Dynamic Fit Management

Adapting strategy to market changes

Dynamic Fit Management refers to the ongoing process of ensuring that a business strategy remains aligned with the changing conditions and demands of its market environment. It involves continuously evaluating and adapting strategies to respond effectively to new challenges and opportunities. This concept is often emphasized in entrepreneurial settings, where businesses must be agile and responsive to survive and thrive in competitive and dynamic markets.

POCD elements can be assessed independently, but that real insight comes from trying to understand the relationship between them. This is the degree of fit between the elements.

Running a venture is like playing draw poker. You start with five cards. Obviously, you'd love the dealer to hand you a royal flush. An Ace, King, Queen, Jack, and 10 of spades. But that's a rare event. Fortunately, you can hand in some of your cards, and try to improve your hand. That's what entrepreneurs do. They start with some cards, and keep attempting to improve their hand. They get information, and then change the configuration of people, opportunity, context, and deal to increase the likelihood and magnitude of success while managing risk and avoiding failure.

Unlike poker, for which there are known probabilities and limited choices, entrepreneurship is unbounded, and highly uncertain. It's more like a sports team where you pick team members, a coach, support staff, owners, and location, and then you modify everything as the games, and season progress. The end goal, remember, is not to be the team with the best players, and coaches. The goal is to be the best team, the one that most consistently wins.

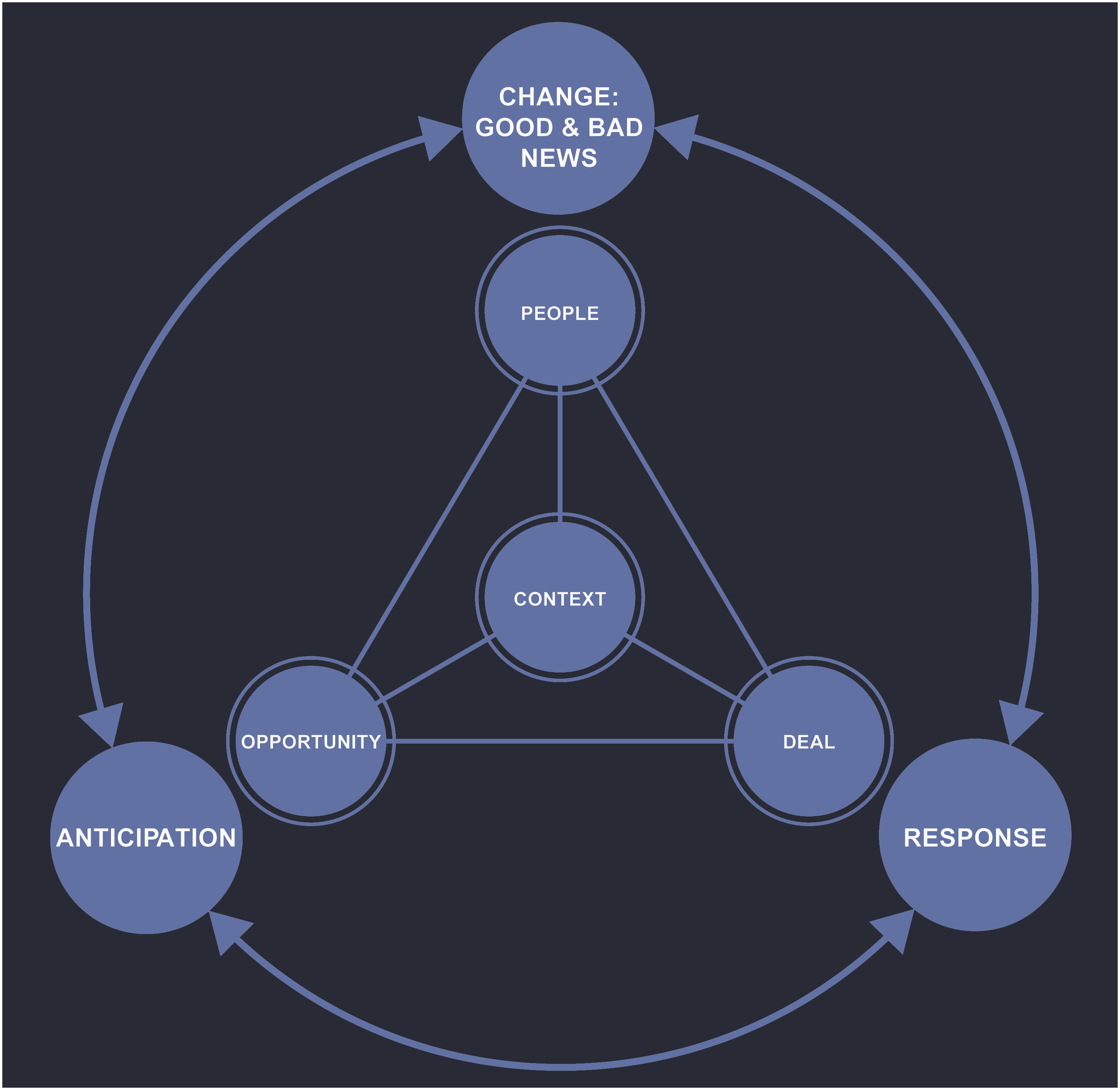

The process of changing P, O, C or D is dynamic fit management. At every point in the life of a venture, the goal is to get the right mix. Not that success is guaranteed if you do, but failure is a lot more likely if you don't. Because there's so much uncertainty, you must also make choices that anticipate what might happen in the future, whether positive, or negative.

We will explore how to use the POCD framework to build a high-value company that works for employees, customers, suppliers, and investors.

Anticipating and Responding to Change

We have discussed good news, bad news, and how entrepreneurial teams both prepare and respond to it. Entrepreneurial ventures are risky. Many things can and do go right or wrong, and management never has total control. So, how do you deal with uncertainty? How do you make up your mind when your decision may save your company or wreck it, and there’s no way to be sure which it will do? How do you deal with plain old luck, good and bad?

The best way, and perhaps the only rational way, to deal with uncertainty is to form hypotheses and run tests. Take a simple example. You are starting a new software venture. You have lots of experience in the industry and have identified a compelling solution to a big problem. You are technically trained, but you need to hire a Chief Technology Officer, or CTO, to develop the software and manage a team of engineers.

You find a great candidate, offer her a job, and give her 20% of the company stock, retaining 80% for yourself. But suppose that in three months you realize you have made a huge mistake, and you need to replace your CTO. That happens more often than you think.

If you did not have your CTO agree to a vesting schedule for her 20% share, that is, having the CTO earn the shares over time, you will have put your venture at risk. Now 20% of your company is owned by someone who isn’t doing anything for you - you’ve fired her - and she’s probably pretty angry. Not to mention that you have that much less stock to allocate to a new CTO or other new hires.

Similarly, if you have made a bad key hire, you are likely to need more time to test the market. If you only raised enough money to get to an alpha or beta version of your software, then you are guaranteed to run out of cash when the CTO fails to produce. Now you would need to raise money after messing up a critical team decision. That may still be possible if other elements of your venture are compelling enough, but it won’t be fun.

Every time you hire someone, you are running an experiment. You don’t know for certain that the person you hire will work out, but you have a hypothesis that they will, and you are running an experiment by hiring them. You must structure a deal that provides lots of upside for that CTO, but protects you and the company if she doesn’t work out. Moreover, a person joining your company is also running an experiment to learn more about you and your idea. They have a hypothesis that your business will work out and that they will be a good fit, but they don’t know that for certain. By agreeing to work for you, they are testing that hypothesis. If they agree to a vesting schedule - say, 20% of the stock vests after six months and the rest over the next 36 months - then they are demonstrating their belief in themselves.

So every decision made in a company must be made anticipating good news - hiring people who can make good news happen - and bad news - creating a cushion to cover mistakes or putting a stock vesting schedule in place. It’s like a decision to buy fire insurance on your house. You hope your house doesn’t burn down, and you work hard to protect it. But, if lightning strikes, you’ll have money to rebuild or buy a new house.

There are three simple questions that entrepreneurial managers can use to help anticipate changes and manage those possibilities:

- What can go wrong?

- What can go right?

- How can I manage the balance between risk and reward?

To summarize the model so far, we started with the basic idea that there are four elements of any venture - People, Opportunity, Context, and Deal. Each element is important - you always want excellence in each dimension. More importantly, you want the best combination of elements - the most experienced and capable people for a specific opportunity, the right financing strategy for the company, etc.

As venture managers complete tests and design new ones, they work to make what can go wrong less likely to occur, or if it occurs, less likely to cause failure. Simultaneously, they work to make what can go right more likely to occur.

The process of anticipating and responding to good and bad news is called Dynamic Fit Management, as illustrated in the diagram above.

Context and Dynamic Fit Management

Up to this point, we have focused on people, opportunities and deals, all of which management has some control over. However, there are many things which entrepreneurs cannot control but which can certainly impact the venture. Dynamic fit management is all about anticipating changes, preparing for them, recognizing them when they happen - way easier said than done - and reacting to them. Context is continually changing, which makes it a major part of dynamic fit management.

One major aspect of Context is the global macroeconomy, which affects the nature of opportunity, the capital markets, and the market for people. When the “Great Recession” of 2008 hit, many ventures failed, even when they had a compelling idea and outstanding people. Uncertainty was high, sales dropped, market values crashed, and investors deferred making commitments. No one really was prepared - or even could prepare - for such a difficult, extended recession.

One person’s crisis, however, is another person’s opportunity. In response to the turmoil in 2008, governments all over the world put in place new regulations that restricted major financial institutions. That opened up opportunities for other companies to offer services like small business loans or person-to-person loans, which were less constrained by the new regulations. Also, when asset values dropped, new entrants could buy things more cheaply, which lowered capital requirements and accelerated progress.

When the economy and capital markets are bad, starting and sustaining ventures is challenging. But it can also be a great time to launch a company. There will be fewer competitive entrants, and it may be much easier to recruit and retain talented people.

When the economy and stock market are booming, it may be easier to start, but harder to succeed. Many companies can get access to capital and chase the same idea. Typically, the experiments run during boom times are sloppier and run at a higher cost without a corresponding value improvement. Often, entrepreneurs get confused about how well their venture is doing with real customers. A high valuation does not guarantee a great final outcome.

We want to capitalize on contextual changes. One thing is certain - every entrepreneur has to consider the context today and remember that whatever it is, it isn’t going to stay that way.

In terms of Dynamic Fit Management, there are some lessons about how to think about the context. For example, your venture should be as robust as possible so it can endure changes in the environment. The economy has always been characterized by periods of growth and periodic recessions. You can’t assume that the stock market or venture capital market will keep going up just because it has in the past. It’s often a good idea to take advantage of a frothy market, raising money on attractive terms. But you should not spend that money as though prices will always be high, and you will always be able to get new capital.

At the same time, some of the great historic opportunities have come from changes in the context. For example, there are many ventures focused on products and services for an aging population. There are online and mobile platforms to help families and caregivers find each other and to help manage schedules and payments.

Risk and Reward Management

The act of deciding that will increase the likelihood and magnitude of success while managing the risk of disaster is risk and reward management.

It’s useful to think about risk and reward management by focusing on each element of the POCD framework.

Making Decisions for the Future

The famous hockey player, Wayne Gretzky, is reported to have said: “I skate to where the puck will be, not where it has been.” As it turns out, Gretzky probably didn’t really say that. But whoever did, makes a good point about entrepreneurship and dynamic fit management. You try to create the future you want. That is the essential goal in dynamic fit management - trying to get the right combination of people, opportunity, context, and deal that will position the company for the present and the future.

To get to the future, entrepreneurs form hypotheses and run tests. If you’re at Uber, you test UberX, then other variations on the theme. At Amazon.com, you try drone delivery.

Much of the literature on entrepreneurship focuses on finding product-market fit, certainly an important goal for all ventures. But to create a successful and enduring company, entrepreneurs need to do far more than just achieve product-market fit. They need a supportive financial and legal structure, great people in all roles, willing suppliers, physical plant and equipment, and more. We will explore how to make decisions that lead to better company outcomes.

Imagine that you have an idea for a new software program to help companies manage their indirect spending. As a financial analyst in the CFO’s office, you have observed your own company waste money because it allows many different department managers to order everything from water bottles to paper supplies.

You do some basic research and discover that many large companies do a poor job controlling these mundane kinds of purchases. But, if orders were aggregated across a company, then the cost of purchasing would decline significantly.

You sketch out a design for software that would be simple but effective to use and would exchange data with the central accounting software system. You recruit a friend who is a software engineer at the same company to work on the project. You both work nights and weekends together to sketch out a plan to create a company.

Now, let’s picture a desirable outcome: the idea works and in five years you have a large and successful software-as-a-service company with significant penetration of Fortune 1000 customers and plans for adding features. Other competitors have entered the market, but tough luck for them - you have already made yourself the leading firm. That’s the idea, anyway.

Think about this from the perspective of a founding team. As a founding team, what agreements must be put in place at the beginning to make it possible to achieve great success?

Several key issues come to mind from this simple discussion. One is that you and your friend must make sure that your current employers won’t have a legitimate claim to anything you invent while working for them.

Another is that you and your co-founder need to create a founders’ agreement. This would spell out key issues like equity splits, vesting, responsibilities, and contingencies if something bad happens or if circumstances change. Remember, you are running an experiment about whether you and your co-founder can co-exist and can do useful things at the venture. One founder may grow to dislike or mistrust the other. One might decide to take a job someplace else. Every founding team should establish a “startup prenup,” which allows all sides to talk frankly and plan at the beginning for the things that could go wrong later.

This “prenup” is something that you can do today, to make future decisions easier. Many companies find that decisions they make in the very early days affect the way they develop and grow far into the future.

Anyone who has seen the movie about the early days of Facebook, The Social Network, is aware that there can be real tensions and economic consequences when ventures get going. First, Mark Zuckerberg had allegedly agreed to work on a project with the famous Winklevoss twins. Instead, he created thefacebook.com, working with a few classmates, including Eduardo Saverin. The movie depicts a subsequent financing decision in which Saverin’s share of the company was heavily diluted. Saverin didn’t really understand his legal vulnerability and a new player, Sean Parker, and Zuckerberg decided to cut his stake. In the end, lawsuits and confidential settlements followed. No one needs to feel sorry for Saverin, though. His stake in Facebook is worth billions.

Every startup trying to go after a big market needs a lawyer. Early decisions about legal structure, tax planning, founders’ agreements, employment agreements, intellectual property, and plenty else have important consequences as the company grows. If you don’t pay attention and create a structure that supports growth, you will regret it. Bad decisions in the beginning can kill an otherwise promising company.

There are many situations in which bad financing decisions have disastrous consequences. For example, some entrepreneurs are so desperate to get money that they give a large share of the company to an early investor. But, that means that the founders may end up with a tiny share of the value pie if the company needs more capital. And, new potential investors may worry that the initial angel investor will control too much of the company.

Wrap-Up

The entrepreneurial journey is terrifying and exhilarating. Famed entrepreneur and venture capitalist, Reid Hoffman - he founded LinkedIn and is a partner of Greylock - describes it as leaping off a cliff and building an airplane as you fall. That’s a bit extreme, but it certainly captures the need to move decisively and adapt under pressure.

The argument is that entrepreneurship is a process designed to get to a desired outcome. We know what valuable, durable companies look like. Entrepreneurs form hypotheses about the end game and the steps to get there, and devise efficient and effective tests to reach major value inflection points.

Entrepreneurs know that there is risk and uncertainty. But they do not accept a particular level of risk as given. They keep making decisions to reduce their risk; that is, to minimize the probability that something will go wrong and to minimize how wrong it could go. Of course, at the same time, they keep trying to increase the likelihood and magnitude of success. They try to change the odds in their favor.

How do they do that? They pick the right people to execute on a compelling idea that offers sufficient value creation and capture potential to justify taking on the risk (the risk they keep attempting to reduce, but which they know they can never reduce to zero). They structure deals that attract, motivate, and retain the appropriate employees, investors, suppliers, and customers.

There are no guarantees. Ventures fail for many reasons, some internal and some external. When ventures fail, it doesn’t necessarily mean the people have failed. People only fail if they consistently make the wrong decisions.