The Status-Quo Bias

Implement: Communicate and Structure for Success - Overcoming Developer and User Bias

Learning Objectives:

- Explain the gap between users’ and developers’ perspectives on innovation

- Analyze the difficulty of communicating an innovation’s value to different stakeholders

The following are all reasons why an innovation might face resistance among internal stakeholders. Which one do you feel is the most difficult to overcome?

- Cost of development

- Comfort with existing processes

- Misunderstanding due to lack of previous models

- Pressure to meet short-term goals

- Risk of facing new competitors

Regardless of which challenge you find the most difficult, they have a common theme: Internal stakeholders preferring the status quo. Existing goals, budgets, and expectations around risk are the top priority in the “operational world”.

The status-quo bias, originally defined by economists William Samuelson and Richard Zeckhauser, is important because innovators have a preference against the status quo. They are often working against the expectations and preferences of others in the organization, and even of potential users.

Many innovations are gradual improvements to existing products, services, models, or strategies. Others truly change their market because they are major breakthroughs. But even when these fully tested and developed innovations respond profoundly to user needs, many challenges to success remain.

One of the greatest challenges to overcome is the status-quo bias. People are naturally biased against change, unless it has a clear benefit. And while these benefits may be clear to you, remember the curse of knowledge - your users may not see them.

The key mistake in the implement phase is believing that users and external stakeholders are even neutral to your innovation. In fact, there are three views to consider:

- The developer's view, which is based on the innovation's economic utility.

- Then there is the neutral view, someone who could be swayed, but has no attachment to either side.

- Finally, there is the view of users, stakeholders, and customers.

These people start with their own perceived utility of your innovation, based on the status quo. Their background, pain points, and experiences with existing offerings in the market all prejudice them against your innovation. The goal is to understand that the first step may not be winning them over to your viewpoint, but even getting them to a neutral point of view.

Because of their status-quo bias, users and customers will overestimate the costs of the innovation. Any sacrifice, such as higher financial cost or time required, will be magnified because of the bias toward the status quo. They will also underestimate the benefits of the innovation. You may understand how superior your innovation is, but to a user considering it from a fresh perspective, the benefits will need even more promotion than you assume.

If you do not consider the status-quo bias as you begin to communicate the value of your innovation, you may create ineffective communications—or lose your focus on the value you were trying to create with your innovation in the first place.

Consider the example of Google Glass. The advantages and utility of the device, while clear to the company and its developers, were not clear to some audiences. For the consumer market, the perceived benefits did not outweigh the perceived costs in terms of price, privacy, and behavior change.

However, there was still value in the innovation, and Google found a user base for Glass in the business market rather than the consumer market:

- Using the screen in their glasses, warehouse workers can access instructions for complicated work processes in real time.

- They can also quickly take pictures to report or troubleshoot issues.

- As a result, many of the manufacturers that adopted the device reported significant reductions in production time.

This shows the importance of identifying different stakeholders and evaluating how difficult it would be to overcome status-quo bias and communicate value among different groups: In doing so, you may find an unexpected opportunity among a previously overlooked market.

Assessing Status-Quo Bias

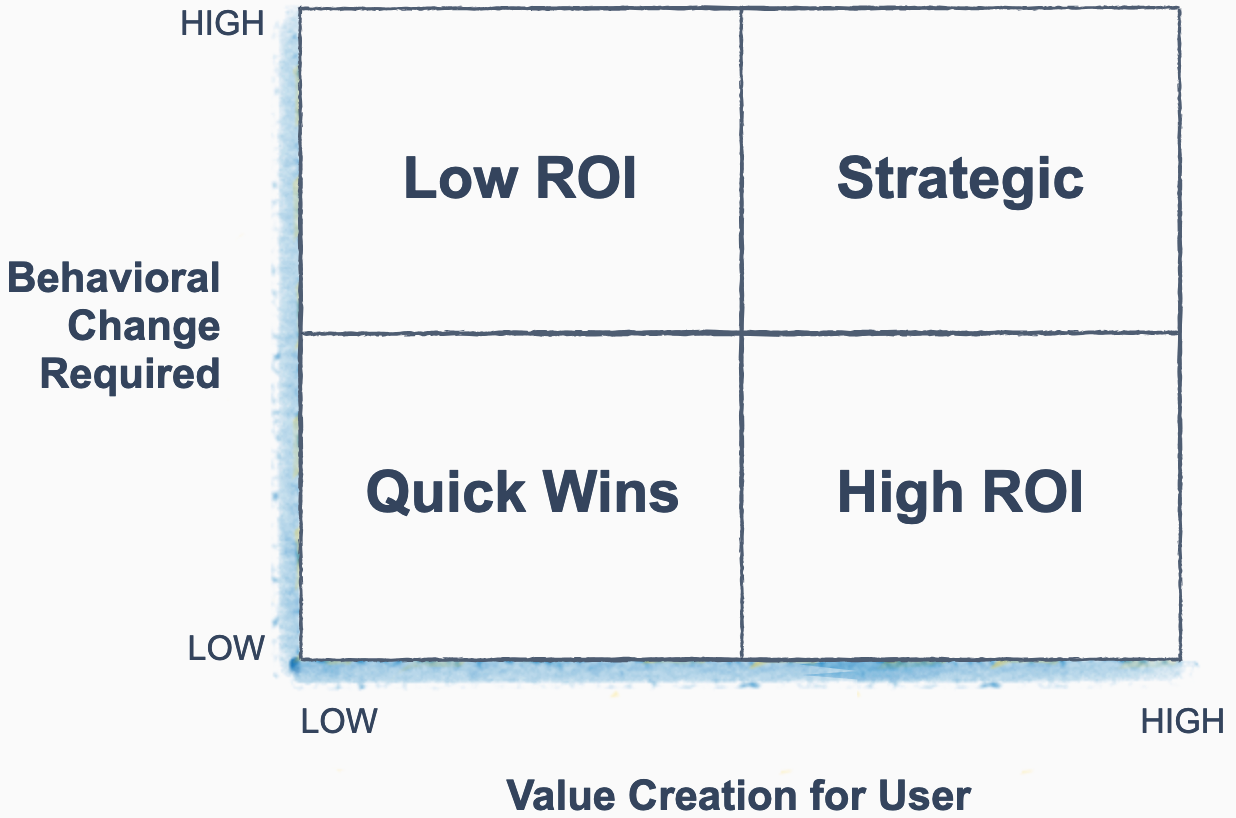

In 2006, HBS professor John Gourville described the psychology of new-product adoption as the tension between how much value the innovation creates (according to the user), and how much behavior change is required (again, according to the user).

If you graph John Gourville’s tension along the x and y axes, from low to high, you create four quadrants, as demonstrated in the following graph.

The resulting 2 by 2 framework has the same quadrants as the impact-difficulty matrix, which is not a coincidence—an innovation concept’s location in the impact-difficulty matrix also serves as a preview of the status-quo bias it will need to overcome. Let’s consider the qualities of innovations that fall within each of these quadrants.

- Quick Wins (Fewer perceived benefits, little behavior change required): Because these innovations require little behavior change, you can focus on bolstering the value they appear to provide.

- Example: New payment tiers for an existing telecommunication service—those who want less data can pay less, and vice versa.

- Low ROI (Fewer perceived benefits, great behavior change required): It is difficult to convince users to overcome their skepticism.

- Example: The Segway, a personal transporter on two wheels that was strikingly different from but had few perceived benefits over existing personal transportation options.

- High ROI (Many perceived benefits, little behavior change required): As with Quick Wins, little behavior change is required, so you can focus on the innovation’s exceptional functional and emotional benefits.

- Example: Google’s search engine didn’t have complex categories or other systems to learn and adapt to—but the benefits of the uncurated browsing experience were enormous.

- Strategic (Many perceived benefits, great behavior change required): These innovations require a careful communication strategy—one that minimizes costs and maximizes perceived value.

- Example: The iPod would fundamentally change users’ relationship with physical media. Would they give it all up for an expensive device? As you will soon learn, Apple focused on latent pain points to make the innovation as appealing as possible.

Deciding where to place users in John Gourville’s 2 by 2 framework is important, as it has implications for how you can best design your communications strategy. Different user groups might be in different locations, and require a different approach.

Contrary to Google’s initial expectations, consumers were actually in the Low ROI quadrant. The value they perceived was low, and the behavior-change costs were high. But parts of the business market, like manufacturers, were in the Strategic quadrant. While still expensive and requiring new processes to implement—a great deal of behavior change—Google Glass also offered strong benefits to business customers in the form of increased productivity.

As in the earlier phases of design thinking, the key to communicating an innovation’s value is empathy for users and stakeholders. You must break free from the developer’s biased view of your innovation’s value. It may be helpful to return to the AEIOU tool from Clarify. Ask yourself: In the user’s environment and interactions, are there any hidden costs that you may need to overcome in your messaging? Remember:

- Users overestimate costs and underestimate benefits.

- Developers underestimate costs and overestimate benefits.