Budget Allocation

Allocating Budget and Measuring Success

Budget Allocation at Harvard Business School Online

Welcome to the final set of articles on Digital Marketing Strategy. It’s time to build on the skills you’ve gained so far by examining budget allocation and how to measure marketing success.

You will learn to:

- Understand how to measure the success of digital marketing campaigns.

- Explain why measuring successful marketing campaigns requires qualitative as well as quantitative analysis.

- Describe the limitations of return on investment as a metric and explain how attribution is an important consideration in measuring the success of digital marketing campaigns.

- Describe additional factors that organizations must account for when creating a digital marketing budget and explain their relevance.

- Understand customer lifetime value (LTV) and how it impacts marketing decisions.

- Differentiate between metrics that capture short-term vs. long-term marketing effectiveness, and explain the key considerations in calculating each of them.

- Apply your learning by allocating a digital marketing budget for an organization.

Let’s introduce the first case that we will be examining.

We discussed digital marketing strategies that you can use to acquire, engage, and retain customers. These strategies require significant investment, and companies need to ensure that their marketing strategy has been successful for the bottom line of the business. This requires the use of quantitative metrics, as well as qualitative judgment.

We'll return to some of the metrics commonly used to measure the effectiveness of marketing campaigns, such as ROI and CAC. We will explore some additional metrics in depth, such as lifetime value. And then we will apply these concepts and concepts in a capstone case.

Let's begin with the critical issue of budget allocation. Budgets are finite. Managers need to allocate their budget towards the methods that are best suited to their goals. Measuring success and allocating budget are two sides of the same coin. To make wise budget allocation decisions, we must understand which efforts have been successful and which have not.

We will learn how you can make budget allocation decisions, what factors contribute to those decisions, and what metrics are most useful to inform them. The first case we will examine is from an organization - Harvard Business School Online. You may know HBS Online as a student, but we will take you behind the scenes to show you the origin of this program and the decisions HBS Online team made about whom to target and how to use digital marketing tools to reach them effectively.

We will learn from Simeen Mohsen, senior managing director of HBS Online, how the rapid growth of HBS Online affected her budget allocation decisions.

Meet Simeen Mohsen, Senior Managing Director of HBS Online. At the time of this interview, she ran the marketing and product management functions for the organization; she has since gone on to oversee the organization as a whole. Simeen describes how Harvard Business School started its online education initiative.

My name is Simeen Ali Mohsen. And I'm the managing director of marketing and product management for Harvard Business School Online. I've been in this role for about six years now and started my career after graduating from Stanford, went into management consulting for many years, and just fell in love with business in general, decided to go to business school, and went back into consulting and focused on consumer products and retail.

The story of the genesis of online education for Harvard Business School really starts with our prior dean, Dean Nohria. He was famous for his early statement. When he became dean in 2010, he made a statement that online education wouldn't be something that would happen in his era and wouldn't be something that Harvard Business School would be entering into.

From those early days, he was also involved in the work that was happening across the river with Harvard and MIT in terms of the work that they were doing collaboratively to build edX, an online learning platform, which was really one of the early MOOCs in the space, or Massive Online Courses. And so as he got to a little bit more about edX, he was really surprised by the level of interaction that participants were really having with each other in these online courses. Even if they were technical courses, he found that they were supporting each other and that there was a lot of peer and social learning that was happening.

And I think that really opened up his eyes towards possibilities for case-based education online. And I think that was the initial hesitation that he had was that Harvard Business School has such a distinct pedagogy in terms of its case-based approach. He wasn't sure that would work online. But hearing these experiences from these courses on edX and seeing that there was an opportunity to really collaborate and have the peer-to-peer learning, I think that's really what started his interest in pursuing online courses for Harvard Business School.

Simeen describes HBS Online’s process of finding the right match between product and target audience.

So initially, the thought was to try to serve the Harvard Business School students first, in terms of there was a particular program that students who were starting their MBA, who often came from very, very different backgrounds and experiences–there was an expectation that you would know certain concepts–certain analytics concepts, certain economics concepts, and certain accounting concepts–which would enable you to get the most out of your education.

So the three courses that were part of the initial program, which we called CORe, or the Credential of Readiness, were financial accounting, business analytics, and economics for managers. So the content in those three courses create the foundation of what is really expected–the MBA students to know coming into an MBA program.

So the initial audience in the early days was really to serve our Harvard Business School students. But pretty soon after the course was first launched, all of a sudden, we started getting interest in the early days from undergraduate students, from other working professionals who hadn't received this type of business education. So the shift came pretty early on in terms of just being focused on pre-MBA students to a much broader audience that ranged anywhere from college students to working professionals.

So our audience is split into three components today. So the first part is students who are what we call within the pre-MBA bucket, so either current college students or students who are applying to MBA programs after a few years of work experience. They're really looking to gain some business education from the perspective of learning those skills, but also demonstrating that they are investing in building those skills themselves.

The second part of our audience is working professionals, generally those in, I would say, the early to mid-stages of their careers. And a classic example there is perhaps a bench engineer who has risen through his company ranks by being very good at his job and then being asked to take on management of a team. And so that's a classic example of someone who is looking for just-in-time learning for some of these key business principles that they can apply to their job.

And the third component of our audience is entrepreneurs, people who are starting their businesses or thinking about starting businesses or perhaps entrepreneurs within their own organizations, who are looking to gain these really critical business skills that they can apply immediately.

Allocating Budget at Harvard Business School Online

HBS Online was launched in June 2014 with a three-course program. While substantial effort had gone into creating these courses, very little attention was given to marketing them because the team believed that “if we build it, they will come.” However, the team soon realized that it needed to do more. The inflection point in demand came a few years later when management decided to invest more into the digital marketing of these courses.

When the COVID-19 pandemic emerged in 2020, many online learning companies decided to pull back on spending. But as Simeen will explain, HBS Online saw this moment as an opportunity to capitalize on growth, which led the organization to double the size of its marketing budget.

So the early days of the pandemic were a huge time of growth for Harvard Business School Online. And I would say that was driven by three specific reasons.

The first was that as everything shifted in the early days of the pandemic from in-person to virtual, we already had an existing catalog of courses that were built for this medium.

The second part that we saw was, essentially, many people in our space overall, which is certificate, non-degree learning, really pulled back on their spending. And so at that time, we actually decided to double down. We doubled our digital marketing budget. We really saw the benefit of a hugely decreased customer acquisition cost. And we're able to see huge rates of traffic come in and convert. So we saw growth through that area as well.

And the third element, I would say, is that we decided to take modules from our existing courses and launch what we call free business lessons. We did this early, I think, April 2020. We were expecting maybe 5–10,000 people to log in and just experience these free business lessons. We had to shut down our system after 30,000 people... in the first six hours. And so that essentially brought a ton of traffic into our site as well.

So the combination of having the courses, doubling down, and spending more in this time when others were pulling back to take advantage of the lower CPCs out there, the lower rates, and then launching free business lessons, essentially took our traffic to 10x from pre-pandemic to post-pandemic.

The pressure was now on Simeen and her team to decide how to best allocate this substantially larger budget for the year 2021.

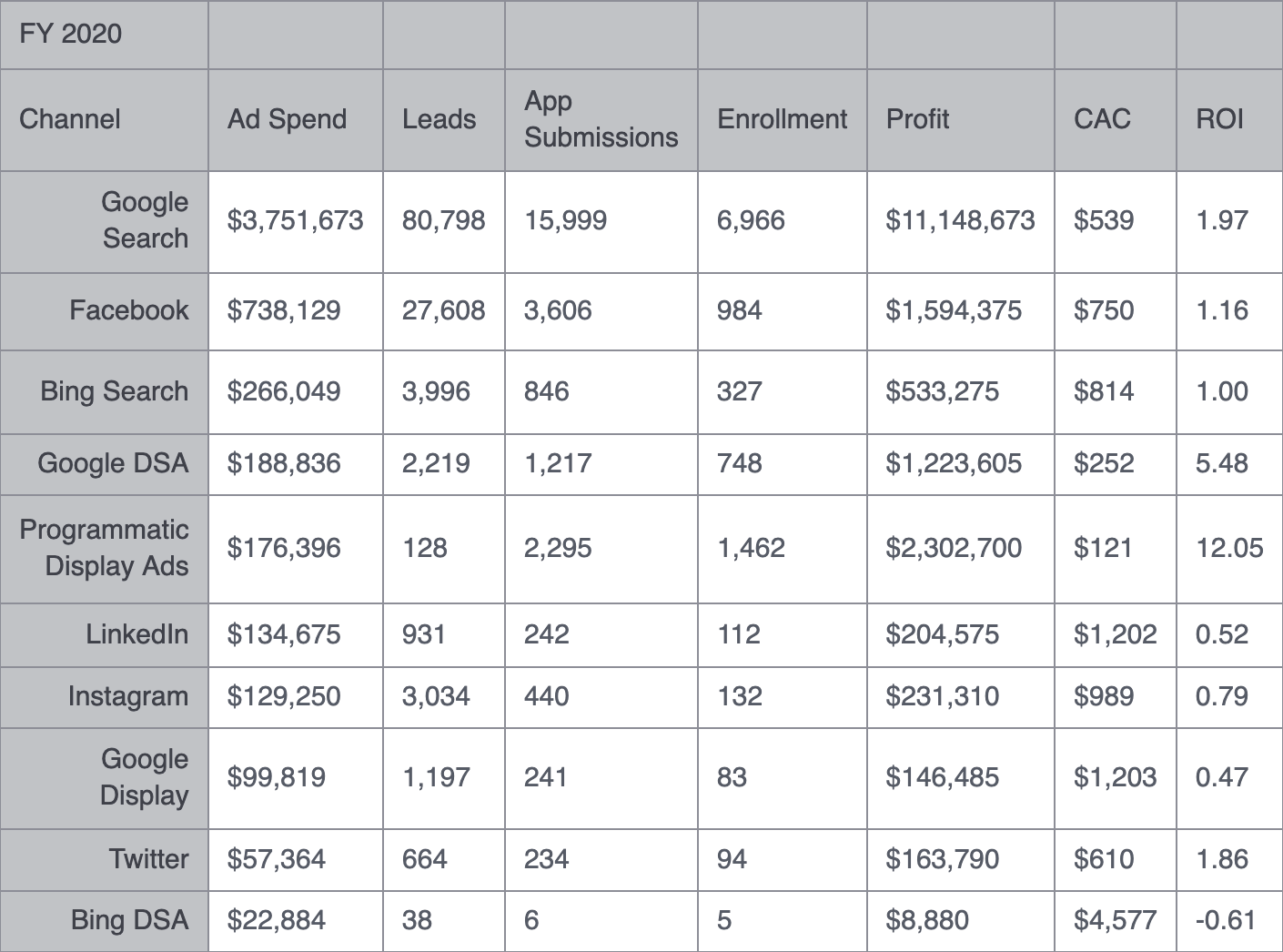

In order to make budget allocation decisions, let’s return to one of the first metrics we used: customer acquisition cost (CAC).

As a reminder, CAC measures how much a company spends to acquire new customers and can be calculated by dividing the total marketing spend by the number of new customers.

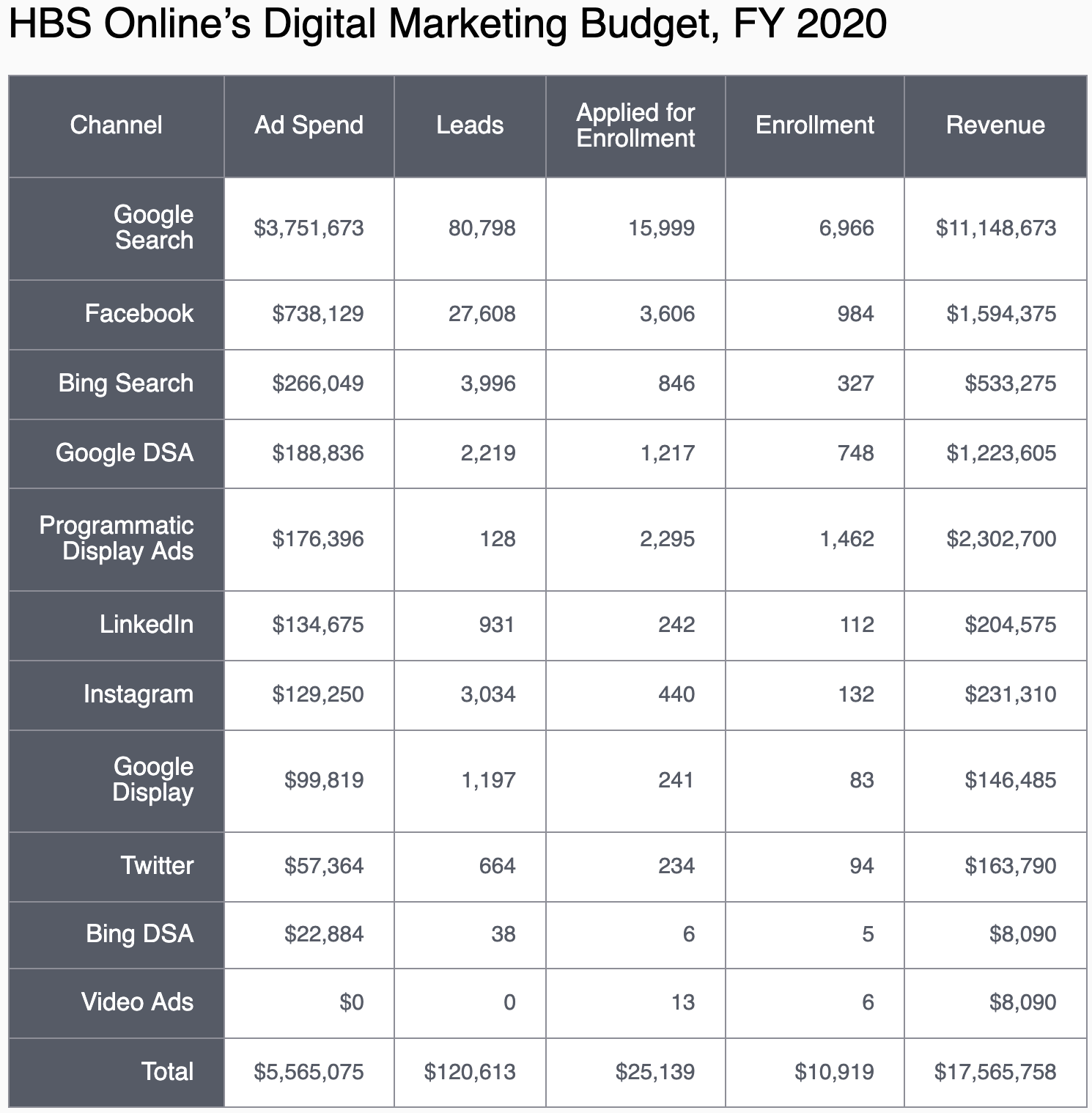

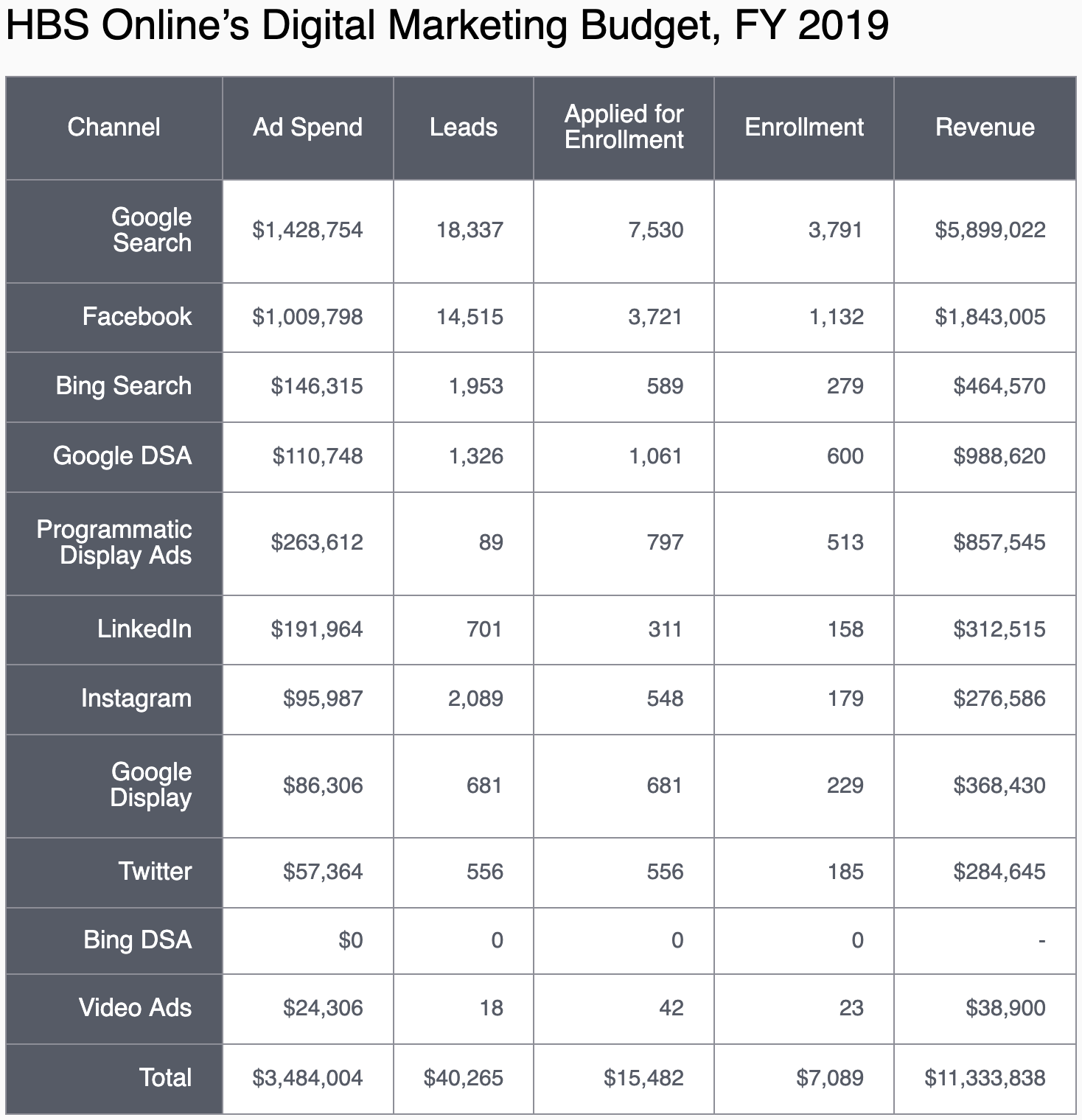

To begin the budget allocation process, Simeen and her team sat down to review their digital ad spend by channel over the last two years. A key task in budget allocation is measuring the success of recent marketing efforts.

Take a moment to examine the chart below, which lays out HBS Online’s digital ad spend by channel.

Please note that all numbers for this case have been disguised, but they capture the spirit of the debate that HBS Online was having at that time.

While CAC is a useful metric to decide where to allocate your resources, it fails to account for revenue generated. It is possible that the lowest CAC channel might be attracting customers to your low-priced products, or it might be attracting price sensitive customers to your site.

In other words, we should combine CAC with the profit generated through that channel to get the full picture of its return on investment. So even though Programmatic Display Ads and Google DSA are affordable channels for acquiring new customers, we need to combine their CAC with how much money it is bringing in to HBS Online to get a complete picture.

Recall that Return on Investment or ROI = (Profit – Ad Spend)/Ad Spend.

For HBS Online, as with most other online learning (as well as many other digital product providers), the marginal cost of an additional learner is small, so its revenue is almost equivalent to its profit. Therefore, in this case, we will use ROI = (Revenue – Ad Spend)/Ad Spend

Beyond CAC and ROI

Simeen explains the challenges that HBS Online faced as it began investing resources in paid media.

In the early days, I think there was an expectation that most of the budget would be spent on what I would call organic efforts, so content marketing, maybe a few sponsorships. But the expectation is because of the strength of the Harvard Business School brand that the online world would work in many ways similar to the offline world, where there's always been very significant demand for Harvard Business School education.

But in the online space, as soon as we entered into the space in the first year or so, it was very clear that the competition online was quite different. And you had to fight for mind space or mindshare in front of people who would potentially be interested in taking a course.

So the budget in the early days was really experimental to say here is a relatively small budget that we're going to invest in the paid marketing side of things, and then we'll look at the returns and see what the returns are like.

Simeen mentions the returns—that is, the ROI—of HBS Online’s paid media as one of the important metrics she was tracking as the HBS Online team made its foray into digital marketing.

Let’s now learn from Simeen about the other factors beyond ROI that the HBS Online team was tracking.

So an example for us here is LinkedIn, where the economics from our perspective on LinkedIn are very, very difficult. The cost of a lead, if you will, is pretty high relative to our other channels. But at the same time, it's important for us to be present in that channel because LinkedIn is a platform where people are looking to share their professional expertise and demonstrate their professional accomplishments.

So LinkedIn is a channel where we are relatively confident that the actual return doesn't necessarily reflect the benefit that we see from being on that channel. So it's by no means an exact science, but it is a general guideline that helps us determine where to shift our budgets or where to experiment.

The return, or the ROI, is a significant factor in the overall calculation. But other factors that go towards the calculation are, once again, making sure that we are reaching a variety of audiences. So we don't want to fall into that trap of only attracting the people we've attracted to date, which is, sometimes—happens in digital marketing. As you get more and more customers of a particular background, you build lookalike audiences, and that feeds upon itself.

So we really focus on making sure that we're building that awareness from a very early stage across a wide variety of audiences. Since our audiences are so broad, it's important to be able to invest in different channels so you're constantly finding new audiences. And the dynamics of each channel, the return on each channel, does change over time depending on the investment, the audience, and also the attractiveness of the particular offer to that audience at the time.

Although CAC and ROI are important metrics to guide your budget allocation, as Simeen described, several other factors should also be considered when allocating your marketing budget.

One factor is the potential volume that can be generated from a channel. Only a certain proportion of your target audience may be using a channel. And no matter how much you spend there, you are unlikely to increase volume after a certain point in time. For example, if you significantly increase your budget on paid search because of its high ROI, you may not get any new customers because you may have exhausted all potential customers who are actively searching for your product category. In the case of HBS Online, it might be better to go to channels that reach your target customers who are not actively searching, but might find your product relevant. Display ads or LinkedIn ads may be useful here, even if they have lower ROI than Google search.

Your budget allocation decision may also be guided by your desire to learn by experimentation. A company may not have figured out the best way to utilize a channel, even though it may be an appropriate channel for its target audience. Simeen mentioned that LinkedIn's relatively higher CAC and lower ROI does not discourage HBS Online from spending there because it's a place where many people may be looking to take online business courses. Perhaps HBS Online hasn’t yet figured out how best to leverage this channel.

The third factor is the quality of leads. Not all leads provide the same value to companies. Even at very low CAC, some customers are less valuable to companies. Perhaps they switch brands often, or they are very price sensitive and only buy at discounts. We will learn more about this later when we discuss customer lifetime value.

The fourth factor is the marginal cost, and not just the average cost of customer acquisition. As you spend more money on a channel, it gets harder and more expensive to attract customers. In other words, there are diminishing returns to scale and CAC increases as you spend more money on a channel.

n 2019, HBS Online spent about $1.43 million on Google search to attract 3,791 learners for an average CAC of $377. In 2020, it increased its ad spend for Google search to about $3.75 million that resulted in 6,966 learners for an average CAC of $539. Assume that the first $1.43 million spent in 2020 also generated 3,791 customers.

To calculate the additional CAC, you first need to determine HBS Online’s additional ad spend between 2019 and 2020. Using the ad spend figures given in the question, the additional ad spend would be $3,750,000 - $1,430,000 = $2,320,000. This additional ad spend resulted in the acquisition of 3,175 new learners. To get additional CAC, divide the additional ad spend by additional learners acquired: $2,320,000 / 3,175 = $731. Note that this amount is the marginal CAC, not the average CAC, which for 2020 is much lower at $539. This difference shows that the more you spend on a channel, the harder it becomes to acquire new customers.

Your budget allocation decisions should also consider how spending money on one channel might impact the effectiveness of another channel.

For example, a display ad might not immediately lead to purchase and, therefore, have low ROI. But this ad might generate interest among potential customers who later click on a search ad to buy the product. In this scenario, search ads should not get all the credit for sales. Part of the credit should go to the display ads that have moved customers down the marketing funnel.

But how do you assess the display ads' contribution to sales? This dilemma is known as the attribution problem. As you can imagine, understanding attribution is critical for making budget allocation decisions. In our example, if you do not account for attribution, you would overspend on search and underspend on display.

You might have noticed in the chart we showed you earlier that in 2020 programmatic display ads got only 128 leads but resulted in 1,462 enrollments. How is it possible to get more customers than leads? This happened because programmatic display ads are re-targeting leads that HBS Online got from other channels.

In other words, potential customers might have seen a search ad and visited HBS Online’s website or even provided them an email, but never applied for a course. Programmatic display ads re-targeted these potential customers. In this case, a lot of the credit for the effectiveness of programmatic display ads should go to search and other channels that generated leads in the first place.

Budget allocation requires managers to have a firm grasp on which of their marketing efforts have been successful in order to make informed decisions. Let’s take a moment to review all the factors Simeen and her team have to consider to measure their success and make budget allocation decisions for the future. They need to understand:

- CAC (customer acquisition cost): the average dollar amount that HBS Online pays to acquire one customer.

- ROI (return on investment): the ratio of ad dollars spent to profit (same as revenue in this case) generated.

- Variety of audience: ensuring that money budgeted towards marketing efforts brings in new potential customers.

- Volume of channel: how much potential business a channel can generate.

Experimentation and learning: testing and learning about new channels, even if they are not the most effective today. - Quality of lead: the long-run value of customers acquired through a channel.

- Goals: not limited to short-term sales, as a company might also want to increase awareness or have other long-term goals.

- Attribution: linking marketing efforts to the customers they acquired. We will learn about this factor next.

Did you have trouble narrowing the influence on your decision down to one answer?

It can be difficult to evaluate the role a particular ad played in the decision a consumer makes to purchase a product. The problem of attribution can be very complex. You can’t simply ask consumers what influenced their purchase because they have a hard time articulating it. But there are still methods that companies can use to help solve this problem.

Purchase Influence - as mentioned earlier, attribution is one of the biggest challenges in budget allocation. Without understanding attribution, you may give credit and allocate more budget to lower funnel channels such as search, even though middle or upper funnel channels such as display might have helped make search more effective. Now we will discuss attribution and the ways to assess it.

Attribution Models

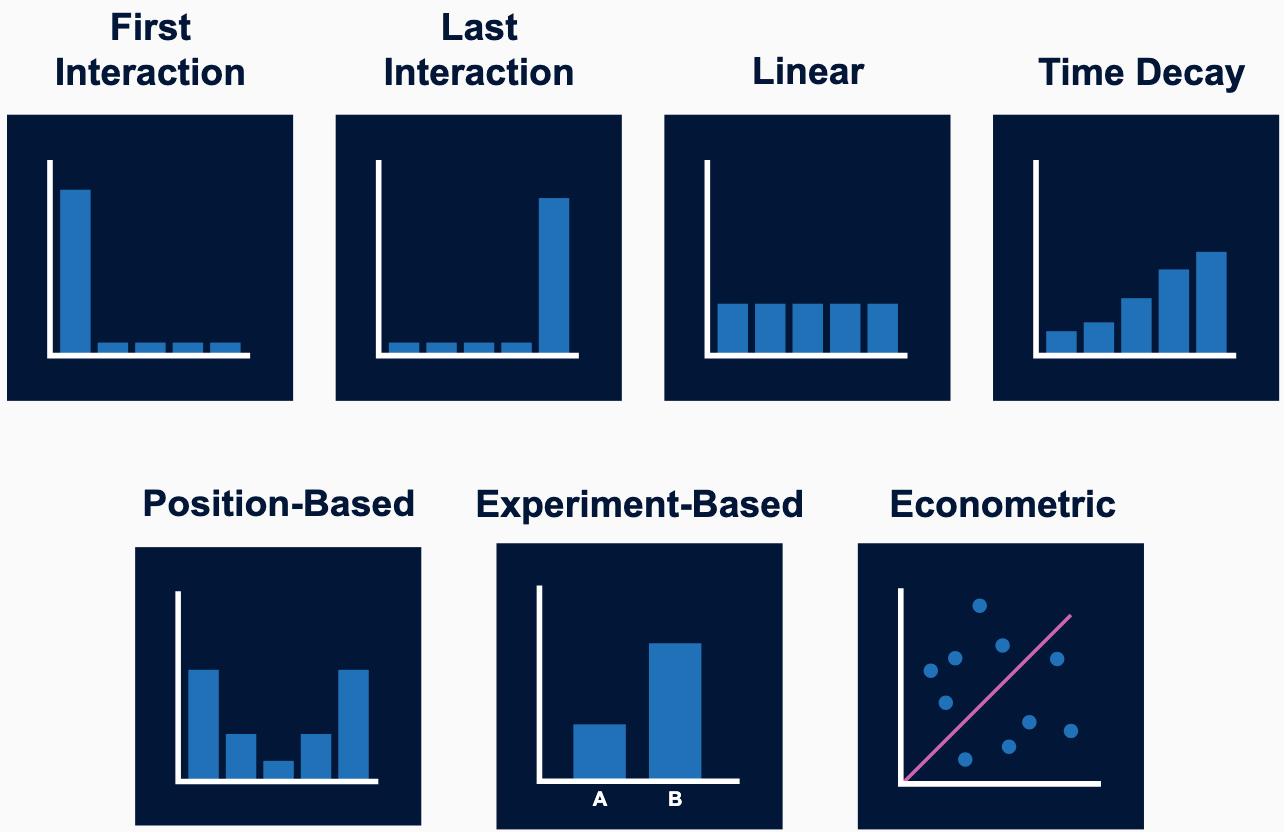

There are many methods that companies use to account for attribution. Here are a few common approaches.

Some companies use the first interaction, also called the "first touch" approach, that attributes 100% of the sale to the first ad the customer was exposed to. Others use the last interaction or the "last touch" method that gives 100% credit to the last ad that a customer saw or interacted with.

Some companies account for all the ads that customers may have seen by giving different weights to these ads. Linear attribution gives equal weight to all ads that a customer is exposed to. Time decay attribution gives more weight to recent ads seen by a customer. And finally, position-based attribution takes all ads into account but weighs the first and last ads higher.

All these methods are intuitive but ad hoc because they do not account for actual data or real consumer behavior. Some companies therefore use experiments or build econometric models using actual data to account for attribution.

In experiment-based attribution, companies use A/B testing to determine the role different ads play in generating revenue. For example, you can test the effectiveness of search ads with or without display ads by turning display ads on or off for some time.

The e-commerce site eBay carried out such an experiment. eBay wanted to know if the traffic to its site from paid search ads on Google would have come to the site anyway because eBay is a well-known company. To test this, the company switched off Google paid ads for several months and observed only a slight drop in its traffic and sales.

In addition to running experiments, companies can also create econometric models that capture the effects of various ads on consumer behavior. This is similar to running a regression with multiple variables to find the marginal effect of each variable.

At HBS Online, Simeen and her team opted to create a last-touch model for tracking attribution. She notes that no model will create a perfectly exact representation of attribution; rather, attribution is valuable for measuring relative rather than exact performance.

So attribution, at the highest level, is understanding the return on investment from each marketing channel. If it were to be done very cleanly, you would say, I have $100 that I'm investing in display ads, and I'm driving 100 customers from that.

Now, things in reality are not very clean. And attribution is one of those things that's hotly debated, whether you do last-touch attribution—so what was the last message that your consumer got before they decided to convert on your website—or first-touch attribution—so on the flip side, what was the first message that they received or the first ad that they saw?

And so there are many, many different models of attribution and many approaches towards attribution. Our philosophy has always been that we are consistent in our approach. So we developed a last-touch attribution model. Our thought is that it's a great way to measure relative performance rather than exact performance.

So anybody who tells you that your attribution model is giving you the exact return is not being fully truthful.

The other factor that's changed in the last few years is that attribution has become more difficult as more privacy controls have been put in place. It's hard to track the exact actions that a user is taking across the entire chain until they get to your site.

So attribution is quite difficult. But we use that more as a guideline than as an exact science.

So in general, we'll say we know that display generates roughly this much return. But there's a halo effect from being seen on certain channels that we try to divide across the multiple channels.

Course Spillover: Complications to Attribution

Take a moment to download and review this chart of HBS Online’s ROI of digital spend by course. Note that this data has been disguised for use in this course.

One of HBS Online’s most popular offerings is the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program, which provides foundational knowledge in Business Analytics, Economics for Managers, and Financial Accounting.

The following chart shows the courses that learners enrolled in, organized by their original paid media click source. Note the presence of “crossover” here, where paid media for one course results in an enrollment in another. For example, 101 people clicked on the ad for a finance course but enrolled in CORe (second column, fourth row of data).

Recall that ROI = (Profit – Ad Spend)/Ad Spend. In general, you would use profit instead of revenue in ROI calculations, but for HBS Online, the variable cost of adding one more learner to a course is negligible, so we are assuming that revenue is almost the same as profit.

To calculate ROI for a specific course after considering course crossover, you will need to account for all the revenue that a course’s marketing has generated—not only from enrollment in that specific course itself, but also from enrollment in other courses. In this way, you will account for revenue from a customer that may have clicked on an ad for, say, Entrepreneurship, but ended up enrolling in Negotiation.

Now that you’ve considered your strategy for factoring in course crossover, you will calculate ROI for CORe while accounting for course crossover.

For this calculation, you will need data from the HBS Course Crossover spreadsheet file download, as well as the following:

- HBS Online ad spend on CORe: $521,368 (FY 2020)

- Price of enrollment for CORe: $2250

- Price of enrollment for other courses: $1600

- ROI formula: ROI = (Profit – Ad Spend) / Ad Spend

Hint: To calculate the ROI for CORe, start by determining the total revenue generated from marketing for CORe.

To arrive at the ROI for CORe, we need to start with the data on the course crossover chart. We know that the total number of people clicked on an ad for CORe = 1,268 (last column, third row in the chart) and that the total number of people who enrolled in CORe after clicking on an ad for CORe = 714 (second column, third row). This means that the remaining, or 1,268 – 714 = 554, clicked on the ad for CORe but enrolled in another course. In other words, CORe ads should get credit for enrolling 714 people in the CORe courses (at a price of $2,250 each), and 554 people in other courses (at a price of $1,600 each). Therefore, total revenue generated from CORe marketing = (714*$2250) + (554*$1600) = $2,492,900. HBS Online spent about $521,368 on CORe ads, so its ROI = ($2,492,900 - $521,368) / $521,368 = 3.78.

The CORe program is slightly different from other HBS Online course offerings, as it comprises multiple courses across a broad range of topics. Thus, CORe is likely to capture a larger and wider audience than some of the more specific courses, leading to higher ROI for HBS Online’s ad spend.

In an earlier chart (HBS Online Ad Spend spreadsheet download), we noted that HBS Online spent $1.491 million on branded ads.

Now you will use the data in the HBS Course Crossover spreadsheet download and the same approach that we used for CORe to calculate the ROI for branded ads.

Calculate the ROI for branded ads.

To calculate the ROI of branded ads, we first need to find the total revenue generated across all courses from branded ad clicks. The crossover chart shows that 3,913 students enrolled through clicks on branded ads (last column, second row). Of those, 774 were for CORe enrollment (second row, second column), with an average price of $2,250. The remaining 3,913 – 774 = 3,139 enrolled in other courses, with an average price of $1,600. So the total revenue from branded ads = (774*2250) + (3139*1600) = $6,763,900. We then find the ad spend on branded ads of $1.491m, and plug these numbers into our formula: ROI of branded ads = ($6.7639m - $1.491m) / 1.491m = 3.54.

Simeen explains how the expansion of HBS Online’s course catalog and course crossover affected the team’s decision about budget allocation.

The decision to spend behind specific courses has also changed over time. In the early days when I started with HBX, we had two courses. Now, we're up to about 18. And so when you're in a world where you've got two courses, it's a fairly easy decision. You invest in each of those courses, and you look at the return.

Now that we have so many courses, it's almost impossible to divide your budget that way. So we've taken a step back and we've looked at topic areas. So what we're doing is essentially talking about leadership and management or finance or strategy. And we're essentially promoting those topic areas across a variety of channels.

So when our future participants come to our site, they're looking at, essentially, content that leads them to one of many, many courses. And so overall, stepping back strategically, we're comfortable with that because we know that many people don't know exactly which course they want to take. And so we're comfortable with participants coming to us and going through that discovery process.

And we help them in that discovery process. We ask them what they're interested in. They'll tell us certain topic areas. We'll communicate with them via email, our social media, or through our community. And we encourage them to go through that discovery process.

At the end of the day, we do look at the number of enrollments that are generated from each of the channels by course. But for us, I think it's more important to look at the overall impact and the overall number of participants, rather than participants to a specific course.

So once again, we use that as a guideline. And we know that certain courses interacted well with each other. People who take Disruptive Strategy tend to take Strategy Execution. So we have years of data at this point that have enabled us to say, OK, these set of courses live together. And we're comfortable with that overlap or spillover effect that we see across courses.

But at a very high level, we allocate our budgets based on topic area. And then within that, we don't specifically assign a budget to the course. But that happens naturally based on the interest level of the people that we attract to the courses.

Attribution is a complex challenge that requires creative and proactive methods to measure. Course crossover created even more complexity for HBS Online, but the team eventually turned this complication into an asset by grouping courses by topic areas.

This grouping eventually resulted in the implementation of Learning Tracks, which enable individuals to complete three courses in a subject area to earn a Certificate of Specialization. These certificates signal to the marketplace and employers that a learner has invested in building a deeper, defined set of skills in a specific subject area.

Beyond Paid Media

Simeen highlights the challenge that low unaided awareness presented to HBS Online, and how it prompted investment beyond paid media strategies.

One of the things that we realized from the very beginning that the online space was very crowded. And so we did some research early on that showed that our unaided awareness for Harvard Business School Online, or HBX, at the time was really low. I think it was close to 4% versus some of our competitive institutions, like Stanford or Wharton, that had much higher awareness within those who were interested in gaining online business education.

So with that knowledge, we realized that we really had to be pretty widespread in terms of our reach and the goal of building awareness for our programs. And so looking at our approach to marketing overall, we developed strategies, both in terms of what we would call paid marketing strategies and non-paid organic strategies, as well, to make sure that we're reaching our audiences wherever they were getting information online, so everywhere from Google searches to content partners, where it made sense to have our display ads, to optimizing our own search engine search results, and content marketing, so really a broad kind of approach to find the types of learners that we were looking to attract, which were really motivated learners.

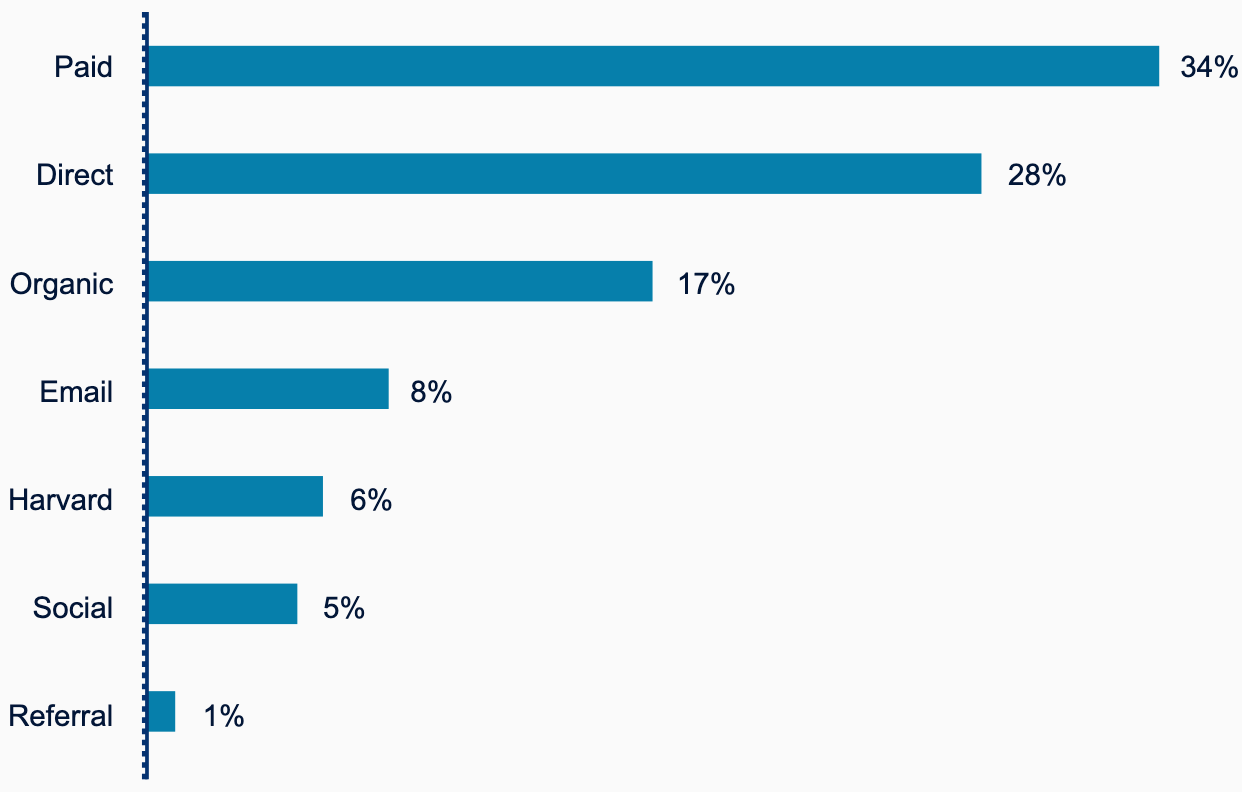

This graph describes the sources of traffic to HBS Online’s website in 2020. Notice that only 34% of the traffic came from paid media sources. As we’ve encountered previously, branded advertising has the highest ROI, likely due to the strong role that HBS Online’s association with the Harvard name plays in generating traffic and enrollments.

Simeen describes the important roles that search engine optimization and brand community have played in raising awareness of HBS Online brand and increasing engagement.

So search engine optimization is an area in which we've invested pretty heavily over the last three years. If I were to track back across my experience based over the last six years, I would say the first three years were focused on getting the paid media components up and running and getting to the returns that we wanted to get to.

Search engine optimization really started in the last three years, where we've started to invest in content marketing, invest in working with a firm that essentially started with the very basics, blocking and tackling, improving our website, improving our link, and really doing those things to focus on making sure that we are rising in organic search. And that's an area that requires constant work and constant vigilance, both on the fundamental mechanics of optimizing for search engines, essentially, and also on the content area, exploring new areas.

For example, video search has become a huge area in the last year or two. And so we've invested in that space, essentially, creating content pieces that we distribute through YouTube and other channels to be able to meet that demand on the video search side.

Our community is a huge component of both engagement with HBS Online, but word of mouth from additional people towards our courses. So we have a very robust community effort that really commences mostly when people are already in their courses. They're actively learning as part of their cohort. Once they earn their certificate, they're invited to join and participate in a broader community across all of Harvard Business School Online.

So someone will say, I've taken strategy execution. What is the next course I should take? And then people who've taken strategy execution will jump in and say, well, I took X, Y, and Z course afterwards. And so we find that our community is a great source of information for our future participants as well. And it enables the past participants to stay connected with each other and really benefit from some of those lifelong connections that are formed in other parts of the educational offerings at Harvard Business School, whether it's the MBA program, the doctoral program, or executive education.

One of the foundations– you leave these programs with a robust community of like-minded individuals that you can really rely on for the rest of your career. And HBS Online also replicates that experience through our community effort.

In 2021, Simeen and the HBS Online team continued with some of the successes of their digital marketing in 2020 while changing some other aspects.

The total marketing budget expanded significantly, with Google search (both branded and non-branded) and Facebook providing high ROI.

The marketing team decided not to focus very heavily on learning tracks in paid media, but learning tracks are promoted on the HBS Online website and often feature in marketing emails.

The team also utilized non-paid media channels, in particular blog posts and eBooks, to great success. They found that these non-paid efforts were the most effective ways to communicate with past participants.

The team continued to track several metrics closely. Number of leads and website traffic have been two important metrics to track how specific channels are impacting awareness. Enrollment yield is another metric that the HBS Online marketing team has been focused on as competition in the online education space continues to increase. This has led to a focus on high-quality leads and more emphasis on optimizing email in order to convert traffic.

Finally, the team has also been expanding its reach via targeted efforts in international markets in order to attract new customers.

You now have a better understanding of how HBX Online courses make decisions about marketing these offerings. Fundamentally, budget allocation is the process of directing resources towards your most effective marketing channels.

But as we have discussed, measuring success is a complicated process in which you must weigh many quantitative and qualitative factors. Quantitative factors include CAC and ROI. Clearly, the most cost-effective channels should get more resources. But as we saw, that is only part of the story.

You need to consider many other qualitative factors, such as the volume of leads from a channel, the diversity of consumers across channels, quality of leads, learning opportunities through experimentation, and attribution. We also took time to understand the attribution problem and ways to address it. It requires careful analysis of the customer journey and its various touchpoints.

While it is easier to map this journey for a fully online business, it is much harder to do it for an omnichannel business because it's difficult to know if an online ad led to a customer buying offline or vice versa. Attribution remains an area of ongoing research.

We also discussed the tradeoff between short-term revenue and long-term brand awareness and brand building, a topic we covered before, as well. We learned how efforts to increase brand awareness become more difficult to track using paid media metrics like CAC and ROI.

Finally, we learned that spending money on ads is not the only way for a business to grow. Owned and earned media are equally important to drive growth. However, it can be harder to make a case for investment in non-paid media strategies that target specific funnel friction points because these investments take longer to pay off and are more difficult to directly measure with metrics like ROI.

In our discussions of ROI so far, we have only examined a customer's immediate purchase. But we know that once we acquire customers, many of them will probably buy again. So their value is not limited to the revenue we get from their first purchase, but the stream of purchases in the future.

Next, we will examine a metric designed to measure these longer-term outcomes, customer lifetime value.