacifier has three components: a nipple, a mouth guard, and a ring. These characteristics form the Closed World inventory of the pacifier.

Use task unification to think of another use for a baby’s pacifier. What is another task that these components could accomplish?

There are many possible answers to this prompt. One is taking the baby’s temperature. We could assign this new task to the rubber nipple, which was designed to soothe the baby. The component would complete both tasks, eliminating the need for a separate thermometer.

The following are additional examples of task unification that you may recognize:

- Guests can check themselves in at a restaurant using a kiosk. (The guests are the existing component - they now fulfill the task of a host. Anything in the product, service, or business model can be part of the inventory.)

- An eco-power faucet uses the water flowing through it to power a turbine and recharge the battery for its infrared sensor. (The water is the existing component - it now also generates power.)

- Crowdfunding platforms such as Kickstarter allow creators to assign fundraising and several related tasks (like social media marketing) to the customers who want a project to succeed.

The goal of task unification is not to force people to do more with less, or to offload difficult tasks onto users. Instead, it helps you identify underutilized components that might be used in additional ways. It is a powerful way to break functional fixedness and imagine components fulfilling a new role.

To put it simply, we too often overlook what’s right in front of us - like the jack holding up the car.

When you create an inventory of the closed world, you're basically making a list of components and objects. And when you apply the task unification tool, you're mentally converting a component into a resource. What happens in your brain is you're taking something, and you're deciding that now it's going to become a resource for you, for whatever it is you've decided that you wanted to accomplish.

So in problem-solving, when you have a problem on one hand, and then you have a list of elements that you tell yourself, I now have to go through this list and figure out how the elements can solve the problem - and not just in general what can a solution to the problem be - it's a much easier mental and cognitive process because it's more of a matching process. Here's a problem. Here's a possible solution. Let's figure out how to match the possible solution to the problem, rather than saying, here's a problem, now anything's possible. Think of a potential solution. And you don't even know where to start. And that's one of the strengths of the SIT methodology. You're never starting from a blank page. You always have your inventory in front of you. You always have your list of resources. You always have your closed world that you're looking at. So you're never stuck.

Think of an existing smartphone application. It might be one you use daily, or simply one you know about. Ride-sharing apps, email apps, and mobile games are all possibilities.

Now, assign a new task to the phone’s camera within that application. Do not think about the market or other limitations. Just focus on an idea that might be novel and useful. Explain your idea and why it might have value.

Task unification is not limited to products and physical resources. It is equally applicable to services, business models, strategies, and other innovations.

For example, someone’s car or spare room is an existing resource. By assigning these components, a task typically performed by a traditional business - taxis and hotels, respectively - Uber and Airbnb created disruptive new models.

This type of innovative thinking extended to further task unification at the level of strategy: Uber did not stop with its new contractor business model for ride-sharing. Once the new business model had proven to be a success, they assigned another task of meal delivery through Uber Eats.

The Principle of Function Follows Form

Let's define Function Follows Form (FFF) and explain how it makes innovation ideas stronger.

Again - think of an existing smartphone application. It might be one you use daily, or simply one you know about. Ride-sharing apps, email apps, and mobile games are all possibilities. Now, assign a new task to the phone’s camera within that application. Do not think about the market or other limitations. Just focus on an idea that might be novel and useful. Explain your idea and why it might have value.

Reflect on your response to this prompt. Now that you have a “virtual product,” what do you think the challenges around marketability and feasibility might be?

The activity above asked you to reflect on marketability and feasibility. You may have many theories on why your design is marketable to the target audience and what challenges you might face. What I would like you to focus on now is the order in which you completed this multistep activity. I first asked you to come up with an idea without considering its marketability or feasibility. You only considered these things after generating the idea. They were two separate steps, and this was intentional.

This is the basis of another key SIT principle called Function Follows Form. Some of you may be familiar with an architectural principle that suggests the reverse, called Form Follows Function. In other words, the design of a building or object should reflect what its function is. That's usually the way people think. However, when solving innovation problems, we must focus on breaking the fixedness of traditional thought patterns. Therefore, the SIT principle turns this thinking on its head.

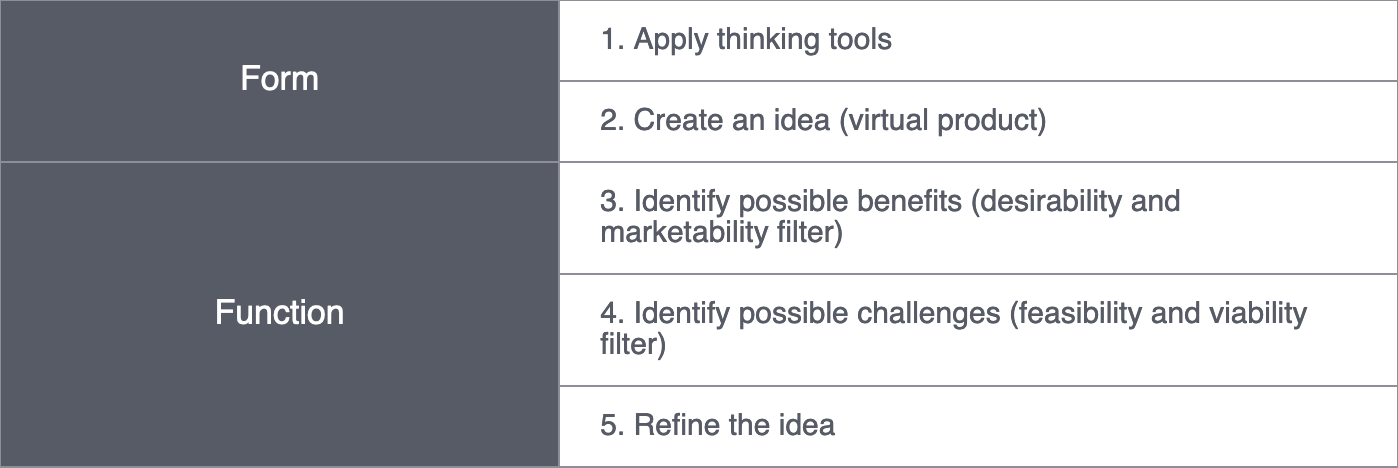

You use the creative matrix to develop ideas first, and you wonder about their function, including their marketability and feasibility, later. In the closed world, we start with an existing situation, our inventory of characteristics and attributes. We then apply the SIT thinking tools to manipulate these attributes, as with task unification. This creates a virtual product, which is our form. Then, and only then, do we move on to explore the idea's potential benefits, or its function.

This approach may seem counterintuitive. After researching user needs in the clarify stage, why shouldn't we keep marketing to users in mind as we ideate? We use Function Follows Form instead because research has shown that we are sometimes better at identifying the benefits of an existing form as opposed to creating a form with specific needs in mind.

As you apply the SIT thinking tools, focus on manipulating characteristics to create new forms first, then find a use for those forms that addresses the design principles.

Imagine a plastic food container that comes with a smaller salad-dressing container inside of it. The smaller container snaps into the lid on the inside. The result is one container with two compartments, so that the salad and the dressing remain separate.

This is an example of task unification: the lid also serves as a container for dressing, in addition to covering the contents.

To practice with the Function Follows Form principle, first identify the possible benefits of this idea. Then, consider the possible challenges of any kind - desirability, feasibility, or viability.

To address the benefits first, we can point out the convenience and minimal space requirements compared to carrying two separate containers. There might be a strong market for this idea among people who aspire to eat a healthier lunch at work.

Possible challenges include making the design easy to understand, and increased customer frustration if the dressing lid fails and makes a mess. Will users easily understand the benefits and how to use it?

A critical element of the Function Follows Form principle is considering the benefits first:

- Whenever you generate new ideas, it is natural to consider why they won’t work. Instead of discussing challenges directly, consider potential benefits first so that you approach ideas in a more balanced way.

- This advice encourages divergent thinking: expanding possibilities and generating as many ideas as possible.

In addition, by breaking cognitive fixedness and generating a novel idea first, and then considering useful applications later, you lower the cognitive load of ideation. You consider the positives, refine the idea by considering the negatives, and then use what you have learned to diverge and explore other ideas.

Let's discuss the value of going back and forth between form and function as you develop ideas.

When we start a project, we first want to scope and understand what's the goal of our innovation. Remember, innovation is thinking and acting differently to achieve your goals. So we want to create the framework around our goals to make sure that we're very clear about what we want to accomplish. We understand enough about the market and what the voice of the customer is asking us for. We go to the other side of the pendulum, and we start a process of function follows form. We started by taking our closed world elements, we applied one of these tools. By applying the tools. we broke the fixedness. We came up with potentially something new, our virtual situation. Now we have to go back to that first side of the pendulum and judge it and understand what the value could be? We're going back to our convergence, what's the value for the market? What will the benefits be? What are some of the advantages of this potentially fixing this broken system over the existing system right now? If we find benefits, if we understand what the value can be, then we also have to ask questions and judge that around feasibility. How can we actually make that happen? How can we accomplish that? And that's another type of converging thinking. Once we have that converging thinking, inevitably challenges come up because if it's new and different, if it's truly new and different, it won't be simple to implement.

And so now you've identified problems. In order to solve problems, you have to diverge again, which is why in the next stage of the function follows form we create adaptation by problem-solving using these same fixedness breaking tools. And so it's constantly an interplay between the divergence and the convergence that leads to, at the end of this process of function follows form, we end up with an idea. Now an idea, one idea, is almost never going to be the best solution, or one idea is never going to be the place where you want to stop. Because, of course, there can be more ideas, and oftentimes your first idea isn't your best idea.

Let’s explore an earlier example further - that of Airbnb. The Airbnb model is based on task unification. The founders created a model that would assign a person with a spare room the new task of serving as a part-time innkeeper.

Imagine you had come up with this idea and needed to apply the Function Follows Form principle to it. The time limit will encourage you to record your initial impressions.

From the traveler’s perspective, what would you define as the main benefits and challenges for the initial idea of renting out an air mattress in someone’s apartment?

The initial market identified for the Airbnb business model was people traveling to cities when traditional lodging establishments like hotels would be fully booked. The advantages were:

- It provided a place to stay when other options were unavailable.

- It was less expensive than traditional options.

Challenges included:

- Would people pay for a room in a private residence?

- Would they feel safe, and would they trust the payment method?

It was simpler to incrementally change and adapt the idea of “rent an air mattress” to respond to these benefits and challenges than to come up with a whole new solution from scratch.

The following table summarizes how the SIT thinking tools and Function Follows Form can create a structured process for generating and revising ideas:

After you have refined the idea, mark it under each matching design principle in the creative matrix. As you practice innovation, you will move through this cycle many times. Keep in mind that the filters are used here to refine ideas, not to evaluate whether they are worth recording for discussion later.

If you start discarding ideas now, you may miss important connections and the opportunity to combine them with other ideas later. You will explore numerous tools for rigorously evaluating ideas and combining them in the develop phase later.

Now that you know the steps in the SIT methodology, and the principles behind them, let’s explore the rest of the thinking tools in the next article!